Out of the Tar Pit

타르 구덩이에서 탈출하기

- 번역

- Abstract

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Complexity

- 3 Approaches to Understanding

- 4 Causes of Complexity

- 5 Classical approaches to managing complexity

- 6 Accidents and Essence

- 7 Recommended General Approach

- 8 The Relation Model

- 9 Functional Relational Programming

- 10 Example of an FRP system

- 11 Related Work

- 12 Conclusions

- References

- 주석

- 원문

- Out of the Tar Pit (PDF)

- Out of the Tar Pit (papers-we-love)

- Ben Moseley 와 Peter Marks의 2006년 2월 6일 논문.

번역

Abstract

초록

Complexity is the single major difficulty in the successful development of large-scale software systems. Following Brooks we distinguish accidental from essential difficulty, but disagree with his premise that most complexity remaining in contemporary systems is essential. We identify common causes of complexity and discuss general approaches which can be taken to eliminate them where they are accidental in nature. To make things more concrete we then give an outline for a potential complexity-minimizing approach based on functional programming and Codd’s relational model of data.

'복잡성'은 대규모 소프트웨어 시스템을 성공적으로 개발하는 데 있어 가장 큰 어려움입니다. 우리는 [[/people/fred-brooks]]{Brooks}가 제시한 우발적인 복잡성과 본질적인 복잡성을 구분하는 접근방법에는 동의하지만, 그가 주장하는 대로 현대 시스템에 남아있는 대부분의 복잡성이 본질적인 것이라는 주장에는 동의하지 않습니다. 우리는 복잡성의 주요 원인들을 파악하고, 그것들이 우연한 성격의 복잡성인 경우 제거할 수 있는 일반적인 접근 방식을 논의합니다. 그리고 더 구체적으로 설명하기 위해 함수형 프로그래밍과 Codd의 관계형 데이터 모델에 기반을 둔 복잡성을 최소화하는 잠재적인 접근법에 대한 개요를 제시합니다.

1 Introduction

1 서론

The "software crisis" was first identified in 1968 [NR69, p70] and in the intervening decades has deepened rather than abated. The biggest problem in the development and maintenance of large-scale software systems is complexity — large systems are hard to understand. We believe that the major contributor to this complexity in many systems is the handling of state and the burden that this adds when trying to analyse and reason about the system. Other closely related contributors are code volume, and explicit concern with the flow of control through the system.

"소프트웨어 위기"론은 1968년에 처음으로 등장했습니다. 그 이후 수십 년, 소프트웨어의 위기는 더 심각해졌으며 해결되지 못했습니다. 대규모 소프트웨어 시스템의 개발 및 유지 관리에서 가장 큰 문제는 복잡성입니다(시스템이 클수록 이해하기 어렵습니다). 우리는 많은 시스템에서 이 복잡성의 주요 원인이 '상태의 처리'와 이것이 시스템을 분석하고 이해하는 데 부과하는 부담이라고 믿습니다. 코드의 양과 시스템을 통한 제어 흐름에 대한 명확한 고려 등이 밀접하게 관련된 기여자들입니다.

The classical ways to approach the difficulty of state include object-oriented programming which tightly couples state together with related behaviour, and functional programming which — in its pure form — eschews state and side-effects all together. These approaches each suffer from various (and differing) problems when applied to traditional large-scale systems.

상태의 어려움에 접근하는 고전적인 방법은 주로 두 가지입니다. 하나는 상태를 관련된 동작과 밀접하게 결합시키는 객체지향 프로그래밍이고, 다른 하나는 순수한 형식을 통해 상태와 사이드 이펙트를 모두 배제하는 함수형 프로그래밍입니다.

이런 접근법들은 각각 전통적인 대규모 시스템에 적용할 때 각각 다양하고 서로 다른 문제들을 겪게 됩니다.

We argue that it is possible to take useful ideas from both and that — when combined with some ideas from the relational database world — this approach offers significant potential for simplifying the construction of large-scale software systems.

우리는 두 가지 접근법 모두 우리에게 유용한 아이디어를 제공해 주며, 관계형 데이터베이스의 일부 아이디어와 결합하면 이런 접근법이 대규모 소프트웨어 시스템 구축을 단순화하는 데 상당한 잠재력을 발휘하게 될 것이라고 생각합니다.

The paper is divided into two halves. In the first half we focus on complexity. In section 2 we look at complexity in general and justify our assertion that it is at the root of the crisis, then we look at how we currently attempt to understand systems in section 3. In section 4 we look at the causes of complexity (i.e. things which make understanding difficult) before discussing the classical approaches to managing these complexity causes in section 5. In section 6 we define what we mean by “accidental” and “essential” and then in section 7 we give recommendations for alternative ways of addressing the causes of complexity — with an emphasis on avoidance of the problems rather than coping with them.

In the second half of the paper we consider in more detail a possible approach that follows our recommended strategy. We start with a review of the relational model in section 8 and give an overview of the potential approach in section 9. In section 10 we give a brief example of how the approach might be used.

Finally we contrast our approach with others in section 11 and then give conclusions in section 12.

이 논문은 크게 두 부분으로 나눌 수 있습니다.

- 전반부는 복잡성에 초점을 맞춥니다.

- 제2장에서는 일반적인 복잡성을 살펴보고, 이것이 위기의 근본적인 원인이라는 주장을 정당화한 다음,

- 제3장에서 우리가 시스템을 이해하려고 시도하는 현재의 방법들을 살펴봅니다.

- 제4장에서는 복잡성의 원인(이해를 어렵게 만드는 것들)을 살펴본 다음,

- 제5장에서 이런 복잡성의 원인이 되는 것들을 관리하기 위한 고전적인 접근 방식을 논의합니다.

- 제6장에서는 "우발적인"과 "본질적인"이라는 용어를 정의한 다음,

- 제7장에서 복잡성의 원인을 해결하는 대안적인 접근 방식을 제시합니다. 이때, 문제를 해결하는 것보다는 문제를 피하는 것에 중점을 둡니다.

- 논문의 후반부에서는 우리가 권장하는 전략을 따르는 가능한 접근 방식을 더 자세히 살펴봅니다.

- 제8장에서는 관계형 모델에 대한 검토를 시작하고,

- 제9장에서 잠재적인 접근 방식에 대한 개요를 제시합니다.

- 제10장에서는 이런 접근 방식이 어떻게 사용될 수 있는지에 대한 간단한 예를 들어봅니다.

- 마지막으로, 제11장에서는 우리의 접근 방식을 다른 접근 방식과 대조하고,

- 제12장에서 결론을 내립니다.

2 Complexity

In his classic paper — "No Silver Bullet" Brooks[Bro86] identified four properties of software systems which make building software hard: Complexity, Conformity, Changeability and Invisibility. Of these we believe that Complexity is the only significant one — the others can either be classified as forms of complexity, or be seen as problematic solely because of the complexity in the system.

[[/people/fred-brooks]]{프레드 브룩스}는 그의 고전이 된 논문인 "은총알은 없다"에서 소프트웨어 구축을 어렵게 만드는 소프트웨어 시스템의 네 가지 특성을 규명했습니다. 그것은 바로 '복잡성', '적합성', '변경 가능성', '비가시성'입니다.

우리는 이들 중 복잡성만이 유일하게 중요하다고 생각하며, 다른 세 가지는 복잡성의 한 형태로 분류되거나, 시스템의 복잡성 때문에 문제가 되는 것으로 봅니다.

Complexity is the root cause of the vast majority of problems with software today. Unreliability, late delivery, lack of security — often even poor performance in large-scale systems can all be seen as deriving ultimately from unmanageable complexity. The primary status of complexity as the major cause of these other problems comes simply from the fact that being able to understand a system is a prerequisite for avoiding all of them, and of course it is this which complexity destroys.

복잡성은 오늘날 소프트웨어와 관련된 대부분의 문제의 근본 원인이라 할 수 있습니다. 불안정성, 지연된 일정, 부족한 보안, 심지어 대규모 시스템의 성능 저하까지 모두 따지고 보면 복잡성을 관리하기 어렵다는 것에서 비롯된 것으로 볼 수 있습니다.

복잡성이 이렇게 다른 다양한 문제들의 주요 원인이 되는 이유는, 단순히 시스템을 일단 이해할 수 있어야 모든 가능한 문제를 피해낼 수 있다는 사실에서 비롯되는 것입니다. 그리고 복잡성이 파괴하는 것은 바로 그러한 '시스템을 이해하는 능력'입니다.

The relevance of complexity is widely recognised. As Dijkstra said [Dij97, EWD1243]:

"…we have to keep it crisp, disentangled, and simple if we refuse to be crushed by the complexities of our own making…"

…and the Economist devoted a whole article to software complexity [Eco04] — noting that by some estimates software problems cost the American economy $59 billion annually.

복잡성의 중요성은 널리 인식된 것이기도 합니다. Dijkstra가 말한 바와 같이,

"만약 우리가 자신이 만든 복잡성에 짓눌리고 싶지 않다면, 우리는 그것을 선명하게, 엉키지 않게, 그리고 단순하게 유지해야 합니다."

…그리고 Economist지는 소프트웨어 복잡성을 주제로 전체 기사를 할애하기도 했는데, 해당 기사에서는 소프트웨어 문제로 미국 경제가 연간 약 590억 달러의 손실을 보고 있다는 추정값에 주목했습니다.

Being able to think and reason about our systems (particularly the effects of changes to those systems) is of crucial importance. The dangers of complexity and the importance of simplicity in this regard have also been a popular topic in ACM Turing award lectures. In his 1990 lecture Corbato said [Cor91]:

"The general problem with ambitious systems is complexity.", "…it is important to emphasize the value of simplicity and elegance, for complexity has a way of compounding difficulties"

시스템에 대해 생각하고, 특히 그 시스템에 변화가 생길 경우 그 영향에 대해 추론할 수 있는 능력은 매우 중요합니다. 복잡성이 얼마나 위험하고 단순함이 얼마나 중요한지는 ACM Turing award 강연에서도 인기 있는 주제였습니다. Corbato는 1990년 튜링상 수상 강연에서 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

- "야심차게 만든 시스템에서 일반적으로 발생하는 문제는 복잡성입니다."

- "…단순함과 우아함의 가치를 강조하는 것이 중요합니다. 왜냐하면 복잡성은 어려움을 복리적으로 증가시키는 경향이 있기 때문입니다."

In 1977 Backus [Bac78] talked about the "complexities and weaknesses" of traditional languages and noted:

"there is a desperate need for a powerful methodology to help us think about programs. … conventional languages create unnecessary confusion in the way we think about programs"

그리고 1997년, Backus도 튜링상 수상 강연에서 전통적인 언어들의 "복잡성과 약점"을 언급하며 다음과 같이 이야기했습니다.

"프로그램에 대해 생각하는 데 도움이 되는 강력한 방법론이 절실하게 필요합니다. … 기존의 언어들은 우리가 프로그램을 생각하는 방식에 오히려 불필요한 혼란을 일으킵니다."

Finally, in his Turing award speech in 1980 Hoare [Hoa81] observed:

"…there is one quality that cannot be purchased… — and that is reliability. The price of reliability is the pursuit of the utmost simplicity"

and

"I conclude that there are two ways of constructing a software design: One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies. The first method is far more difficult."

마지막으로, 1980년 튜링상 수상 강연에서 Hoare는 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

"…돈으로도 얻을 수 없는 하나의 품질이 있습니다… 그것은 신뢰성입니다. 신뢰성의 대가는 극도의 단순함을 추구하는 것입니다."

그리고

"나는 소프트웨어를 설계하는 방법에는 두 가지가 있다고 결론내렸습니다. 한 가지 방법은 결함이 없다는 것이 명백한 정도로 단순하게 만드는 것이고, 다른 한 가지 방법은 결함이 없다는 것이 명백한 정도로 복잡하게 만드는 것입니다. 그리고 첫 번째 방법이 훨씬 더 어렵습니다."

This is the unfortunate truth:

Simplicity is Hard

…but the purpose of this paper is to give some cause for optimism.

불행히도 이것이 진실입니다.

단순함은 달성하기 어렵다.

…하지만 이 논문의 목적은 긍정적으로 볼 수 있는 근거를 제시하는 것입니다.

One final point is that the type of complexity we are discussing in this paper is that which makes large systems hard to understand. It is this that causes us to expend huge resources in creating and maintaining such systems. This type of complexity has nothing to do with complexity theory — the branch of computer science which studies the resources consumed by a machine executing a program. The two are completely unrelated — it is a straightforward matter to write a small program in a few lines which is incredibly simple (in our sense) and yet is of the highest complexity class (in the complexity theory sense). From this point on we shall only discuss complexity of the first kind.

We shall look at what we consider to be the major common causes of complexity (things which make understanding difficult) after first discussing exactly how we normally attempt to understand systems.

마지막으로 이 논문에서 논의하는 종류의 복잡성은, '대규모 시스템을 이해하기 어렵게 만드는 종류의 복잡성'을 말한다는 것입니다. '이런 종류의 복잡성' 때문에 우리는 시스템을 만들고 유지보수하는 데에 막대한 자원을 소모하게 됩니다. 프로그램을 실행하는 기계가 소비하는 리소스를 연구하는 컴퓨터 과학의 한 분야인 '복잡성 이론'과 '이런 종류의 복잡성'은 아무런 관련이 없습니다. 몇 줄로 된 작은 프로그램은 우리가 보기에는 매우 간단한 것이지만, 복잡성 이론의 관점에서 보면 가장 높은 복잡성 유형에 속하는 문제인 것입니다.

이제부터 우리는 첫 번째 종류의 복잡성에 대해서만 논의하겠습니다.

우리는 일단 시스템을 이해하려고 할 때 보통 어떤 방식으로 노력하는지에 대해 정확히 논의한 후, 이해를 어렵게 만드는 복잡성의 주요한 공통적인 원인들에 대해 살펴보려 합니다.

3 Approaches to Understanding

시스템을 이해하려 할 때의 접근 방식들

We argued above that the danger of complexity came from its impact on our attempts to understand a system. Because of this, it is helpful to consider the mechanisms that are commonly used to try to understand systems. We can then later consider the impact that potential causes of complexity have on these approaches. There are two widely-used approaches to understanding systems (or components of systems):

Testing This is attempting to understand a system from the outside — as a "black box". Conclusions about the system are drawn on the basis of observations about how it behaves in certain specific situations. Testing may be performed either by human or by machine. The former is more common for whole-system testing, the latter more common for individual component testing.

Informal Reasoning This is attempting to understand the system by examining it from the inside. The hope is that by using the extra information available, a more accurate understanding can be gained.

앞에서 우리는 '시스템을 이해하기 어렵게 만든다'는 지점에서 복잡성이 위험하다고 주장했습니다. 따라서, 시스템을 이해하려 할 때 일반적으로 사용되곤 하는 메커니즘을 살펴보는 것이 도움이 될 것입니다. 그리고 나서 복잡성의 잠재적 원인이 이러한 접근 방식에 미치는 영향을 나중에 고려할 수 있을 것입니다. 시스템, 또는 시스템을 구성하는 컴포넌트들을 이해하려 할 때 널리 사용되는 두 가지 접근 방식은 다음과 같습니다.

테스팅

이 방법은 시스템을 '블랙박스'처럼 외부의 관점에서 이해하려 시도하는 것입니다. 따라서 특정한 상황에서 시스템이 어떻게 동작하는지에 대한 관찰을 바탕으로 시스템에 대한 결론을 도출합니다. 이러한 테스트는 사람 또는 머신에 의해 수행될 수 있습니다. 전자는 전체 시스템 테스트에 더 많이 사용되고, 후자는 개별 컴포넌트 테스트에 더 많이 사용됩니다.

비형식적 추론

이 방법은 시스템을 내부에서 살펴보면서 이해하려는 것입니다. 가용한 추가적인 정보를 사용하여 보다 정확한 이해를 얻기를 바라는 활동입니다.

Of the two informal reasoning is the most important by far. This is because — as we shall see below — there are inherent limits to what can be achieved by testing, and because informal reasoning (by virtue of being an inherent part of the development process) is always used. The other justification is that improvements in informal reasoning will lead to less errors being created whilst all that improvements in testing can do is to lead to more errors being detected. As Dijkstra said in his Turing award speech [Dij72, EWD340]:

"Those who want really reliable software will discover that they must find means of avoiding the majority of bugs to start with."

and as O’Keefe (who also stressed the importance of “understanding your problem” and that “Elegance is not optional”) said [O’K90]:

“Our response to mistakes should be to look for ways that we can avoid making them, not to blame the nature of things.”

이들 중 '비형식적 추론'이 훨씬 중요합니다. 아래에서 살펴보겠지만, 테스팅을 통해 얻을 수 있는 것에는 본질적인 한계가 있는 반면, '비형식적 추론'은 개발 프로세스의 본질적인 부분이므로 항상 사용되고 있기 때문입니다. 그리고 비형식적 추론이 개선되면 오류가 더 적게 발생하게 되지만, 테스팅은 개선한다 해도 더 많은 오류를 찾아낼 수 있을 뿐입니다. Dijkstra는 튜링상 수상 강연에서 다음과 같이 말한 바 있습니다.

"정말 신뢰할 수 있는 소프트웨어를 원하는 사람들은, 처음부터 대부분의 버그를 피할 수 있는 방법을 찾아야 한다는 것을 깨닫게 될 것입니다."

그리고 ("문제를 이해하는 것"의 중요성과 "우아함은 선택 사항이 아니다"라는 것을 강조한) O'Keefe는 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

"실수에 대한 우리의 대응은, 사물의 본질을 탓하는 것이 아니라 실수를 저지르지 않을 방법을 찾는 것이어야 합니다."

The key problem with testing is that a test (of any kind) that uses one particular set of inputs tells you nothing at all about the behaviour of the system or component when it is given a different set of inputs. The huge number of different possible inputs usually rules out the possibility of testing them all, hence the unavoidable concern with testing will always be — have you performed the right tests?. The only certain answer you will ever get to this question is an answer in the negative — when the system breaks. Again, as Dijkstra observed [Dij71, EWD303]:

“testing is hopelessly inadequate….(it) can be used very effectively to show the presence of bugs but never to show their absence.”

We agree with Dijkstra. Rely on testing at your peril.

테스팅의 중요한 문제점은 (어떤 종류가 되었건 간에) 특정 입력 세트를 사용하는 테스트는, 다른 입력 세트가 주어졌을 때 시스템 또는 컴포넌트의 동작에 대해 전혀 알려주지 않는다는 것입니다.

가능한 입력의 경우의 수가 너무 많기 때문에 일반적으로 모든 입력을 테스트하는 것은 불가능합니다. 따라서 테스트에 대한 피할 수 없는 고민은 항상 '올바른 테스트를 수행했는가?'가 될 수 밖에 없습니다. 이 질문에 대한 유일하고 확실한 답은 바로, 시스템에 고장이 났을 때 발생하는 부정적인 결과를 확인하는 것입니다. 다시 Dijkstra를 인용해보겠습니다.

"테스트는 절망적으로 부적절하다… (테스트는) 버그의 존재를 보여주는 데는 매우 효과적으로 사용될 수 있지만 버그가 없다는 것을 보여주는 데에는 결코 사용될 수 없다."

우리도 Dijkstra의 말에 동의합니다. 테스팅에 과도하게 의존하면 위험합니다.

This is not to say that testing has no use. The bottom line is that all ways of attempting to understand a system have their limitations (and this includes both informal reasoning — which is limited in scope, imprecise and hence prone to error — as well as formal reasoning — which is dependent upon the accuracy of a specification). Because of these limitations it may often be prudent to employ both testing and reasoning together.

It is precisely because of the limitations of all these approaches that simplicity is vital. When considered next to testing and reasoning, simplicity is more important than either. Given a stark choice between investment in testing and investment in simplicity, the latter may often be the better choice because it will facilitate all future attempts to understand the system — attempts of any kind.

이것은 테스팅이 무의미하다는 말이 아닙니다. 시스템을 이해하려는 모든 방법에는 한계가 있다는 것이 핵심입니다. (여기에는 범위가 제한적이고 부정확해서 오류가 발생하기 쉬운 '비형식적 추론'과, 스펙의 정확성에 의존하는 '형식적 추론'이 모두 포함됩니다.) 이러한 한계로 인해 테스팅과 추론을 함께 사용하는 것이 현명한 선택일 수 있습니다.

이러한 모든 접근 방법들에 한계가 있기 때문에, 단순성이 매우 중요합니다. 테스팅, 그리고 추론과 동등하게 놓고 고려해 봤을 때, 단순성은 이들 중 어느 것보다 더 중요합니다. 테스팅에 대한 투자와 단순성에 대한 투자 사이에서 강력한 선택을 해야 하는 상황이라면, 단순성에 대한 투자가 더 나은 선택일 수 있습니다. 왜냐하면 단순성은 '어떠한 방식으로든 시스템을 이해하려 하는 모든 미래의 시도'들을 용이하게 만들어주기 때문입니다.

4 Causes of Complexity

복잡성의 원인

In any non-trivial system there is some complexity inherent in the problem that needs to be solved. In real large systems however, we regularly encounter complexity whose status as “inherent in the problem” is open to some doubt. We now consider some of these causes of complexity.

사소하지 않은 모든 시스템에서는 해결해야 하는 문제 자체에 복잡성이 내재되어 있습니다. 그러나 실제의 대규모 시스템에서 마주하게 되는 복잡성들은 '문제에 내재된'것인지 아닌지 구별하기 어려운 경우가 자주 있습니다. 이제 이러한 복잡성의 원인들 중 몇 가지를 살펴보겠습니다.

4.1 Complexity caused by State

Anyone who has ever telephoned a support desk for a software system and been told to “try it again”, or “reload the document”, or “restart the program”, or “reboot your computer” or “re-install the program” or even “re-install the operating system and then the program” has direct experience of the problems that state1 causes for writing reliable, understandable software.

The reason these quotes will sound familiar to many people is that they are often suggested because they are often successful in resolving the problem. The reason that they are often successful in resolving the problem is that many systems have errors in their handling of state. The reason that many of these errors exist is that the presence of state makes programs hard to understand. It makes them complex.

누구든지 소프트웨어 시스템 서비스 센터에 전화를 걸었을 때 "다시 시도해 보세요", "문서 파일을 다시 로드해보세요", "프로그램을 재시작하세요", "컴퓨터를 재부팅하세요", "프로그램을 재설치하세요", 심지어 "운영체제를 다시 설치한 다음, 프로그램을 재설치하세요" 같은 말들을 들어본 사람이라면, 신뢰할 수 있고 이해하기 쉬운 소프트웨어를 작성하는 데 '상태'1가 일으키는 문제를 직접 경험한 적이 있는 셈입니다.

고객센터 전화통화에서 듣는 이런 말들이 많은 사람들에게 친숙하게 들리는 이유는, 문제를 해결하는 데 성공하는 경우가 많은 편이기 때문입니다. 그리고 이런 방법들이 종종 문제를 해결하는 데 성공하는 이유는, 많은 시스템들이 '상태'를 처리하는 데 오류가 있기 때문입니다. 이러한 오류가 많이 발생하는 이유는 상태의 존재가 프로그램을 이해하기 어렵게 만들기 때문입니다. 상태는 프로그램을 복잡하게 만듭니다.

When it comes to state, we are in broad agreement with Brooks’ sentiment when he says [Bro86]:

“From the complexity comes the difficulty of enumerating, much less understanding, all the possible states of the program, and from that comes the unreliability”

— we agree with this, but believe that it is the presence of many possible states which gives rise to the complexity in the first place, and:

“computers. . . have very large numbers of states. This makes conceiving, describing, and testing them hard. Software systems have orders-of-magnitude more states than computers do.”

상태에 대해 [[/people/fred-brooks]]{Fred Brooks}가 다음과 같이 말한 것에 대해 우리는 폭넓게 동의합니다.

"복잡성으로 인해, 프로그램의 모든 가능한 상태를 열거하는 것이 어려워지며, 이를 이해하는 것도 더욱 어려워지고, 그로 인해 결국 신뢰성이 떨어지게 됩니다."

이에 동의하긴 하지만, 우리는 애초에 가능한 상태가 많다는 것 자체가 복잡성을 야기한다고 믿습니다.

"컴퓨터는 매우 많은 수의 상태를 갖고 있습니다. 따라서 상태를 구상하고, 설명하고, 테스트하기란 어렵습니다. 소프트웨어 시스템은 컴퓨터보다 훨씬 더 많은 상태를 갖고 있습니다."

4.1.1 Impact of State on Testing

상태가 테스트에 미치는 영향

The severity of the impact of state on testing noted by Brooks is hard to over-emphasise. State affects all types of testing — from system-level testing (where the tester will be at the mercy of the same problems as the hapless user just mentioned) through to component-level or unit testing. The key problem is that a test (of any kind) on a system or component that is in one particular state tells you nothing at all about the behaviour of that system or component when it happens to be in another state.

[[/people/fred-brooks]]{Brooks}가 언급한 상태가 테스트에 미치는 영향의 심각성은 아무리 강조해도 지나치지 않습니다. 상태는 시스템 수준 테스트(테스터가 방금 언급한 불행한 사용자와 같은 문제를 겪게 될 것입니다)에서부터 컴포넌트 수준 테스트, 단위 테스트에 이르기까지 모든 유형의 테스트에 영향을 미칩니다. 핵심적인 문제는 특정 상태에 있는 시스템이나 컴포넌트에 대한 테스트(모든 종류의 테스트)가 해당 시스템이나 컴포넌트가 '다른 상태일 때의 동작'에 대해 전혀 알려주지 않는다는 것입니다.

The common approach to testing a stateful system (either at the component or system levels) is to start it up such that it is in some kind of “clean” or “initial” (albeit mostly hidden) state, perform the desired tests using the test inputs and then rely upon the (often in the case of bugs ill-founded) assumption that the system would perform the same way — regardless of its hidden internal state — every time the test is run with those inputs.

상태기반 시스템(컴포넌트 또는 시스템 레벨에서)을 테스트하는 일반적인 접근방법은,

- 시스템이 '깨끗'하거나 '초기' 상태가 되도록 시작하고(초기 상태라 해도 대부분의 상태값은 숨겨져 있다),

- 테스트 입력을 사용하여 원하는 테스트를 수행한 다음,

- 해당 입력으로 테스트를 실행할 때마다 시스템이 숨겨진 내부 상태와 관계 없이 똑같은 방식으로 작동할 거라는 가정(종종 원인을 알 수 없는 버그가 나온다)에 의존하는 것입니다.

In essence, this approach is simply sweeping the problem of state under the carpet. The reasons that this is done are firstly because it is often possible to get away with this approach and more crucially because there isn’t really any alternative when you’re testing a stateful system with a complicated internal hidden state.

이 접근방법은 본질적으로 '상태 문제'를 바닥 청소를 하지 않고 카펫 밑으로 쑤셔넣는 것에 불과합니다. 이렇게 하는 이유는,

- 첫째, 이 접근법을 통해 문제를 피할 수 있는 경우가 많기 때문이고,

- 둘쟤, 결정적으로 더 복잡한 '내부적으로 숨겨진 상태'가 있는 상태기반 시스템을 테스트할 때는 실제로 별다른 대안이 없기 때문입니다.

The difficulty of course is that it’s not always possible to “get away with it” — if some sequence of events (inputs) can cause the system to “get into a bad state” (specifically an internal hidden state which was different from the one in which the test was performed) then things can and do go wrong. This is what is happening to the hypothetical support-desk caller discussed at the beginning of this section. The proposed remedies are all attempts to force the system back into a “good internal state”.

물론, 어떤 연속된 이벤트(입력)들로 인해 시스템이 "나쁜 상태"로 빠질 수 있다면(특히 테스트해본 상태와 다른, 내부의 숨겨진 상태로), 상황이 실제로 잘못될 수 있다는 점이 어렵습니다.

이 장의 시작 부분에서 설명한 가상의 고객센터로 전화를 건 발신자에게는 이런 일이 발생하고 있는 것입니다. 그 고객에게 제안된 해결 방법은 모두, 시스템을 "좋은 내부 상태"로 되돌리려는 시도였습니다.

This problem (that a test in one state tells you nothing at all about the system in a different state) is a direct parallel to one of the fundamental problems with testing discussed above — namely that testing for one set of inputs tells you nothing at all about the behaviour with a different set of inputs. In fact the problem caused by state is typically worse — particularly when testing large chunks of a system — simply because even though the number of possible inputs may be very large, the number of possible states the system can be in is often even larger.

이 문제(하나의 상태를 토대로 한 테스트가 다른 상태의 시스템에 대해 전혀 알려주지 않는다는 점)는 위에서 설명한 테스팅의 근본적인 문제 중 하나, 즉 '하나의 입력 세트에 대한 테스트'가 '다른 입력 세트의 동작에 대해 전혀 알려주지 않는다'는 문제와 직접적으로 유사합니다.

사실 상태로 인한 문제는 일반적으로 특히 시스템의 큰 덩어리를 테스트하는 경우일수록 더 심각합니다. 가능한 입력의 수도 매우 많을 수 있지만, 시스템이 가질 수 있는 가능한 상태의 수가 그보다 훨씬 더 많은 경우가 많기 때문입니다.

These two similar problems — one intrinsic to testing, the other coming from state — combine together horribly. Each introduces a huge amount of uncertainty, and we are left with very little about which we can be certain if the system/component under scrutiny is of a stateful nature.

이 두 가지의 유사한 문제(하나는 테스트에 내재된 문제, 다른 하나는 상태에서 비롯된 문제)는 끔찍할 정도로 결합되어 있습니다. 이 문제들 각각은 엄청난 불확실성을 야기하며, 조사 대상인 시스템/컴포넌트가 상태의 성격을 띄고 있는지를 확신할 수 있는 방법도 거의 없습니다.

4.1.2 Impact of State on Informal Reasoning

상태가 비형식적 추론에 미치는 영향

In addition to causing problems for understanding a system from the outside, state also hinders the developer who must attempt to reason (most commonly on an informal basis) about the expected behaviour of the system “from the inside”.

상태는 외부에서 시스템을 이해하는 데 문제를 일으킬 뿐만 아니라, '내부에서' 시스템의 예상 동작을 추론(일반적으로 비형식적인 추론 기반)해야 하는 개발자에게도 방해가 됩니다.

The mental processes which are used to do this informal reasoning often revolve around a case-by-case mental simulation of behaviour: “if this variable is in this state, then this will happen — which is correct — otherwise that will happen — which is also correct”. As the number of states — and hence the number of possible scenarios that must be considered — grows, the effectiveness of this mental approach buckles almost as quickly as testing (it does achieve some advantage through abstraction over sets of similar values which can be seen to be treated identically).

이러한 비형식적 추론에 동원되는 정신적 프로세스는 종종 동작 사례에 대한 정신적인 시뮬레이션을 중심으로 이루어집니다. "만약에 이 변수가 이런 상태에 있다면, 이런 일이 일어나겠지. 음 이건 맞고, 그렇지 않으면 저런 일이 일어나겠지. 음 이것도 맞고." 이런 식으로 말이죠.

상태의 수와 고려해야 하는 가능한 시나리오들의 수가 증가함에 따라, 이런 정신적인 접근 방식의 효율성은 테스팅만큼이나 빠르게 떨어져버립니다. (다만 테스팅은 동일하게 취급되는 것으로 볼 수 있는 유사한 값 집합에 비해서는 추상화를 통해 꽤나 이득을 얻을 수 있습니다.)

One of the issues (that affects both testing and reasoning) is the exponential rate at which the number of possible states grows — for every single bit of state that we add we double the total number of possible states. Another issue — which is a particular problem for informal reasoning — is contamination.

테스팅과 추론 모두에 영향을 미치는 문제 중 하나는, 가능한 상태의 수가 기하급수적으로 증가한다는 것입니다. 상태를 하나 추가할 때마다 가능한 상태의 총 수가 두 배로 늘어납니다. 그리고 비형식적 추론에서 특히 문제가 되는 또 다른 문제는 오염(contamination)입니다.

Consider a system to be made up of procedures, some of which are stateful and others which aren’t. We have already discussed the difficulties of understanding the bits which are stateful, but what we would hope is that the procedures which aren’t themselves stateful would be more easy to comprehend. Alas, this is largely not the case. If the procedure in question (which is itself stateless) makes use of any other procedure which is stateful — even indirectly — then all bets are off, our procedure becomes contaminated and we can only understand it in the context of state. If we try to do anything else we will again run the risk of all the classic state-derived problems discussed above. As has been said, the problem with state is that “when you let the nose of the camel into the tent, the rest of him tends to follow”.

어떤 시스템 하나가 프로시저들로 만들어져 있는데, 그 프로시저 중 몇몇은 상태 기반이고 나머지는 그렇지 않다고 가정해 봅시다. 우리는 이미 상태 기반 비트를 이해하는 것에 대한 어려움을 이야기한 바 있습니다. 따라서 상태 기반이 아닌 프로시저는 이해하기 쉬우면 좋겠지만, 아쉽게도 그렇지 않습니다.

만약 문제의 프로시저(stateless)가 '간접적으로라도' 상태 기반의 다른 프로시저를 사용한다면, 이 프로시저도 오염이 되어 '상태의 문맥'에서만 이해할 수 있게 되어버립니다. 그리고 그 외의 다른 작업을 시도한다 해도 위에서 언급한 전형적인 상태 기반 문제들을 다시 한 번 마주하게 될 위험이 있습니다. 앞에서 말했듯이, 상태의 문제는 "낙타의 코를 텐트 안으로 들여보내면, 낙타의 나머지 몸뚱이도 코를 따라가는 경향이 있다" 는 말과 비슷합니다.

As a result of all the above reasons it is our belief that the single biggest remaining cause of complexity in most contemporary large systems is state, and the more we can do to limit and manage state, the better.

위의 모든 이유로 인해, 대부분의 현대적인 대규모 시스템에서 복잡성을 유발하는 가장 큰 원인은 상태이며, 상태를 제한하고 관리하기 위해 할 수 있는 일이 많을수록 더 좋다고 생각합니다.

4.2 Complexity caused by Control

제어로 인한 복잡성

Control is basically about the order in which things happen.

'제어'는 기본적으로 일이 진행되는 순서에 대한 것입니다.

The problem with control is that very often we do not want to have to be concerned with this. Obviously — given that we want to construct a real system in which things will actually happen — at some point order is going to be relevant to someone, but there are significant risks in concerning ourselves with this issue unnecessarily.

제어의 문제점은 우리가 이 문제에 대해 신경쓰고 싶지 않은 경우가 많다는 것입니다. 물론, '실제로 뭔가 일이 일어나는 시스템'을 구축하고자 한다면 순서 문제는 언젠가는 중요해질 것입니다. 그러나 이 문제에 불필요하게 신경을 쓰는 것은 상당한 위험이 따르는 일입니다.

Most traditional programming languages do force a concern with ordering — most often the ordering in which things will happen is controlled by the order in which the statements of the programming language are written in the textual form of the program. This order is then modified by explicit branching instructions (possibly with conditions attached), and subroutines are normally provided which will be invoked in an implicit stack.

대부분의 전통적인 프로그래밍 언어는 '순서'에 대한 고려를 필요로 합니다. 주로 프로그래밍 언어의 명령문이 프로그램의 텍스트 형식으로 작성된 순서가 실행될 일들의 순서를 결정하는 방식입니다. 이렇게 결정된 순서는 명시적인 제어 분기 명령어를 통해 변경될 수 있고, 이런 분기 명령에는 분기를 위한 조건이 붙을 수 있으며, 일반적으로 암묵적 스택에서 호출되는 서브루틴이 제공됩니다.

Of course a variety of evaluation orders is possible, but there is little variation in this regard amongst widespread languages.

물론 평가 순서는 다양한 방식으로도 가능하지만, 널리 사용되는 프로그래밍 언어들 사이에서는 큰 차이가 없습니다.

The difficulty is that when control is an implicit part of the language (as it almost always is), then every single piece of program must be understood in that context — even when (as is often the case) the programmer may wish to say nothing about this. When a programmer is forced (through use of a language with implicit control flow) to specify the control, he or she is being forced to specify an aspect of how the system should work rather than simply what is desired. Effectively they are being forced to over-specify the problem. Consider the simple pseudo-code below:

어려운 지점은 제어가 언어의 암묵적인 부분인 경우(거의 대부분이 해당됨), 프로그래머가 이에 대해 어떤 것도 명시적으로 표현하고 싶지 않은 경우에도 모든 프로그램을 해당 맥락에서 이해해야만 한다는 것입니다.

프로그래머가 (암묵적 제어 흐름을 가진 언어를 사용해서) 제어를 명시하도록 강요받고 있는 경우라면, 원하건 원하지 않건 시스템이 어떻게 작동해야 하는지에 대한 상세 내역을 지정할 수 밖에 없게 됩니다. 사실상 문제를 과도할 정도로 상세히 명시하도록 강요당하고 있는 것입니다.

아래의 간단한 의사 코드를 읽어 봅시다.

a := b + 3 c := d + 2 e := f * 4

In this case it is clear that the programmer has no concern at all with the order in which (i.e. how) these things eventually happen. The programmer is only interested in specifying a relationship between certain values, but has been forced to say more than this by choosing an arbitrary control flow. Often in cases such as this a compiler may go to lengths to establish that such a requirement (ordering) — which the programmer has been forced to make because of the semantics of the language — can be safely ignored.

이런 코드의 경우, 프로그래머는 이런 일들이 발생하는 순서(즉, 방법)에 대해서는 전혀 관심이 없음이 분명해 보입니다. 이 코드를 작성한 프로그래머는 특정한 값들 사이의 관계를 지정하는 데에만 관심이 있습니다. 그러나 임의의 제어 흐름을 선택함으로써 의도한 것보다 더 많은 것을 표현하도록 강요받고 있습니다.

이런 경우 컴파일러는 '언어의 의미론 때문에 프로그래머가 어쩔 수 없이 만든' 이런 요구 사항들(순서)을 안전하게 무시할 수 있다는 것을 입증하기 위해 많은 노력을 기울이게 될 수 있습니다.

In simple cases like the above the issue is often given little consideration, but it is important to realise that two completely unnecessary things are happening — first an artificial ordering is being imposed, and then further work is done to remove it.

위의 예제와 같은 단순한 경우에는 이런 문제를 거의 고려하지 않는 경우가 많습니다. 그러나 먼저 '인위적인 순서'가 부여되었다가 이런 것을 또 제거하기 위한 추가적인 작업이 수행되는 등, 완전히 불필요한 두 가지 일이 발생하고 있다는 사실을 인식하는 것이 중요합니다.

This seemingly innocuous occurrence can actually significantly complicate the process of informal reasoning. This is because the person reading the code above must effectively duplicate the work of the hypothetical compiler — they must (by virtue of the definition of the language semantics) start with the assumption that the ordering specified is significant, and then by further inspection determine that it is not (in cases less trivial than the one above determining this can become very difficult). The problem here is that mistakes in this determination can lead to the introduction of very subtle and hard-to-find bugs.

별로 해롭지 않아 보이기도 하는 이 문제는, 실제로 비형식적 추론 과정을 상당히 복잡하게 만들 수 있습니다.

왜냐하면 위의 코드를 읽는 사람은 언어 의미론의 정의에 따라 지정된 '순서'가 중요하다는 가정 하에서 생각을 시작하여, 추가적인 검사를 통해 사실은 순서가 중요하지 않았다는 것을 판단해야 하기 때문입니다(위의 경우보다 덜 사소한 경우에는 이를 결정하는 것이 매우 어려워질 수 있습니다).

여기에서 문제는 이러한 판단을 잘못 내리면 매우 미묘하고 찾기 어려운 버그가 발생할 수 있다는 것입니다.

It is important to note that the problem is not in the text of the program above — after all that does have to be written down in some order — it is solely in the semantics of the hypothetical imperative language we have assumed. It is possible to consider the exact same program text as being a valid program in a language whose semantics did not define a run-time sequencing based upon textual ordering within the program.2

(프로그램을 결국 어떤 순서에 맞게 작성해야 한다는 것은 맞는 말이지만) 문제가 위의 예제 프로그램 텍스트에 있는 것이 아니라, 우리가 가정한 가상의 명령형 언어의 의미론에 문제가 있다는 점에 주목하는 것이 중요합니다.

프로그램 내의 텍스트 순서에 따른 런타임 순서를 정의하지 않는 언어에서는, 동일한 프로그램 텍스트가 (실행 순서에 대한 가정을 포함하지 않아도) '유효한 프로그램'으로 해석될 수 있습니다.2

Having considered the impact of control on informal reasoning, we now look at a second control-related problem, concurrency, which affects testing as well.

제어가 비형식적 추론에 미치는 영향을 고려했으니, 이제 테스팅에도 영향을 미치는 또 다른 제어 문제인 '동시성(concurrency)'에 대해서도 살펴보겠습니다.

Like basic control such as branching, but as opposed to sequencing, concurrency is normally specified explicitly in most languages. The most common model is “shared-state concurrency” in which specification for explicit synchronization is provided. The impacts that this has for informal reasoning are well known, and the difficulty comes from adding further to the number of scenarios that must mentally be considered as the program is read. (In this respect the problem is similar to that of state which also adds to the number of scenarios for mental consideration as noted above).

분기와 같은 기본 제어와 비슷하긴 하지만, 시퀀싱과는 달리 '동시성'은 일반적으로 대부분의 프로그래밍 언어에서는 명시적으로 지정됩니다.

가장 일반적인 모델은 명시적인 동기화를 위한 스펙이 제공되는 "공유 상태 동시성(shared-state concurrency)"입니다.

이것이 비형식적 추론에 미치는 영향은 잘 알려져 있으며, 프로그램을 읽는 동안 고려해야 하는 가능한 시나리오의 수가 증가함으로써 어려움이 따르는 것도 알려져 있습니다. (이 문제는 이전에 언급한 '상태'의 문제와 비슷하게, 고려해야 하는 가능한 시나리오의 수가 증가한다는 점에서 어려움이 있습니다.)

Concurrency also affects testing, for in this case, we can no longer even be assured of result consistency when repeating tests on a system — even if we somehow ensure a consistent starting state. Running a test in the presence of concurrency with a known initial state and set of inputs tells you nothing at all about what will happen the next time you run that very same test with the very same inputs and the very same starting state… and things can’t really get any worse than that.

동시성은 테스팅에도 영향을 미치는데, 동시성이 관여되는 경우 초기 상태를 어떻게든 일정하게 유지한다 해도 시스템에서 테스트를 반복할 때마다 결과의 일관성은 보장할 수 없게 됩니다.

알려진 초기 상태와 입력 집합이 있어도 동시성이 있는 상태에서 테스트를 실행하면, 똑같은 입력과 똑같은 초기 상태로 똑같은 테스트를 다시 실행한다 하더라도 어떤 일이 일어날지 전혀 예측할 수 없습니다… 이보다 더 나쁠 수는 없습니다.

4.3 Complexity caused by Code Volume

코드의 양 때문에 발생하는 복잡성

The final cause of complexity that we want to examine in any detail is sheer code volume.

마지막으로 살펴볼 복잡성의 원인은 코드의 양입니다.

This cause is basically in many ways a secondary effect — much code is simply concerned with managing state or specifying control. Because of this we shall often not mention code volume explicitly. It is however worth brief independent attention for at least two reasons — firstly because it is the easiest form of complexity to measure, and secondly because it interacts badly with the other causes of complexity and this is important to consider.

Brooks noted [Bro86]:

“Many of the classic problems of developing software products derive from this essential complexity and its nonlinear increase with size”

이 원인은 많은 측면에서 부차적인 효과(secondary effect)에 불과합니다. 많은 양의 코드는 단순히 상태를 관리하거나 제어를 지정하는 데 관여합니다. 따라서 코드의 양에 대해서는 가급적 명시적으로 언급하지 않을 것입니다. 그러나 적어도 두 가지 이유 때문에 이 문제는 별도로 주목할만한 가치가 있습니다.

- 첫째, 코드의 양은 측정하기 가장 쉬운 형태의 복잡성이기 때문입니다.

- 둘째, 코드의 양은 복잡성의 다른 원인과 부정적으로 상호작용을 하는데, 이는 중요하게 고려해야 하는 문제입니다.

[[/people/fred-brooks]]{Brooks}는 다음과 같이 말했습니다.

"소프트웨어 제품 개발의 고전적인 문제들 중 상당수는, '본질적인 복잡성'과 그러한 복잡성이 크기에 따라 비선형적으로 증가한다는 것으로부터 유래합니다."

We basically agree that in most current systems this is true (we disagree with the word “essential” as already noted) — i.e. in most systems complexity definitely does exhibit nonlinear increase with size (of the code). This non-linearity in turn means that it’s vital to reduce the amount of code to an absolute minimum.

우리는 기본적으로 현대적인 시스템의 대부분에서 이 문제가 사실이라는 점에 동의합니다(이미 언급했듯이 "본질적인"이라는 단어에는 동의하지 않습니다). 즉, 대부분의 시스템에서 복잡성은 코드의 규모에 따라 비선형적으로 증가하는 것이 확실합니다.

이러한 비선형성은 결국 코드의 양을 가능한 한 최소한으로 줄이는 것이 중요하다는 것을 의미합니다.

We also want to draw attention to one of Dijkstra’s [Dij72, EWD340] thoughts on this subject:

“It has been suggested that there is some kind of law of nature telling us that the amount of intellectual effort needed grows with the square of program length. But, thank goodness, no one has been able to prove this law. And this is because it need not be true. … I tend to the assumption — up till now not disproved by experience — that by suitable application of our powers of abstraction, the intellectual effort needed to conceive or to understand a program need not grow more than proportional to program length.”

우리는 또한 이 주제에 대한 Dijkstra의 생각 중 하나에 주목하고 싶습니다.

"지적 노력의 양이, 프로그램 길이의 제곱에 비례하여 증가한다는 일종의 자연법칙이 있다는 주장이 제기되어 왔습니다. 하지만 다행히도, 아무도 이 법칙을 증명하지 못했습니다. 그리고 이 법칙은 꼭 사실일 필요도 없습니다. … 나는 지금까지의 경험을 통해, 추상화 능력을 적절히 적용하면 프로그램을 구상하거나 이해하는 데 필요한 지적 능력이 프로그램 길이에 비례하지 않아도 된다고 생각하는 편입니다.

We agree with this — it is the reason for our “in most current systems” caveat above.

We believe that — with the effective management of the two major complexity causes which we have discussed, state and control — it becomes far less clear that complexity increases with code volume in a non-linear way.

우리는 Dijkstra의 이 말에 동의하기 때문에 앞에서 "현대적인 시스템의 대부분에서"라고 주의깊게 언급한 것입니다.

앞에서 논의한 두 가지의 주요한 복잡성 원인인 '상태'와 '제어'를 효과적으로 관리한다면, 코드의 양에 따라 복잡성이 비선형적으로 증가하는 문제를 훨씬 약화시킬 것이라고 믿습니다.

4.4 Other causes of complexity

복잡성의 다른 원인들

Finally there are other causes, for example: duplicated code, code which is never actually used (“dead code”), unnecessary abstraction,3 missed abstraction, poor modularity, poor documentation…

All of these other causes come down to the following three (inter-related) principles:

마지막으로 그 외의 다른 원인들이 있습니다. 중복된 코드, 실제로는 사용되지 않는 코드("죽은 코드"), 불필요한 추상화,3 누락된 추상화, 적절하지 않은 모듈화, 좋지 않은 문서화…

Complexity breeds complexity There are a whole set of secondary causes of complexity. This covers all complexity introduced as a result of not being able to clearly understand a system. Duplication is a prime example of this — if (due to state, control or code volume) it is not clear that functionality already exists, or it is too complex to understand whether what exists does exactly what is required, there will be a strong tendency to duplicate. This is particularly true in the presence of time pressures.

복잡성은 복잡성을 낳는다

복잡성의 이차적인 원인은 다양합니다. 시스템을 명확하게 이해할 수 없기 때문에 발생하는 모든 복잡성이 여기에 포함됩니다. 중복이 이러한 복잡성의 대표적인 예입니다. (상태, 제어 또는 코드의 양 때문에) 기능이 이미 존재하는지 명확하지 않거나, 기존의 기능이 요구되는 기능을 정확히 수행하는지 이해하기가 너무 복잡하다면, 중복의 가능성이 높아집니다. 특히 일정의 압박이 있는 경우에 더욱 그렇습니다.

Simplicity is Hard This was noted above — significant effort can be required to achieve simplicity. The first solution is often not the most simple, particularly if there is existing complexity, or time pressure. Simplicity can only be attained if it is recognised, sought and prized.

단순함은 달성하기 어렵다

앞에서 언급한 바와 같이 단순성을 달성하기 위해서는 상당한 노력이 필요할 수 있습니다. 이미 존재하는 복잡성이 있거나 일정의 압박이 있는 경우에는, 첫 번째 솔루션이 가장 단순한 종류의 것이 아닌 경우가 많습니다.

단순함을 인식하고, 추구하고, 중요하게 여기는 경우에만 단순함을 달성할 수 있습니다.

Power corrupts What we mean by this is that, in the absence of language-enforced guarantees (i.e. restrictions on the power of the language) mistakes (and abuses) will happen. This is the reason that garbage collection is good — the power of manual memory management is removed. Exactly the same principle applies to state — another kind of power. In this case it means that we need to be very wary of any language that even permits state, regardless of how much it discourages its use (obvious examples are ML and Scheme). The bottom line is that the more powerful a language (i.e. the more that is possible within the language), the harder it is to understand systems constructed in it.

권력은 부패한다

이것은 언어에 대한 제한(즉, 언어의 권력에 대한 제한)이 없으면 실수 및 남용이 발생할 수 있다는 뜻입니다. 가비지 컬렉션이 좋은 이유이기도 합니다. 가비지 컬렉션은 수동 메모리 관리의 권력을 제거하기 때문입니다.

이와 동일한 원칙이 '상태'라는 또 다른 형태의 권력에도 적용됩니다. 이 경우에는 상태를 허용하는 모든 언어를 사용할 때에는 아무리 사용을 억제하더라도, 극도로 주의해야 한다는 뜻입니다(ML과 Scheme이 대표적인 예입니다).

결론은 강력한 언어일수록(즉, 언어 내에서 가능한 것이 많을수록) 그 언어로 구성된 시스템은 이해하기가 더 어렵다는 것입니다.

Some of these causes are of a human-nature, others due to environmental issues, but all can — we believe — be greatly alleviated by focusing on effective management of the complexity causes discussed in sections 4.1–4.3.

이러한 원인 중 일부는 인간의 본성에 기인하는 것이고, 다른 일부는 환경 문제로 비롯된 것들입니다. 그러나 우리는 4.1~4.3 절에서 논의한 복잡성의 원인을 효과적으로 관리하는 데 집중하면 이런 원인들을 모두 상당히 완화할 수 있다고 믿습니다.

5 Classical approaches to managing complexity

복잡성 관리를 위한 고전적인 접근법

The different classical approaches to managing complexity can perhaps best be understood by looking at how programming languages of each of the three major styles (imperative, functional, logic) approach the issue. (We take object-oriented languages as a commonly used example of the imperative style).

복잡성 관리에 대한 다양한 고전적인 접근법은, 세 가지의 주요 스타일(명령형, 함수형, 논리형)의 프로그래밍 언어가 이 문제에 접근하는 방식을 살펴보면 가장 잘 이해할 수 있을 것입니다. (우리는 객체지향 언어를 명령형 스타일의 일반적인 예로 삼습니다.)

5.1 Object-Orientation

객체지향

Object-orientation — whilst being a very broadly applied term (encompassing everything from Java-style class-based to Self-style prototype-based languages, from single-dispatch to CLOS-style multiple dispatch languages, and from traditional passive objects to the active / actor styles) — is essentially an imperative approach to programming. It has evolved as the dominant method of general software development for traditional (von-Neumann) computers, and many of its characteristics spring from a desire to facilitate von-Neumann style (i.e. state-based) computation.

객체지향은 매우 광범위하게 적용되는 용어이지만(Java 스타일의 class 기반 언어에서 Self 스타일의 prototype 기반 언어, 단일 디스패치 언어부터 CLOS 스타일의 다중 디스패치 언어, 그리고 전통적인 수동 객체부터 active/actor 스타일까지 모두 객체지향에 포함됩니다), 그 본질은 명령형(imperative) 프로그래밍 접근법입니다.

이는 전통적인(폰 노이만) 컴퓨터에 대한 일반적인 소프트웨어 개발 방법으로 발전해 왔으며, 그 특성 중 많은 것들은 폰 노이만 스타일(즉, 상태 기반)의 계산을 용이하게 하고자 하는 욕구에서 비롯됩니다.

5.1.1 State

상태

In most forms of object-oriented programming (OOP) an object is seen as consisting of some state together with a set of procedures for accessing and manipulating that state.

This is essentially similar to the (earlier) idea of an abstract data type (ADT) and is one of the primary strengths of the OOP approach when compared with less structured imperative styles. In the OOP context this is referred to as the idea of encapsulation, and it allows the programmer to enforce integrity constraints over an object’s state by regulating access to that state through the access procedures (“methods”).

대부분의 객체지향 프로그래밍(OOP)에서 '객체'는 특정한 상태와 그 상태에 접근하고 조작하기 위한 절차들의 집합으로 구성되는 것으로 간주할 수 있습니다.

이는 본질적으로 추상 데이터 타입(ADT)의 (이전) 개념과 유사하며, 덜 구조화된 명령형 스타일과 비교했을 때 OOP 접근법의 주요 장점 중 하나입니다. OOP 맥락에서는 이것을 캡슐화라 부릅니다. 이를 통해 프로그래머는 접근 프로시저("메소드")를 통한 상태 접근을 제한하는 방법으로 객체의 상태에 대한 무결성을 유지하게 합니다.

One problem with this is that, if several of the access procedures access or manipulate the same bit of state, then there may be several places where a given constraint must be enforced (these different access procedures may or may not be within the same file depending on the specific language and whether features, such as inheritance, are in use). Another major problem4 is that encapsulation-based integrity constraint enforcement is strongly biased toward single-object constraints and it is awkward to enforce more complicated constraints involving multiple objects with this approach (for one thing it becomes unclear where such multiple-object constraints should reside).

이 방법의 한 가지 문제점은 여러 접근 프로시저가 하나의 상태 비트에 접근하거나 그걸 조작하는 경우에, 주어진 제약 조건을 적용해야 하는 위치가 여러 곳에 있을 수 있다는 것입니다(특정 언어와 상속과 같은 기능의 사용 여부에 따라 서로 다른 접근 프로시저가 같은 파일에 있을 수도 있고, 다른 파일에 있을 수도 있습니다).

그리고 또 다른 주요한 문제점4은 '캡슐화 기반의 무결성 제약 조건' 적용이, 주로 '단일 객체에 대한 제약'을 중심으로 하기 때문에, 이런 접근 방식으로는 여러 객체가 관련된 더 복잡한 제약 조건을 적용하기가 어렵다는 것입니다(일단 이런 다중 객체 제약 조건을 어디에 위치시켜야 하는지가 불분명합니다).

Identity and State

동일성과 상태

There is one other intrinsic aspect of OOP which is intimately bound up with the issue of state, and that is the concept of object identity.

상태 문제와 밀접하게 연관되어 있는 OOP의 또다른 본질적인 측면이 하나 더 있습니다. 바로 객체의 동일성 개념입니다.

In OOP, each object is seen as being a uniquely identifiable entity regardless of its attributes. This is known as intensional identity (in contrast with extensional identity in which things are considered the same if their attributes are the same). As Baker observed [Bak93]:

In a sense, object identity can be considered to be a rejection of the “relational algebra” view of the world in which two objects can only be distinguished through differing attributes.

OOP에서 각 객체는 속성값들과는 관계없이 고유하게 식별 가능한 엔티티로 간주됩니다. 이를 '내재적 동일성'이라 합니다(속성값들이 같으면 동일한 것으로 간주하는 '확장적 동일성'과 대조적인 개념입니다). Baker는 다음과 같이 언급한 바 있습니다.

어떤 의미에서, 객체 동일성은 서로 다른 속성을 통해서만 두 객체를 구별할 수 있는 '관계 대수'의 세계관을 거부하는 것으로 간주할 수 있습니다.

Object identity does make sense when objects are used to provide a (mutable) stateful abstraction — because two distinct stateful objects can be mutated to contain different state even if their attributes (the contained state) happen initially to be the same.

객체 동일성은 객체가 (변경 가능한) 상태 추상화(stateful abstraction)를 제공하는 데 사용될 때 의미가 있습니다. 왜냐하면 두 개의 서로 다른 상태 저장 객체는 초기에는 속성(포함된 상태)이 같더라도, 나중에는 서로 다른 상태를 갖고 있게 변경될 수 있기 때문입니다.

However, in other situations where mutability is not required (such as — say — the need to represent a simple numeric value), the OOP approach is forced to adopt techniques such as the creation of “Value Objects”, and an attempt is made to de-emphasise the original intensional concept of object identity and re-introduce extensional identity. In these cases it is common to start using custom access procedures (methods) to determine whether two objects are equivalent in some other, domain-specific sense. (One risk — aside from the extra code volume required to support this — is that there can no longer be any guarantee that such domain-specific equivalence concepts conform to the standard idea of an equivalence relation — for example there is not necessarily any guarantee of transitivity).

그러나 이런 변경 가능(mutability)이 필요하지 않은 다른 상황(예: 단순한 숫자값을 표현하는 경우)에서는 OOP식 접근 방법은 "값 객체(Value Objects)" 생성과 같은 기술을 채택할 수 밖에 없으며, 본래 의도했던 객체 동일성 컨셉이 아니라 확장적 동일성을 다시 도입하는 상황이 됩니다. 이러한 경우에는 커스텀 접근 프로시저(메소드)를 사용해 두 객체가 다른 도메인별 의미에서 동등한지 아닌지를 결정하는 것이 일반적입니다.

(이를 위해 추가해야 하는 코드의 양을 제외하고 생각한다 해도) 이런 방식은 도메인별 동등성 개념이 동등 관계(equivalence relation)의 표준 개념과 일치하는지에 대한 보장이 없다는 위험을 안고 있습니다. 예를 들어, 이행성(transitivity)을 보장할 수 없다는 문제도 있습니다.)

The intrinsic concept of object identity stems directly from the use of state, and is (being part of the paradigm itself) unavoidable. This additional concept of identity adds complexity to the task of reasoning about systems developed in the OOP style (it is necessary to switch mentally between the two equivalence concepts — serious errors can result from confusion between the two).

객체 동일성의 본질적인 개념은 '상태'의 사용에서 직접적으로 비롯되며, (패러다임 자체에서 나온 것이므로) 피할 수 없습니다. 이런 추가적인 동일성 개념은 OOP 스타일로 개발된 시스템에 대한 추론 작업에 복잡성을 더해줍니다(두 가지의 동등성 개념 사이를 정신적으로 전환해야 하며, 두 개념을 혼동하면 심각한 오류가 발생할 수 있습니다).

State in OOP

OOP의 상태

The bottom line is that all forms of OOP rely on state (contained within objects) and in general all behaviour is affected by this state. As a result of this, OOP suffers directly from the problems associated with state described above, and as such we believe that it does not provide an adequate foundation for avoiding complexity.

결론은 모든 형태의 OOP는 객체 내에 포함되는 상태에 의존하며, 일반적으로 모든 동작이 이 상태의 영향을 받는다는 것입니다. 그 결과, OOP는 앞에서 설명한 '상태'와 관련된 문제를 직접적으로 겪게 됩니다. 따라서 복잡성을 피하기 위한 적절한 기반을 제공하지 못한다고 생각합니다.

5.1.2 Control

제어

Most OOP languages offer standard sequential control flow, and many offer explicit classical “shared-state concurrency” mechanisms together with all the standard complexity problems that these can cause. One slight variation is that actor-style languages use the “message-passing” model of concurrency — they associate threads of control with individual objects and messages are passed between these. This can lead to easier informal reasoning in some cases, but the use of actor-style languages is not widespread.

대부분의 OOP 언어는 표준적인 순차적 제어 흐름을 제공합니다. 따라서 많은 언어가 명시적으로 고전적인 "공유 상태 동시성(shared-state concurrency)" 메커니즘을 제공하게 되기 때문에 이로 인해 발생할 수 있는 모든 표준적인 복잡성 문제도 함께 발생하게 됩니다.

한 가지 차이점이 있다면 액터 스타일의 언어에서는 제어 스레드를 개별 객체와 연결하고 그 객체들 사이에 메시지를 전달하는 '메시지 전달' 동시성을 사용한다는 점입니다. 이 기법을 사용하면 비형식적 추론이 더 쉬워질 수 있습니다. 그러나 액터 스타일 언어는 널리 사용되고 있지는 않습니다.

5.1.3 Summary — OOP

OOP 요약

Conventional imperative and object-oriented programs suffer greatly from both state-derived and control-derived complexity.

현존하는 명령형 및 객체지향 프로그램은 상태와 제어로 인한 복잡성에 큰 어려움을 겪습니다.

5.2 Functional Programming

함수형 프로그래밍

Whilst OOP developed out of a desire to offer improved ways of managing and dealing with the classic stateful von-Neumann architecture, functional programming has its roots in the completely stateless lambda calculus of Church (we are ignoring the even simpler functional systems based on combinatory logic). The untyped lambda calculus is known to be equivalent in power to the standard stateful abstraction of computation — the Turing machine.

고전적인 상태 기반(stateful) 폰 노이만 아키텍처를 관리하고 처리하는 개선된 방법을 제공하려는 의도에서 OOP는 개발되었습니다. 반면 함수형 프로그래밍은 Church의 완전한 무상태 기반의(stateless) 람다 계산법에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다(조합 논리에 기반한 더 단순한 함수형 시스템은 여기에서는 언급하지 않겠습니다).

타입 없는 람다 계산법은 표준 상태 저장 추상화 계산, 즉 튜링 머신과 동등한 성능을 발휘하는 것으로 알려져 있습니다.

5.2.1 State

상태

Modern functional programming languages are often classified as ‘pure’ — those such as Haskell[PJ+03] which shun state and side-effects completely, and ‘impure’ — those such as ML which, whilst advocating the avoidance of state and side-effects in general, do permit their use. Where not explicitly mentioned we shall generally be considering functional programming in its pure form.

현대적인 함수형 프로그래밍 언어는 '상태와 사이드 이펙트를 완전히 배제하는' Haskell 같은 '순수한' 언어와, '상태와 부작용의 회피를 옹호하면서도 사용을 허용하기는 하는' ML과 같은 '불순한' 언어로 분류되곤 합니다.

여기에서는 별도로 언급하지 않는 이상, 일반적으로는 순수한 형태의 함수형 프로그래밍을 고려하겠습니다.

The primary strength of functional programming is that by avoiding state (and side-effects) the entire system gains the property of referential transparency — which implies that when supplied with a given set of arguments a function will always return exactly the same result (speaking loosely we could say that it will always behave in the same way). Everything which can possibly affect the result in any way is always immediately visible in the actual parameters.

함수형 프로그래밍의 가장 큰 장점은 상태(와 부작용)를 피함으로써 전체 시스템이 참조 투명성이라는 특성을 얻게 된다는 것입니다. 이는 특정한 인수 집합이 제공될 때 함수가 항상 정확히 같은 결과를 반환한다는 것을 의미합니다(대충 말하자면 항상 같은 방식으로 동작한다고 할 수 있습니다).

어떤 방식으로든 '결과에 영향을 줄 수 있는 모든 것'을 항상 실제 매개변수에서 바로 확인할 수 있다는 것입니다.

It is this cast iron guarantee of referential transparency that obliterates one of the two crucial weaknesses of testing as discussed above. As a result, even though the other weakness of testing remains (testing for one set of inputs says nothing at all about behaviour with another set of inputs), testing does become far more effective if a system has been developed in a functional style.

참조 투명성의 이런 철저한 보장은, 앞에서 설명한 테스팅의 두 가지 중요한 약점 중 하나를 원천봉쇄하는 것입니다.

결과적으로 테스트의 다른 약점(어떤 입력 집합에 대한 테스트만으로는, 다른 입력 집합에 대한 동작에 대해 전혀 알 수 없음)이 남아있게 되긴 하지만, 시스템이 함수형 스타일로 개발되었다면 테스트는 훨씬 효과적이 됩니다.

By avoiding state functional programming also avoids all of the other state-related weaknesses discussed above, so — for example — informal reasoning also becomes much more effective.

상태를 회피함으로써, 함수형 프로그래밍은 상태와 관련된 앞에서 언급한 모든 약점을 회피하게 됩니다. 따라서 비형식적인 추론도 훨씬 효과적이 됩니다.

5.2.2 Control

제어

Most functional languages specify implicit (left-to-right) sequencing (of calculation of function arguments) and hence they face many of the same issues mentioned above. Functional languages do derive one slight benefit when it comes to control because they encourage a more abstract use of control using functionals (such as fold / map) rather than explicit looping.

There are also concurrent versions of many functional languages, and the fact that state is generally avoided can give benefits in this area (for example in a pure functional language it will always be safe to evaluate all arguments to a function in parallel).

(함수 인수의 계산 우선순위에 대해) 대부분의 함수형 언어는 암묵적으로 (왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로) 순서를 지정하므로 위에서 언급한 것과 동일한 문제에 직면하게 됩니다.

함수형 언어는 명시적인 loop 대신, 함수(예: fold/map5)를 사용하여 제어를 더 추상적으로 사용하도록 권장하므로, 제어에 관해서는 약간의 이점을 얻게 됩니다.

또한 많은 함수형 언어들에는 동시성에 대한 버전도 있으며, 이 언어들이 일반적으로 '상태'를 피하는 방식이라는 사실 덕분에 동시성 측면에서 이점을 얻을 수 있습니다(예를 들어 순수한 함수형 언어에서는 함수의 모든 인수를 병렬로 평가해도 안전합니다).

5.2.3 Kinds of State

상태의 종류

In most of this paper when we refer to “state” what we really mean is mutable state.

이 페이퍼에서 사용하는 '상태(state)'라는 용어는, '변경 가능한 상태(mutable state)'를 의미합니다.

In languages which do not support (or discourage) mutable state it is common to achieve somewhat similar effects by means of passing extra parameters to procedures (functions). Consider a procedure which performs some internal stateful computation and returns a result — perhaps the procedure implements a counter and returns an incremented value each time it is called:

변경 가능한 상태(mutable state)를 지원하지 않거나 권장하지 않는 언어에서는 프로시저(함수)에 추가 매개변수를 전달하는 방식으로 비슷한 효과를 얻는 것이 일반적입니다.

내부적으로 상태를 갖는 계산을 수행하고 결과를 반환하는 프로시저를 생각해 봅시다. 다음의 프로시저는 카운터를 구현하고 호출될 때마다 증가된 값을 반환합니다.

procedure int getNextCounter() // ’counter’ is declared and initialized elsewhere in the code counter := counter + 1 return counter

The way that this is typically implemented in a basic functional programming language is to replace the stateful procedure which took no arguments and returned one result with a function which takes one argument and returns a pair of values as a result.

기본적인 함수형 프로그래밍 언어에서 이런 프로시저를 구현하는 일반적인 방법은, '인수를 받지 않고 하나의 결과를 리턴하는 상태를 갖는 프로시저'(위의 예제)를, '인수를 하나 받고 두 개의 값을 리턴하는 함수'로 대체하는 것입니다.

function (int,int) getNextCounter(int oldCounter)

let int result = oldCounter + 1

let int newCounter = oldCounter + 1

return (newCounter, result)

There is then an obligation upon the caller of the function to make sure that the next time the

getNextCounterfunction gets called it is supplied with thenewCounterreturned from the previous invocation. Effectively what is happening is that the mutable state that was hidden inside thegetNextCounterprocedure is replaced by an extra parameter on both the input and output of thegetNextCounterfunction. This extra parameter is not mutable in any way (the entity which is referred to byoldCounteris a different value each time the function is called).

이렇게 하면, 함수 호출자는 다음번에 getNextCounter 함수를 호출할 때, 이전 호출의 리턴값으로 받은 newCounter를 인수로 전달해야 합니다.

즉, getNextCounter 프로시저 내부에 숨겨져 있었던 변경 가능한 상태가 getNextCounter 함수의 입력과 출력 모두에서 추가 매개변수로 대체된 것입니다.

이런 추가 매개변수는 어떤 방식으로도 변경할 수 없습니다(oldCounter가 참조하는 엔티티는 함수가 호출될 때마다 다른 값입니다).

As we have discussed, the functional version of this program is referentially transparent, and the imperative version is not (hence the caller of the

getNextCounterprocedure has no idea what may influence the result he gets — it could in principle be dependent upon many, many different hidden mutable variables — but the caller of thegetNextCounterfunction can instantly see exactly that the result can depend only on the single value supplied to the function).

앞에서 설명했듯이, 이 프로그램의 함수 버전은 참조 투명성(referential transparency)을 갖고 있지만, 명령형 버전은 참조 투명성을 갖고 있지 않습니다.

getNextCounter 프로시저를 호출하는 쪽에서는 어떤 것이 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있는지를 알 수 없으며, 이론적으로는 수많은 숨겨진 mutable 변수에 따라 결과가 달라질 수 있습니다.

하지만 getNextCounter 함수의 호출자 입장에서는 함수에 전달하는 단일 값에만 결과가 의존한다는 것을 즉시 알 수 있습니다.

Despite this, the fact is that we are using functional values to simulate state. There is in principle nothing to stop functional programs from passing a single extra parameter into and out of every single function in the entire system. If this extra parameter were a collection (compound value) of some kind then it could be used to simulate an arbitrarily large set of mutable variables. In effect this approach recreates a single pool of global variables — hence, even though referential transparency is maintained, ease of reasoning is lost (we still know that each function is dependent only upon its arguments, but one of them has become so large and contains irrelevant values that the benefit of this knowledge as an aid to understanding is almost nothing). This is however an extreme example and does not detract from the general power of the functional approach.

그럼에도 불구하고 우리는 함수형 값을 사용해 '상태'를 시뮬레이션하고 있는 것이 사실입니다. 원칙적으로는 함수형 프로그램에서 전체 시스템의 모든 함수에 하나의 추가 매개변수를 전달하는 것을 막을 수 있는 방법은 없습니다. 이러한 추가 매개변수가 어떤 종류의 컬렉션(복합 값)이라면, 이를 사용해 임의로 큰 크기의 mutable 변수 집합을 시뮬레이션할 수도 있습니다.

사실상 이 접근 방식은 하나의 전역 변수 풀을 다시 생성하게 되므로, 참조 투명성은 유지되지만 추론의 용이성은 손실됩니다(각 함수가 그 인자에만 의존한다는 것은 여전히 알고 있지만, 그 추가 매개변수가 너무 커져서 불필요한 값들을 포함하게 되기 때문입니다. 이러한 것은 이해를 돕는다는 측면의 장점을 거의 없애버립니다).

그러나 이것은 극단적인 사례이며, 함수형 접근법의 일반적인 효과를 떨어뜨리는 것은 아닙니다.

It is worth noting in passing that — even though it would be no substitute for a guarantee of referential transparency — there is no reason why the functional style of programming cannot be adopted in stateful languages (i.e. imperative as well as impure functional ones). More generally, we would argue that — whatever the language being used — there are large benefits to be had from avoiding hidden, implicit, mutable state.

참조 투명성 보장을 대체할 수는 없지만, statueful 언어(명령형, 순수하지 못한 함수형)에서 함수형 프로그래밍 스타일을 채택하지 못할 이유가 없다는 점은 언급해 둘 가치가 있습니다. 더 일반적으로는, 어떤 프로그래밍 언어를 사용하건 간에 암시적이고 변경 가능한 숨겨진 상태를 피함으로써 얻을 수 있는 이점이 크다고 주장할 수 있겠습니다.

5.2.4 State and Modularity

상태와 모듈성

It is sometimes argued (e.g. [vRH04, p315]) that state is important because it permits a particular kind of modularity. This is certainly true. Working within a stateful framework it is possible to add state to any component without adjusting the components which invoke it. Working within a functional framework the same effect can only be achieved by adjusting every single component that invokes it to carry the additional information around (as with the

getNextCounterfunction above).

상태는 특정 유형의 모듈성을 허용하기 때문에 중요하다는 주장이 있습니다. 그 주장은 확실한 사실입니다.

상태 기반 프레임워크 내에서 작업을 하면, 상태를 호출하는 컴포넌트를 조정하지 않고도 모든 컴포넌트에 상태를 추가할 수 있습니다.

그러나 함수형 프레임워크 내에서 작업할 때는 위의 getNextCounter 함수처럼, 추가 정보를 전달하기 위해 호출하는 모든 컴포넌트를 조정해야만 동일한 효과를 얻을 수 있습니다.

There is a fundamental trade off between the two approaches. In the functional approach (when trying to achieve state-like results) you are forced to make changes to every part of the program that could be affected (adding the relevant extra parameter), in the stateful you are not.

두 접근 방식 사이에는 근본적인 트레이드 오프가 있습니다. 함수형 접근방식에서는 (state기반 방식과 유사한 결과를 얻으려 한다면) 영향을 받을 수 있는 프로그램의 모든 부분을 변경(관련된 부가적인 매개변수를 추가)해야 하지만, 상태 기반(stateful) 방식에서는 그렇지 않습니다.

But what this means is that in a functional program you can always tell exactly what will control the outcome of a procedure (i.e. function) simply by looking at the arguments supplied where it is invoked. In a stateful program this property (again a consequence of referential transparency) is completely destroyed, you can never tell what will control the outcome, and potentially have to look at every single piece of code in the entire system to determine this information.

하지만 함수형 접근방식의 의미는, 함수형 프로그램에서는 프로시저(함수) 호출시에 제공되는 인자를 살펴보면 어떤 것이 프로시저의 결과를 제어하는지에 대해 항상 정확히 알 수 있다는 것에 있습니다.

상태 기반 프로그램에서는 이러한 속성(참조 투명성의 결과)이 완전히 파괴됩니다. 따라서 무엇이 결과를 제어하는지 알기 어려우며, 이 정보를 파악하기 위해 전체 시스템의 모든 코드를 살펴봐야 할 수도 있습니다.

The trade-off is between complexity (with the ability to take a shortcut when making some specific types of change) and simplicity (with huge improvements in both testing and reasoning).

이 트레이드 오프는 복잡성(특정 유형의 변경을 수행할 때 지름길을 선택할 수 있는 능력)과 단순성(테스트와 추론이 모두 크게 향상됨) 사이에 있습니다.

As with the discipline of (static) typing, it is trading a one-off up-front cost for continuing future gains and safety (“one-off” because each piece of code is written once but is read, reasoned about and tested on a continuing basis).

(정적) 타이핑의 규칙과 마찬가지로, 일회성의 초기 비용을 미래의 지속적인 이득과 안전성을 위해 교환하는 것입니다. ("일회성"이라 표현한 것은 각 코드 조각이 한 번만 작성되지만 지속적으로 읽히고, 추론의 대상이 되고, 테스트되기 때문입니다.)

A further problem with the modularity argument is that some examples — such as the use of procedure (function) invocation counts for debugging / performance-tuning purposes — seem to be better addressed within the supporting infrastructure / language, rather than within the system itself (we prefer to advocate a clear separation between such administrative/diagnostic information and the core logic of the system).

(상태가 특정 유형의 모듈성을 가능하게 한다는 내용의) '모듈화 주장'의 또 다른 문제점은 디버깅/성능 튜닝을 위한 프로시저(함수) 호출 횟수를 사용하는 것 같은 일부 사례는, 시스템 자체보다는 지원하는 인프라/언어 내에서 더 잘 해결될 수 있다는 것입니다(우리는 이런 관리/진단 정보와 시스템의 핵심 로직을 명확하게 분리하는 것을 선호합니다).

Still, the fact remains that such arguments have been insufficient to result in widespread adoption of functional programming. We must therefore conclude that the main weakness of functional programming is the flip side of its main strength — namely that problems arise when (as is often the case) the system to be built must maintain state of some kind.

그러나, 함수형 프로그래밍이 널리 받아들여지지 않았다는 사실은 여전히 변하지 않습니다. 이런 점에서 우리는 함수형 프로그래밍의 가장 큰 장점이 동시에 가장 큰 단점이라는 결론을 내릴 수밖에 없습니다. 바로 시스템이 (자주 그렇듯이) 어떤 형태의 상태를 유지해야 한다면 함수형 프로그래밍의 개념에서는 문제가 발생한다는 것입니다.

The question inevitably arises of whether we can find some way to “have our cake and eat it”. One potential approach is the elegant system of monads used by Haskell [Wad95]. This does basically allow you to avoid the problem described above, but it can very easily be abused to create a stateful, side-effecting sub-language (and hence re-introduce all the problems we are seeking to avoid) inside Haskell — albeit one that is marked by its type. Again, despite their huge strengths, monads have as yet been insucient to give rise to widespread adoption of functional techniques.

그렇다면 "두 마리 토끼를 잡을 수 있는" 방법이 있는지에 대한 질문이 불가피하게 제기됩니다.

한 가지 잠재성 있는 접근 방식은 Haskell에서 사용하는 우아한 monad 시스템입니다. monad 시스템은 기본적으로 위에서 설명한 문제를 피할 수 있습니다. 그러나 Haskell 에서는 이 기법을 악용해 타입을 통해 표시되는, 상태 기반의 부작용이 있는 서브 언어(stateful, side-effecting sub-language)를 쉽게 만들어 낼 수 있으며, 우리가 피하려고 하는 모든 문제를 다시 도입할 수도 있습니다. 다시 말하지만, monad 시스템 같은 엄청난 장점이 있는데도 불구하고 아직까지 함수형 기법은 널리 받아들여지게 하는 데에는 부족함이 있습니다.

5.2.5 Summary - Functional Programming

요약 - 함수형 프로그래밍

Functional programming goes a long way towards avoiding the problems of state-derived complexity. This has very significant benefits for testing (avoiding what is normally one of testing’s biggest weaknesses) as well as for reasoning.

함수형 프로그래밍은 상태 기반 복잡성의 문제를 피하는 데에 큰 도움이 됩니다.

이는 테스트에 대해 매우 중요한 장점을 가져다 주며(테스팅의 가장 큰 약점 중 하나를 피하는 데에 도움이 됩니다), 추론에도 도움이 됩니다.

5.3 Logic Programming

Together with functional programming, logic programming is considered to be a declarative style of programming because the emphasis is on specifying what needs to be done rather than exactly how to do it. Also as with functional programming — and in contrast with OOP — its principles and the way of thinking encouraged do not derive from the stateful von-Neumann architecture.

함수형 프로그래밍과 논리 프로그래밍은 선언형 프로그래밍 스타일로 간주할 수 있습니다. 왜냐하면 이 둘은 '정확한 수행 방법'이 아니라 '수행하고 싶은 작업'을 명시하는 데에 중점을 두기 때문입니다.

또한 함수형 프로그래밍과 마찬가지로(OOP와는 달리) 논리 프로그래밍의 원칙과 권장되는 사고 방식은 '상태 기반의 von-Neumann 아키텍처'에서 유래한 것이 아니라는 특징이 있습니다.

Pure logic programming is the approach of doing nothing more than making statements about the problem (and desired solutions). This is done by stating a set of axioms which describe the problem and the attributes required of something for it to be considered a solution. The ideal of logic programming is that there should be an infrastructure which can take the raw axioms and use them to find or check solutions. All solutions are formal logical consequences of the axioms supplied, and “running” the system is equivalent to the construction of a formal proof of each solution.

순수한 논리 프로그래밍은 문제와 원하는 해답에 대한 명제만을 작성하는 접근 방식입니다. 이는 문제를 설명하고 해답을 얻기 위해 요구되는 속성들을 명시하는 일련의 공리(axiom)를 세우는 것으로 이루어집니다. 논리 프로그래밍의 이상적인 모델은 이러한 기본이 되는 공리들을 적용해 해결책을 찾거나 검증할 수 있는 인프라를 갖춰야 한다는 것입니다. 모든 해답은 제공된 공리들을 통한 형식적 논리의 결과이며, 시스템을 '실행'한다는 것은 각 해답에 대한 형식적인 증명을 구성하는 것과 동일합니다.

The seminal “logic programming” language was Prolog. Prolog is best seen as a pure logical core (pure Prolog) with various extra-logical extensions.6 Pure Prolog is close to the ideals of logic programming, but there are important differences. Every pure Prolog program can be “read” in two ways — either as a pure set of logical axioms (i.e. assertions about the problem domain — this is the pure logic programming reading), or operationally — as a sequence of commands which are applied (in a particular order) to determine whether a goal can be deduced (from the axioms). This second reading corresponds to the actual way that pure Prolog will make use of the axioms when it tries to prove goals. It is worth noting that a single Prolog program can be both correct when read in the first way, and incorrect (for example due to non-termination) when read in the second.

"논리 프로그래밍"의 기원은 Prolog입니다. Prolog는 순수한 논리적 핵심(pure logical core)에 다양한 추가적인 논리 확장6이 결합된 형태로 이해하는 것이 가장 바람직합니다. 순수한 Prolog는 논리 프로그래밍의 이상에 가깝지만, 중요한 차이점이 있습니다.

모든 순수한 Prolog 프로그램은 두 가지 방법으로 해석할 수 있습니다.

- 순수한 논리적 공리들의 집합(즉, 문제 도메인에 대한 주장(assertions))

- 순수한 논리 프로그래밍으로 Prolog 프로그램을 해석하는 방식.

- 공리로부터 목표를 추론할 수 있는지를 결정하기 위해 (특정한 순서로) 적용하는 명령어들의 시퀀스.

- 작동방식을 기준으로 Prolog 프로그램을 해석하는 방식.

두 번째 해석 방식은 순수한 Prolog가 공리들을 활용하여 목표를 입증하려고 시도할 때의 실제 작동 방식에 해당합니다.

하나의 Prolog 프로그램은 첫 번째 해석 방식으로 보면 논리적으로 모순이 없을 수 있지만, 두 번째 해석 방식으로 볼 때에는 (예를 들어 무한 루프 등으로 인해) 잘못된 프로그램일 수 있다는 점을 주목해야 합니다.

It is for this reason that Prolog falls short of the ideals of logic programming. Specifically it is necessary to be concerned with the operational interpretation of the program whilst writing the axioms.

Prolog가 논리 프로그래밍의 이상적인 지점에 도달하지 못하는 이유가 바로 여기에 있습니다. 공리를 작성하는 동안에도 프로그램의 작동 방식에 주의를 기울여야 한다는 점이 문제입니다.

5.3.1 State

상태

Pure logic programming makes no use of mutable state, and for this reason profits from the same advantages in understandability that accrue to pure functional programming. Many languages based on the paradigm do however provide some stateful mechanisms. In the extra-logical part of Prolog for example there are facilities for adjusting the program itself by adding new axioms for example. Other languages such as Oz (which has its roots in logic programming but has been extended to become “multi-paradigm”) provide mutable state in a traditional way — similar to the way it is provided by impure functional languages.

순수한 논리 프로그래밍은 변경 가능한 상태(mutable state)를 전혀 사용하지 않으므로, 순수한 함수형 프로그래밍과 같이 '이해'하기 용이하다는 장점을 누리게 됩니다.

그러나 논리 패러다임에 기반한 많은 언어들은 상태 기반 메커니즘도 제공합니다. 예를 들어 Prolog의 논리 확장 부분에서는 새로운 공리를 추가하여 프로그램 자체를 조정할 수 있는 기능이 있습니다. (논리 프로그래밍에 뿌리를 두고 있지만 "다중 패러다임"으로 확장된) Oz 프로그래밍 언어와 같은 다른 언어들은, 순수하지 않은 함수형 언어에서 제공하는 방식과 유사하게 '변경 가능한 상태'를 제공합니다.

All of these approaches to state sacrifice referential transparency and hence potentially suffer from the same drawbacks as imperative languages in this regard. The one advantage that all these impure non-von-Neumann derived languages can claim is that — whilst state is permitted its use is generally discouraged (which is in stark contrast to the stateful von-Neumann world). Still, without purity there are no guarantees and all the same state-related problems can sometimes occur.

이런 종류의 상태 관리 접근법은 참조 투명성을 희생하므로, 이 관점에서 명령형 언어와 같은 단점을 갖게 됩니다. 이런 식의 순수하지 않은 'non-폰 노이만' 파생 언어들이 주장하는 것은, 상태의 사용을 허용하긴 하지만 권장은 하지 않는다는 것입니다. (이는 상태 중심으로 돌아가는 폰 노이만 세계와는 대조적인 점입니다.) 그러나 순수성이 없기 때문에 어떤 것도 보장할 수 없으며 때때로 상태 관련 문제가 발생할 수 있습니다.

5.3.2 Control

제어

In the case of pure Prolog the language specifies both an implicit ordering for the processing of sub-goals (left to right), and also an implicit ordering of clause application (top down) — these basically correspond to an operational commitment to process the program in the same order as it is read textually (in a depth first manner). This means that some particular ways of writing down the program can lead to non-termination, and — when combined with the fact that some extra-logical features of the language permit side-effects — leads inevitably to the standard difficulty for informal reasoning caused by control flow. (Note that these reasoning difficulties do not arise in ideal world of logic programming where there simply is no specified control — as distinct from in pure Prolog programming where there is).

순수한 Prolog의 경우, 프로그래밍 언어는 하위 목표(sub-goal)의 처리 순서(왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로)와 절(clause) 적용에 대한 순서(위에서 아래로)를 모두 암묵적으로 지정합니다.

이는 기본적으로 프로그램이 텍스트로 읽힐 때와 같은 순서로(깊이 우선 방식) 처리하도록 약속하는 방식과 같습니다. 이것은, 특정한 방식으로 프로그램을 작성하면 비종료(non-termination)를 유발할 수 있다는 것으로 연결됩니다. 이 사실은 언어의 일부 비논리적 특징이 '부작용(side-effect)'을 허용한다는 사실과 결합되어, 결국 '제어 흐름' 때문에 '비형식적 추론'이 어려워지는 문제를 피할 수 없게 됩니다.

(이렇게 추론이 어려워지는 문제는 제어를 전혀 지정하지 않는 이상적인 논리 프로그래밍의 세계에서는 발생하지 않습니다. 이는 순수한 Prolog 프로그래밍과는 달리, 그 외의 언어들에서는 제어 흐름을 지정하기 때문입니다.)

As for Prolog’s other extra-logical features, some of them further widen the gap between the language and logic programming in its ideal form. One example of this is the provision of “cuts” which offer explicit restriction of control flow. These explicit restrictions are intertwined with the pure logic component of the system and inevitably have an adverse affect on attempts to reason about the program (misunderstandings of the effects of cuts are recognised to be a major source of bugs in Prolog programs [SS94, p190]).

Prolog의 다른 논리 확장 기능들은, 프로그래밍 언어와 이상적인 형태의 논리 프로그래밍 사이의 격차를 더욱 넓히는데 일조합니다.

한 가지 예를 들자면, 제어 흐름을 명시적으로 제한하는 "cuts" 기능을 들 수 있습니다. 이러한 명시적인 제한은 시스템의 순수한 논리적 컴포넌트와 얽혀 있어, 프로그램에 대한 추론을 시도할 때 불리한 영향을 미칩니다. (cut의 효과에 대한 오해는 Prolog 프로그램의 주요 버그 원인으로 인식되고 있습니다.)

It is worth noting that some more modern languages of the logic programming family offer more flexibility over control than the implicit depth-first search used by Prolog. One example would be Oz which offers the ability to program specific control strategies which can then be applied to different problems as desired. This is a very useful feature because it allows significant explicit control flexibility to be specified separately from the main program (i.e. without contaminating it through the addition of control complexity).

논리 프로그래밍 계열의 최신 언어들 중 어떤 것들은 Prolog에서 사용하는 '암시적 깊이 우선' 탐색보다 더 유연한 제어를 제공한다는 점에 주목할 필요가 있습니다.

한 가지 예로, Oz가 있습니다. Oz는 특정한 제어 전략을 프로그래밍할 수 있도록 하여, 원하는 대로 다른 문제에 적용할 수 있습니다. 이는 메인 프로그램과 별도로 (즉, 제어 복잡성을 추가하여 프로그램을 오염시키지 않고) 상당히 명시적인 제어 유연성을 지정할 수 있기 때문에 매우 유용한 기능입니다.

5.3.3 Summary — Logic Programming

요약 - 논리 프로그래밍

One of the most interesting things about logic programming is that (despite the limitations of some actual logic-based languages) it offers the tantalising promise of the ability to escape from the complexity problems caused by control.

논리 프로그래밍의 가장 흥미로운 점 하나는 (몇몇 로직 기반 언어들의 한계에도 불구하고) 제어로 인한 복잡성 문제에서 벗어날 수 있다는 매력적인 가능성을 제공한다는 것입니다.

6 Accidents and Essence

우발적 복잡성과 본질적 복잡성

Brooks defined difficulties of “essence” as those inherent in the nature of software and classified the rest as “accidents”.

We shall basically use the terms in the same sense — but prefer to start by considering the complexity of the problem itself before software has even entered the picture. Hence we define the following two types of complexity:

[[/people/fred-brooks]]{Brooks}는 소프트웨어의 본질에 내재된 어려움을 "본질적" 어려움으로 정의하고, 나머지를 "우발적" 어려움으로 분류했습니다.

우리는 기본적으로 그와 같은 의미의 용어를 사용할 것입니다. 그러나 소프트웨어라는 틀에 대해 논의하기 전에 문제 자체의 복잡성을 고려하는 것으로 시작하고자 합니다. 따라서 우리는 다음 두 가지 유형의 복잡성을 정의합니다.

Essential Complexity is inherent in, and the essence of, the problem (as seen by the users).

Accidental Complexity is all the rest — complexity with which the development team would not have to deal in the ideal world (e.g. complexity arising from performance issues and from suboptimal language and infrastructure).

- 본질적 복잡성

- 문제의 본질에 내재되어 있으며, 사용자 관점에서 중요한 복잡성.

- 우발적 복잡성

- 본질적 복잡성이 아닌 모든 복잡성.

- 이상적인 세계에서는 개발팀이 처리할 필요가 없는 복잡성

- (예: 성능 문제와 최적화되지 않은 언어와 인프라에서 발생하는 복잡성)을 의미.

Note that the definition of essential is deliberately more strict than common usage. Specifically when we use the term essential we will mean strictly essential to the users’ problem (as opposed to — perhaps — essential to some specific, implemented, system, or even — essential to software in general). For example — according to the terminology we shall use in this paper — bits, bytes, transistors, electricity and computers themselves are not in any way essential (because they have nothing to do with the users’ problem).

'본질적'이라는 용어를 의도적으로 일반적인 사용법보다 더 엄격하게 정의했다는 점에 주목해야 합니다. 특히 '본질적'이라는 용어를 사용할 때는 엄격하게 '사용자의 문제에 본질적'이라는 의미로 사용할 것입니다. 구현된 특정 시스템에 본질적이거나, 심지어 소프트웨어 전반에 본질적이라는 의미가 아닙니다. 예를 들어 이 논문에서 사용하는 용법을 적용하면 비트, 바이트, 트랜지스터, 전기, 컴퓨터 자체는 사용자의 문제와 관련이 없으므로 어떤 방식으로도 '본질적'이지 않습니다.

Also, the term “accident” is more commonly used with the connotation of “mishap”. Here (as with Brooks) we use it in the more general sense of “something non-essential which is present”.

또한, "우발적"이라는 용어는 "실수"라는 의미로 사용되는 경우가 더 흔합니다. 여기에서는 [[/people/fred-brooks]]{Brooks}와 마찬가지로 "이미 존재하는 비본질적인 무언가"이라는 다소 일반적인 의미로 사용합니다.

In order to justify these two definitions we start by considering the role of a software development team — namely to produce (using some given language and infrastructure) and maintain a software system which serves the purposes of its users. The complexity in which we are interested is the complexity involved in this task, and it is this which we seek to classify as accidental or essential. We hence see essential complexity as “the complexity with which the team will have to be concerned, even in the ideal world”.

우리의 이 두 가지 용어 정의를 정당화하기 위해 소프트웨어 개발팀의 역할을 고려해 본다면, '소프트웨어 개발팀'의 역할은 주어진 언어와 인프라를 사용하여 사용자의 목적을 달성하는 소프트웨어 시스템을 생성(생산)하고 유지하는 것이라 할 수 있습니다.

우리가 관심을 갖는 종류의 복잡성은 바로 이러한 작업에 포함된 복잡성이며, 이런 복잡성을 '우발적 복잡성'과 '본질적 복잡성'으로 분류하고자 합니다. 그리고 우리는 본질적인 복잡성을 "이상적인 세계에서도 팀이 신경써야 할 복잡성"으로 정의합니다.

Note that the “have to” part of this observation is critical — if there is any possible way that the team could produce a system that the users will consider correct without having to be concerned with a given type of complexity then that complexity is not essential.

여기에서 "신경써야 할" 부분이 매우 중요합니다. 팀이 특정한 유형의 복잡성에 신경을 쓰지 않고도 '사용자가 올바르다고 인정할 수 있는 시스템'을 만들 수 있다면, 그 복잡성은 본질적인 것이라 할 수 없습니다.

Given that in the real world not all possible ways are practical, the implication is that any real development will need to contend with some accidental complexity. The definition does not seek to deny this — merely to identify its secondary nature.

실제 세계에서 실제로 가능한 방법이라 해서 모두 실용적인 방법인 것이 아니라는 점을 감안하면, 어떠한 실제적인 개발 활동에서도 어느 정도의 우발적 복잡성을 다루어야 할 것입니다. '우발적 복잡성'의 정의는 이런 사실을 부정하려는 것이 아니라, 그것이 부차적인 성격을 갖고 있다는 점을 드러내려는 것입니다.

Ultimately (as we shall see below in section 7) our definition is equivalent to saying that what is essential to the team is what the users have to be concerned with. This is because in the ideal world we would be using language and infrastructure which would let us express the users’ problem directly without having to express anything else — and this is how we arrive at the definitions given above.

(7장에서 살펴보겠지만) 우리의 용어 정의는 결국 '팀에게 본질적인 것'이란 곧 '사용자의 관심사'라고 말하는 것과 마찬가지입니다. 이상적인 세계에서는 사용자의 문제를 직접 표현할 수 있는 언어와 인프라를 사용할 수 있을 것이므로, 앞에서 제시한 정의에 자연스럽게 도달하게 될 것입니다.

The argument might be presented that in the ideal world we could just find infrastructure which already solves the users’ problem completely. Whilst it is possible to imagine that someone has done the work already, it is not particularly enlightening — it may be best to consider an implicit restriction that the hypothetical language and infrastructure be general purpose and domain-neutral.

이상적인 세계에서는 이미 '사용자의 문제를 완전히 해결하는 인프라'가 존재한다는 주장이 있을 수 있습니다.

누군가가 이런 작업을 이미 수행했다고 상상할 수는 있습니다. 하지만 별로 도움이 되는 상상은 아닙니다. 이상적인 언어와 인프라가 범용적이고 도메인 중립적이어야 한다는 암묵적인 제약을 갖는다는 가정을 고려하는 것이 좋을 것입니다.

One implication of this definition is that if the user doesn’t even know what something is (e.g. a thread pool or a loop counter — to pick two arbitrary examples) then it cannot possibly be essential by our definition (we are assuming of course — alas possibly with some optimism — that the users do in fact know and understand the problem that they want solved).

이 정의의 한 가지 의의는 '사용자가 뭔지 전혀 모르고 있는 대상'이 있다면(예를 들어 스레드 풀이나 루프 카운터와 같은 것들), 우리의 정의에 따라서 그것은 본질적인 것이 아니게 된다는 것입니다. (물론 우리는 사용자가 해결하고자 하는 문제를 알고 잘 이해하고 있다고 - 가능한 한 긍정적으로 - 가정하고 있습니다.)

Brooks asserts [Bro86] (and others such as Booch agree [Boo91]) that “The complexity of software is an essential property, not an accidental one”. This would suggest that the majority (at least) of the complexity that we find in contemporary large systems is of the essential type.

Brooks는 "소프트웨어의 복잡성은 우발적인 것이 아니라 본질적인 것이다"라고 주장합니다. (그리고 Booch와 같은 다른 사람들도 이에 동의합니다.) Brooks의 주장은 현대적인 대규모 시스템에서 발견되는 복잡성의 대부분이 본질적인 복잡성이라는 것을 시사합니다.

We disagree. Complexity itself is not an inherent (or essential) property of software (it is perfectly possible to write software which is simple and yet is still software), and further, much complexity that we do see in existing software is not essential (to the problem). When it comes to accidental and essential complexity we firmly believe that the former exists and that the goal of software engineering must be both to eliminate as much of it as possible, and to assist with the latter.

그러나 우리는 [[/people/fred-brooks]]{Brooks}의 주장에 동의하지 않습니다. 복잡성 자체는 소프트웨어의 고유한(본질적인) 속성이 아닙니다. (단순한 소프트웨어를 작성하는 것 자체는 완벽하게 가능합니다.) 또한, 기존 소프트웨어에서 발견되는 복잡성의 대부분은 (문제에 대해) 본질적인 것이 아닙니다.

우리는 우발적 복잡성이 존재한다는 것을 인정하고, 본질적 복잡성을 다루는 일에 도움을 주며, 가능한 한 많은 우발적 복잡성을 제거하는 것이 소프트웨어 공학의 목표가 되어야 한다고 확신합니다.

Because of this it is vital that we carefully scrutinize accidental complexity. We now attempt to classify occurrences of complexity as either accidental or essential.

따라서 우발적인 복잡성을 주의 깊게 조사하는 것이 매우 중요합니다. 이제 우리는 우발적인 복잡성과 본질적인 복잡성으로 복잡성의 발생 사례를 분류하고자 합니다.

7 Recommended General Approach

권장하는 일반적인 접근 방법

Given that our main recommendations revolve around trying to avoid as much accidental complexity as possible, we now need to look at which bits of the complexity must be considered accidental and which essential.

우리의 주요 권장 사항은 우발적인 복잡성을 가능한 한 많이 피하려는 방향을 중심으로 하고 있습니다. 따라서 이제 복잡성의 어떤 부분이 우발적이고, 어떤 부분이 본질적인 것으로 파악해야 하는지 살펴보아야 합니다.

We shall answer this by considering exactly what complexity could not possibly be avoided even in the ideal world (this is basically how we define essential). We then follow this up with a look at just how realistic this ideal world really is before finally giving some recommendations.

우리는 이상적인 세계에서도 피할 수 없는 복잡성(본질적인 복잡성)이 무엇인지를 정확히 살펴보는 것으로 이 질문에 대해 답하려 합니다. 그런 다음 이상적인 환경이 현실과 얼마나 다른지 살펴보고, 마지막으로 몇 가지 권장 사항을 제시하겠습니다.

7.1 Ideal World

이상적인 세계

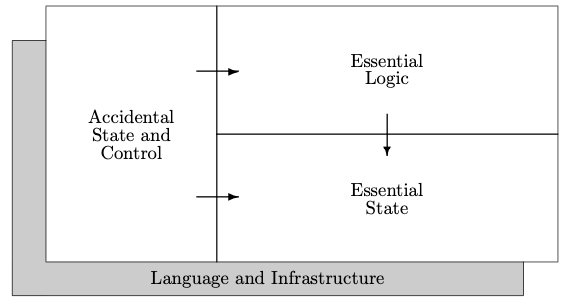

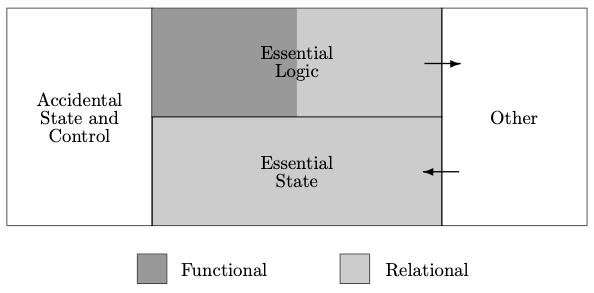

In the ideal world we are not concerned with performance, and our language and infrastructure provide all the general support we desire. It is against this background that we are going to examine state and control. Specifically, we are going to identify state as accidental state if we can omit it in this ideal world, and the same applies to control.

이상적인 세계에서는 성능에 대해 걱정할 필요가 없으며, 프로그래밍 언어와 인프라는 우리가 원하는 모든 것을 제공한다고 합시다. 우리는 이러한 세계를 전제하고 상태와 제어에 대해 살펴볼 것입니다.