Kafka - a Distributed Messaging System for Log Processing

Kafka - 대용량 로그 처리를 위한 분산 메시징 시스템

- Kafka: a Distributed Messaging System for Log Processing 번역

- Links

- 2011년에 LinkedIn에서 발표한 Kafka 논문.

Kafka: a Distributed Messaging System for Log Processing 번역

일러두기

이 웹 사이트( https://johngrib.github.io )는 상업적인 용도로 운영하는 것이 아니며, 나는 개인적인 공부 목적으로 이 논문을 번역합니다. 이 논문의 원본 저작권자에게 존경과 감사를 표합니다.

This website (https://johngrib.github.io) is not operated for commercial purposes, and I have translated this paper for my personal study. I express my respect and gratitude to the original copyright holders of this paper.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page.

To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee.

NetDB'11, Jun. 12, 2011, Athens, Greece.

Copyright 2011 ACM 978-1-4503-0652-2/11/06…$10.00.

- 의역이 많으며, 오역이 상당히 있을 수 있습니다.

- 번역하는 과정에서 OpenAI의 GPT-4의 도움을 받았습니다.

ABSTRACT

초록

Log processing has become a critical component of the data pipeline for consumer internet companies. We introduce Kafka, a distributed messaging system that we developed for collecting and delivering high volumes of log data with low latency. Our system incorporates ideas from existing log aggregators and messaging systems, and is suitable for both offline and online message consumption. We made quite a few unconventional yet practical design choices in Kafka to make our system efficient and scalable. Our experimental results show that Kafka has superior performance when compared to two popular messaging systems. We have been using Kafka in production for some time and it is processing hundreds of gigabytes of new data each day.

로그 처리는 소비자 중심 인터넷 기업의 데이터 파이프라인에서 핵심적인 구성 요소가 되었습니다. 이 글에서는 우리가 개발한 Kafka를 소개하고자 합니다. Kafka는 낮은 시연 시간으로 대량의 로그 데이터를 수집하고 전달하기 위한 분산 메시징 시스템입니다. 우리의 시스템은 기존의 로그 집계기와 메시징 시스템의 아이디어를 통합하고 있으며, 오프라인과 온라인 양쪽의 메시징 소비에 적합합니다. 우리는 카프카에서 효율적이고 확장 가능한 시스템을 만들기 위해, 일반적이지는 않지만 실용적인 몇 가지 선택을 했습니다. 우리의 실험 결과를 보면, 카프카는 두 가지 인기 있는 메시징 시스템과 비교해 보았을 때 우수한 성능을 보여줍니다. 우리는 일정 시간 동안 카프카를 프로덕션 환경에서 사용해 왔고, 매일 수백 기가바이트의 새로운 데이터를 처리하고 있습니다.

General Terms

Management, Performance, Design, Experimentation.

Keywords

messaging, distributed, log processing, throughput, online.

1. Introduction

1. 서론

There is a large amount of “log” data generated at any sizable internet company. This data typically includes (1) user activity events corresponding to logins, pageviews, clicks, “likes”, sharing, comments, and search queries; (2) operational metrics such as service call stack, call latency, errors, and system metrics such as CPU, memory, network, or disk utilization on each machine. Log data has long been a component of analytics used to track user engagement, system utilization, and other metrics. However recent trends in internet applications have made activity data a part of the production data pipeline used directly in site features. These uses include (1) search relevance, (2) recommendations which may be driven by item popularity or cooccurrence in the activity stream, (3) ad targeting and reporting, and (4) security applications that protect against abusive behaviors such as spam or unauthorized data scraping, and (5) newsfeed features that aggregate user status updates or actions for their “friends” or “connections” to read.

규모있는 인터넷 기업에서는 상당한 양의 "로그" 데이터가 생성됩니다. 이러한 데이터는 일반적으로 다음의 내용들로 이루어집니다.

- (1) 사용자 활동 이벤트

- 로그인, 페이지 보기, 클릭, "좋아요", 공유, 댓글 및 검색 쿼리 등.

- (2) 시스템 지표

- 서비스 호출 스택, 호출 지연, 에러.

- 각 머신에서의 CPU, 메모리, 네트워크, 디스크 사용률.

로그 데이터는 사용자 참여, 시스템 사용률 등의 지표를 추적하는 데 사용되는 분석의 구성 요소로 오랫동안 사용되었습니다. 그러나 최근의 인터넷 애플리케이션 트렌드로 인해, 활동 데이터가 사이트의 기능에서 직접 사용되는 프로덕션 데이터 파이프라인의 일부가 되었습니다. 이러한 활동 데이터 사용 사례에는 다음과 같은 것들이 있습니다.

- (1) 검색 관련.

- (2) 활동 스트림에서 아이템의 인기나 동시 발생에 의해 작동하는 '추천'.

- (3) 광고 타겟팅과 광고 보고서.

- (4) 스팸 또는 미승인 데이터 스크래핑과 같은 악성 행위를 방지하는 보안 애플리케이션.

- (5) '사용자 상태 업데이트' 또는 "친구"나 "연결된 사용자들"에게 보여주는 '사용자 상태 업데이트', 행동을 집계하는 뉴스 피드 기능 등.

This production, real-time usage of log data creates new challenges for data systems because its volume is orders of magnitude larger than the “real” data. For example, search, recommendations, and advertising often require computing granular click-through rates, which generate log records not only for every user click, but also for dozens of items on each page that are not clicked. Every day, China Mobile collects 5–8TB of phone call records [11] and Facebook gathers almost 6TB of various user activity events [12].

로그 데이터의 실시간 사용은 "실제" 데이터보다 몇 단계 더 큰 규모의 데이터 볼륨으로, 데이터 시스템에 새로운 도전을 제시합니다.

예를 들어 검색, 추천, 광고는 종종 세부적인 클릭률을 계산해야 하는데, 이는 사용자의 모든 클릭에 대한 로그 레코드뿐만 아니라 클릭되지 않은 각 페이지의 수십 개의 항목에 대한 로그 레코드도 생성합니다. 중국의 모바일은 매일 5-8TB의 전화 기록을 수집하고, 페이스북은 거의 6TB의 다양한 사용자 활동 이벤트를 수집합니다.

Many early systems for processing this kind of data relied on physically scraping log files off production servers for analysis. In recent years, several specialized distributed log aggregators have been built, including Facebook’s Scribe [6], Yahoo’s Data Highway [4], and Cloudera’s Flume [3]. Those systems are primarily designed for collecting and loading the log data into a data warehouse or Hadoop [8] for offline consumption. At LinkedIn (a social network site), we found that in addition to traditional offline analytics, we needed to support most of the real-time applications mentioned above with delays of no more than a few seconds.

이런 종류의 데이터를 처리하기 위한 초기 시스템들은, 분석을 위해 프로덕션 서버에서 물리적으로 로그 파일을 스크래핑하는 방식을 사용했습니다. 최근 몇 년 동안에는 페이스북의 Scribe, 야후의 Data Highway, 클라우데라의 Flume 등과 같은 특수한 분산 로그 수집기들이 개발되었습니다. 이러한 시스템들은 주로 로그 데이터를 수집해서 데이터 웨어하우스 또는 하둡에 적재하고, 오프라인으로 사용하기 위해 설계되었습니다.

링크드인(소셜 네트워크 사이트)에서는 전통적인 오프라인 분석 외에도 위에서 언급한 실시간 애플리케이션 대부분을 몇 초 이내의 지연 시간으로 지원해야 했습니다.

We have built a novel messaging system for log processing called Kafka [18] that combines the benefits of traditional log aggregators and messaging systems. On the one hand, Kafka is distributed and scalable, and offers high throughput. On the other hand, Kafka provides an API similar to a messaging system and allows applications to consume log events in real time. Kafka has been open sourced and used successfully in production at LinkedIn for more than 6 months. It greatly simplifies our infrastructure, since we can exploit a single piece of software for both online and offline consumption of the log data of all types. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We revisit traditional messaging systems and log aggregators in Section 2. In Section 3, we describe the architecture of Kafka and its key design principles. We describe our deployment of Kafka at LinkedIn in Section 4 and the performance results of Kafka in Section 5. We discuss future work and conclude in Section 6.

우리는 전통적인 로그 집계기와 메시징 시스템의 장점을 결합한, Kafka라는 새로운 로그 처리용 메시징 시스템을 구축했습니다. 한편, Kafka는 분산되고 확장 가능하며, 높은 처리량을 제공합니다. 그리고 Kafka는 메시징 시스템과 유사한 API를 제공하며, 애플리케이션에서 실시간으로 로그 이벤트를 소비할 수 있도록 합니다. Kafka는 오픈소스로 공개되었고, 링크드인에서 6개월 이상의 프로덕션 환경에서 성공적으로 사용되고 있습니다. Kafka로 인해 모든 유형의 로그 데이터를 온라인과 오프라인으로 사용하는 데에 사용되는 소프트웨어를 하나로 통합할 수 있었기 때문에, 우리의 인프라가 크게 단순화되었습니다.

이 논문의 나머지 부분은 다음과 같이 되어 있습니다. 섹션 2에서는 전통적인 메시징 시스템과 로그 집계기를 다시 살펴봅니다. 섹션 3에서는 Kafka의 아키텍처와 핵심 설계 원칙을 설명합니다. 섹션 4에서는 링크드인에서의 Kafka 배포를, 섹션 5에서는 Kafka의 성능 결과를 설명합니다. 섹션 6에서는 앞으로의 작업과 결론에 대해 논의합니다.

2. Related Work

2. 관련된 연구

Traditional enterprise messaging systems [1][7][15][17] have existed for a long time and often play a critical role as an event bus for processing asynchronous data flows. However, there are a few reasons why they tend not to be a good fit for log processing. First, there is a mismatch in features offered by enterprise systems. Those systems often focus on offering a rich set of delivery guarantees. For example, IBM Websphere MQ [7] has transactional supports that allow an application to insert messages into multiple queues atomically. The JMS [14] specification allows each individual message to be acknowledged after consumption, potentially out of order. Such delivery guarantees are often overkill for collecting log data. For instance, losing a few pageview events occasionally is certainly not the end of the world. Those unneeded features tend to increase the complexity of both the API and the underlying implementation of those systems. Second, many systems do not focus as strongly on throughput as their primary design constraint. For example, JMS has no API to allow the producer to explicitly batch multiple messages into a single request. This means each message requires a full TCP/IP roundtrip, which is not feasible for the throughput requirements of our domain. Third, those systems are weak in distributed support. There is no easy way to partition and store messages on multiple machines. Finally, many messaging systems assume near immediate consumption of messages, so the queue of unconsumed messages is always fairly small. Their performance degrades significantly if messages are allowed to accumulate, as is the case for offline consumers such as data warehousing applications that do periodic large loads rather than continuous consumption.

전통적인 기업용 메시징 시스템들은 오랫동안 존재해 왔으며, 비동기 데이터 흐름을 처리하는 이벤트 버스로서 종종 중요한 역할을 담당합니다. 그러나 그러한 시스템들이 로그 처리에 적합하지 않은 이유가 몇 가지 있습니다.

첫째, 기업용 시스템에서 제공하는 기능들 간의 불일치가 있습니다. 이러한 시스템들은 종종 다양한 전달 보장을 제공하는데 집중합니다. 예를 들어, IBM Websphere MQ는 애플리케이션이 여러 큐에 메시지를 원자적으로 입력할 수 있도록 해주는 트랜잭션을 지원합니다. JMS 명세는 소비 후 각각의 메시지를 순서에 상관없이 확인할 수 있도록 해줍니다. 이러한 전달 보장은 로그 데이터 수집에 대해서는 과도한 기능입니다. 가령, 가끔 페이지뷰 이벤트를 몇 개 잃어버린다 해도 세상이 끝장나는 것은 아니기 때문입니다. 이러한 필요하지 않은 기능들은 API와 시스템의 기본 구현을 복잡하게 만드는 경향이 있습니다.

둘째, 많은 시스템에서는 처리율을 설계의 핵심 제약조건으로 강하게 주목하지 않습니다. 예를 들어 JMS에는, 프로듀서가 여러 메시지를 하나의 요청으로 명시적으로 묶을 수 있는 API가 없습니다. 이는 각 메시지가 전체 TCP/IP 라운드트립을 필요로 한다는 것을 의미하며, 이런 것은 우리 도메인의 처리율 요구사항에는 적합하지 않습니다.

셋째, 이러한 시스템들은 분산 지원이 약합니다. 여러 대의 컴퓨터에 메시지를 분할하고 저장하는 것은 쉽지 않습니다. 마지막으로, 많은 메시징 시스템들은 메시지 소비가 거의 즉시라고 가정하기 때문에, 항상 소비되지 않은 메시지의 큐가 꽤 작습니다. 연속적인 소비 대신 주기적인 대량 적재를 수행하는 데이터 웨어하우징 애플리케이션과 같은 오프라인 소비자의 경우, 메시지가 쌓이는 것을 허용하면 성능이 크게 저하됩니다.

A number of specialized log aggregators have been built over the last few years. Facebook uses a system called Scribe. Each frontend machine can send log data to a set of Scribe machines over sockets. Each Scribe machine aggregates the log entries and periodically dumps them to HDFS [9] or an NFS device. Yahoo’s data highway project has a similar dataflow. A set of machines aggregate events from the clients and roll out “minute” files, which are then added to HDFS. Flume is a relatively new log aggregator developed by Cloudera. It supports extensible “pipes” and “sinks”, and makes streaming log data very flexible. It also has more integrated distributed support. However, most of those systems are built for consuming the log data offline, and often expose implementation details unnecessarily (e.g. “minute files”) to the consumer. Additionally, most of them use a “push” model in which the broker forwards data to consumers. At LinkedIn, we find the “pull” model more suitable for our applications since each consumer can retrieve the messages at the maximum rate it can sustain and avoid being flooded by messages pushed faster than it can handle. The pull model also makes it easy to rewind a consumer and we discuss this benefit at the end of Section 3.2.

지난 몇 년 동안 수많은 전문적인 로그 집계기가 개발되었습니다.

페이스북은 Scribe라는 시스템을 사용합니다. 각 프론트엔드 머신은 Scribe 머신들에게 소켓을 통해 로그 데이터를 보낼 수 있습니다. 각각의 Scribe 머신은 로그 엔트리들을 집계하고 주기적으로 HDFS나 NFS 장치에 저장합니다.

야후의 데이터 하이웨이 프로젝트도 비슷한 데이터 흐름을 가지고 있습니다. 클라이언트로부터 이벤트를 집계하는 머신 집합이 “minute” 파일을 만들어서 HDFS에 추가합니다.

Flume는 클라우데라에서 개발한 상대적으로 새로운 로그 집계기입니다. 확장 가능한 “pipes”와 “sinks”를 지원하며, 로그 데이터 스트리밍을 매우 유연하게 만들어 줍니다. 또한 더 통합된 분산 지원을 제공합니다.

그러나, 대부분의 이러한 시스템들은 로그 데이터를 오프라인으로 소비하기 위해 만들어졌으며, 종종 불필요한 세부 구현을 컨슈머에게 노출합니다.(예: “minute files”) 게다가 대부분의 시스템에서는 브로커가 데이터를 컨슈머에게 전달하는 “push” 모델을 사용합니다.

링크드인에서는 "pull" 모델이 우리의 애플리케이션에 더 적합하다고 판단합니다. 각각의 컨슈머가 최대 속도로 메시지를 가져올 수 있고, 처리할 수 없는 속도로 메시지가 푸시되는 것을 피할 수 있기 때문입니다. "pull" 모델은 컨슈머를 되감기하는 것을 쉽게 만들어주기도 합니다. 이러한 장점은 3.2절의 끝에서 논의합니다.

More recently, Yahoo! Research developed a new distributed pub/sub system called HedWig [13]. HedWig is highly scalable and available, and offers strong durability guarantees. However, it is mainly intended for storing the commit log of a data store.

최근, Yahoo! Research는 HedWig이라는 새로운 분산 pub/sub 시스템을 개발했습니다. HedWig는 높은 확장성과 가용성을 제공하며, 강력한 내구성 보장을 제공합니다. 그러나, 주로 데이터 스토어의 커밋 로그를 저장하기 위한 목적으로 사용됩니다.

3. Kafka Architecture and Design Principles

Because of limitations in existing systems, we developed a new messaging-based log aggregator Kafka. We first introduce the basic concepts in Kafka. A stream of messages of a particular type is defined by a topic. A producer can publish messages to a topic. The published messages are then stored at a set of servers called brokers. A consumer can subscribe to one or more topics from the brokers, and consume the subscribed messages by pulling data from the brokers.

기존 시스템의 한계 때문에, 우리는 새로운 메시징 기반 로그 집계기인 Kafka를 개발했습니다. 먼저 Kafka의 기본 개념을 소개합니다. 특정한 타입의 메시지 스트림을 토픽으로 정의합니다. 프로듀서는 토픽에 메시지를 발행할 수 있습니다. 발행된 메시지는 브로커라고 불리는 서버 집합에 저장됩니다. 컨슈머는 브로커에 있는 토픽을 하나 이상 구독할 수 있으며, 브로커로부터 데이터를 풀링하여 구독한 메시지를 소비할 수 있습니다.

Messaging is conceptually simple, and we have tried to make the Kafka API equally simple to reflect this. Instead of showing the exact API, we present some sample code to show how the API is used. The sample code of the producer is given below. A message is defined to contain just a payload of bytes. A user can choose her favorite serialization method to encode a message. For efficiency, the producer can send a set of messages in a single publish request.

메시징은 개념적으로 간단하기 때문에, 우리는 이를 반영해 Kafka API도 가능한 간단하게 만들려고 노력했습니다. API가 어떻게 사용되는지 보여주기 위해 정확한 API를 보여주는 대신, 샘플 코드를 소개합니다. 프로듀서의 샘플 코드는 아래와 같습니다. 메시지는 바이트의 페이로드만 포함하도록 정의됩니다. 사용자는 메시지를 인코딩하기 위해 선호하는 직렬화 방법을 선택할 수 있습니다. 효율성을 위해, 프로듀서는 하나의 발행 요청에 메시지들의 집합을 보내는 것도 가능합니다.

Sample producer code:

producer = new Producer(…); message = new Message("test message str".getBytes()); set = new MessageSet(message); producer.send("topic1", set);

To subscribe to a topic, a consumer first creates one or more message streams for the topic. The messages published to that topic will be evenly distributed into these sub-streams. The details about how Kafka distributes the messages are described later in Section 3.2. Each message stream provides an iterator interface over the continual stream of messages being produced. The consumer then iterates over every message in the stream and processes the payload of the message. Unlike traditional iterators, the message stream iterator never terminates. If there are currently no more messages to consume, the iterator blocks until new messages are published to the topic. We support both the point-topoint delivery model in which multiple consumers jointly consume a single copy of all messages in a topic, as well as the publish/subscribe model in which multiple consumers each retrieve its own copy of a topic.

토픽을 구독하려면, 컨슈머는 먼저 토픽에 대해 하나 이상의 메시지 스트림을 생성합니다. 해당 토픽에 발행된 메시지는 이러한 하위 스트림에 균등하게 분배됩니다. Kafka가 메시지를 어떻게 분배하는지에 대한 세부 사항은 3.2절에서 설명합니다. 각각의 메시지 스트림은 계속해서 생성되는 메시지 스트림에 대한 반복자 인터페이스를 제공합니다. 컨슈머는 스트림의 모든 메시지를 반복하고, 메시지의 페이로드를 처리합니다. 전통적인 반복자와 달리, 메시지 스트림 반복자는 종료되지 않습니다. 현재 소비할 메시지가 없다면, 반복자는 새로운 메시지가 토픽에 발행될 때까지 블록됩니다. 우리는 여러 컨슈머가 토픽의 모든 메시지의 단일 복사본을 공동으로 소비하는 점대점 전달 모델과, 여러 컨슈머가 각각 토픽의 복사본을 가져오는 발행/구독 모델을 모두 지원합니다.

Sample consumer code:

streams[] = Consumer.createMessageStreams("topic1", 1) for (message : streams[0]) { bytes = message.payload(); // do something with the bytes }

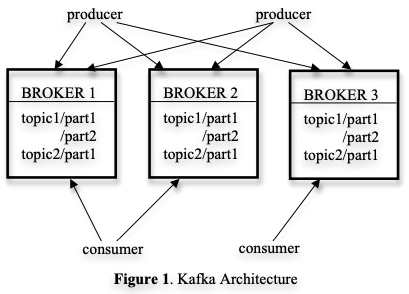

The overall architecture of Kafka is shown in Figure 1. Since Kafka is distributed in nature, an Kafka cluster typically consists of multiple brokers. To balance load, a topic is divided into multiple partitions and each broker stores one or more of those partitions. Multiple producers and consumers can publish and retrieve messages at the same time. In Section 3.1, we describe the layout of a single partition on a broker and a few design choices that we selected to make accessing a partition efficient. In Section 3.2, we describe how the producer and the consumer interact with multiple brokers in a distributed setting. We discuss the delivery guarantees of Kafka in Section 3.3.

Kafka의 전체 아키텍처는 Figure 1에 나와 있습니다. Kafka는 분산 환경이기 때문에, Kafka 클러스터는 일반적으로 여러 브로커들로 구성됩니다. 부하를 균형있게 분산하기 위해, 토픽은 여러 파티션으로 나뉘며, 각 브로커는 그러한 파티션 중 하나 이상을 저장합니다. 여러 프로듀서와 컨슈머가 동시에 메시지를 발행하고 가져올 수 있습니다.

3.1절에서, 브로커의 하나의 파티션에 대한 레이아웃과 파티션에 효율적으로 접근하기 위해 선택한 몇 가지 설계상의 선택에 대해 설명합니다. 그리고 3.2절에서는, 프로듀서와 컨슈머가 분산 환경에서 여러 브로커와 상호작용하는 방법에 대해 설명합니다. 3.3절에서는, Kafka의 전달 보장에 대해 설명합니다.

3.1 Efficiency on a Single Partition

3.1 단일 파티션에서의 효율성

We made a few decisions in Kafka to make the system efficient

Kafka에서는 시스템을 효율적으로 만들기 위해 몇 가지 결정을 내렸습니다.

Simple storage

Simple storage: Kafka has a very simple storage layout. Each partition of a topic corresponds to a logical log. Physically, a log is implemented as a set of segment files of approximately the same size (e.g., 1GB). Every time a producer publishes a message to a partition, the broker simply appends the message to the last segment file. For better performance, we flush the segment files to disk only after a configurable number of messages have been published or a certain amount of time has elapsed. A message is only exposed to the consumers after it is flushed.

간단한 저장소: Kafka는 매우 간단한 저장소 레이아웃을 가지고 있습니다. 토픽의 각 파티션은 논리적인 로그에 해당합니다. 물리적으로, 로그는 대략 같은 크기(예: 1GB)의 세그먼트 파일의 집합으로 구현됩니다. 프로듀서가 파티션에 메시지를 발행할 때마다, 브로커는 단순히 메시지를 마지막 세그먼트 파일에 추가합니다. 더 나은 성능을 위해, 우리는 메시지가 일정한 수가 되었거나 또는 일정한 시간이 지날 때마다 세그먼트 파일을 디스크에 쓰도록 합니다. 메시지는 디스크에 쓰여진(flushed) 후에만 컨슈머에게 노출됩니다.

Unlike typical messaging systems, a message stored in Kafka doesn’t have an explicit message id. Instead, each message is addressed by its logical offset in the log. This avoids the overhead of maintaining auxiliary, seek-intensive random-access index structures that map the message ids to the actual message locations. Note that our message ids are increasing but not consecutive. To compute the id of the next message, we have to add the length of the current message to its id. From now on, we will use message ids and offsets interchangeably.

일반적인 메시징 시스템과는 달리, Kafka에 저장된 메시지에는 명시적인 메시지 id가 없습니다. 그 대신, 각 메시지는 로그에서의 논리적인 오프셋에 의해 주소가 지정됩니다. 이로 인해 메시지 id를 실제 메시지 위치에 매핑하는 '보조적이고 탐색에 집중된 랜덤 액세스 인덱스 구조'를 유지하는 오버헤드를 피할 수 있습니다. 메시지 id는 증가하지만 연속적이지는 않다는 점에 유의하세요. 다음 메시지의 id를 계산하기 위해서는, 현재 메시지의 id에 현재 메시지의 길이를 더해야 합니다. 이제부터, 메시지 id와 오프셋을 서로 바꿔서 사용할 것입니다.

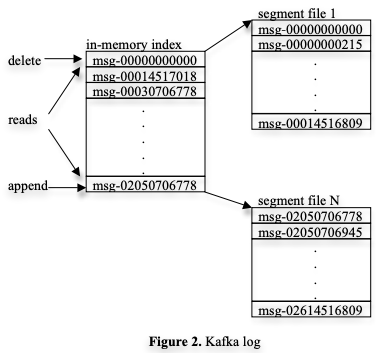

A consumer always consumes messages from a particular partition sequentially. If the consumer acknowledges a particular message offset, it implies that the consumer has received all messages prior to that offset in the partition. Under the covers, the consumer is issuing asynchronous pull requests to the broker to have a buffer of data ready for the application to consume. Each pull request contains the offset of the message from which the consumption begins and an acceptable number of bytes to fetch. Each broker keeps in memory a sorted list of offsets, including the offset of the first message in every segment file. The broker locates the segment file where the requested message resides by searching the offset list, and sends the data back to the consumer. After a consumer receives a message, it computes the offset of the next message to consume and uses it in the next pull request. The layout of an Kafka log and the in-memory index is depicted in Figure 2. Each box shows the offset of a message.

컨슈머는 항상 특정 파티션에서 메시지를 순차적으로 소비합니다. 만약 컨슈머가 특정 메시지 오프셋을 확인했다면, 그 파티션에서 해당 오프셋 이전의 모든 메시지를 받았다는 것을 의미합니다. 내부적으로는, 컨슈머는 브로커에게 비동기 pull 요청을 발행하여, 애플리케이션이 소비할 수 있도록 데이터를 버퍼링합니다. 각 pull 요청에는 소비가 시작되는 메시지의 오프셋과 가져올 수 있는 바이트 수가 포함됩니다. 각 브로커는 메모리에 정렬된 오프셋들의 목록을 유지하며, 이 목록에는 모든 세그먼트 파일의 첫 번째 메시지의 오프셋이 포함됩니다. 브로커는 오프셋 목록을 검색하여 요청된 메시지가 있는 세그먼트 파일을 찾고, 데이터를 컨슈머에게 보냅니다. 컨슈머가 메시지를 받으면, 다음에 소비할 메시지의 오프셋을 계산하고, 다음 pull 요청에 사용합니다. Kafka 로그의 레이아웃과 메모리 내 인덱스는 Figure 2에 나와 있습니다. 각 박스는 메시지의 오프셋을 보여줍니다.

Efficient transfer

Efficient transfer: We are very careful about transferring data in and out of Kafka. Earlier, we have shown that the producer can submit a set of messages in a single send request. Although the end consumer API iterates one message at a time, under the covers, each pull request from a consumer also retrieves multiple messages up to a certain size, typically hundreds of kilobytes.

효율적인 전송: 우리는 Kafka로 데이터를 주고받는 일에 매우 주의를 기울입니다. 위에서 우리는 한 번의 send 요청으로 메시지들의 집합을 제출할 수 있다고 설명했습니다. 최종 컨슈머 API는 한 번에 하나의 메시지를 반복하지만, 내부적으로는 컨슈머의 각 pull 요청도 일정한 크기가 되기까지 여러 메시지를 가져옵니다. 이 크기는 일반적으로 수백 킬로바이트입니다.

Another unconventional choice that we made is to avoid explicitly caching messages in memory at the Kafka layer. Instead, we rely on the underlying file system page cache. This has the main benefit of avoiding double buffering—messages are only cached in the page cache. This has the additional benefit of retaining warm cache even when a broker process is restarted. Since Kafka doesn’t cache messages in process at all, it has very little overhead in garbage collecting its memory, making efficient implementation in a VM-based language feasible. Finally, since both the producer and the consumer access the segment files sequentially, with the consumer often lagging the producer by a small amount, normal operating system caching heuristics are very effective (specifically write-through caching and readahead). We have found that both the production and the consumption have consistent performance linear to the data size, up to many terabytes of data.

우리가 선택한 또다른 일반적이지 않은 선택은 Kafka 레이어에서 메모리에 메시지를 캐싱하지 않는다는 것입니다. 대신, 우리는 기본 파일 시스템 페이지 캐시를 사용합니다. 이로 인해 메시지는 페이지 캐시에만 캐싱되므로, 더블 버퍼링을 피할 수 있습니다. 또한 브로커 프로세스가 재시작되어도 캐시가 유지되는 추가적인 장점이 있습니다.

Kafka가 프로세스에서 전혀 메시지를 캐싱하지 않기 때문에, 메모리의 가비지 컬렉팅 오버헤드가 거의 없습니다. 그러므로 VM 기반 언어에서 효율적인 구현이 가능합니다. 마지막으로, 프로듀서와 컨슈머가 모두 세그먼트 파일에 순차적으로 접근하며, 컨슈머가 프로듀서보다 작은 양만큼 뒤쳐져 있기 때문에, 일반적인 운영체제 캐싱 휴리스틱이 매우 효과적으로 작동합니다(특히 write-through caching과 readahead). 우리는 발행과 소비가 데이터 크기에 대해 선형적으로 일관된 성능을 갖는다는 것을 확인했습니다. 그리고 이는 수 테라바이트의 데이터 규모에서도 적용됩니다.

In addition we optimize the network access for consumers. Kafka is a multi-subscriber system and a single message may be consumed multiple times by different consumer applications. A typical approach to sending bytes from a local file to a remote socket involves the following steps: (1) read data from the storage media to the page cache in an OS, (2) copy data in the page cache to an application buffer, (3) copy application buffer to another kernel buffer, (4) send the kernel buffer to the socket. This includes 4 data copying and 2 system calls. On Linux and other Unix operating systems, there exists a sendfile API [5] that can directly transfer bytes from a file channel to a socket channel. This typically avoids 2 of the copies and 1 system call introduced in steps (2) and (3). Kafka exploits the sendfile API to efficiently deliver bytes in a log segment file from a broker to a consumer.

또한 우리는 컨슈머를 위한 네트워크 접근을 최적화합니다. Kafka는 다중 구독자 시스템이며, 하나의 메시지가 각기 다른 컨슈머 애플리케이션에 의해 여러 번 소비될 수 있습니다. 로컬 파일에서 원격 소켓으로 바이트를 전송하는 일반적인 접근 방식은 다음과 같은 단계를 포함합니다.

- (1) 저장 매체에서 OS 페이지 캐시로 데이터를 읽습니다.

- (2) 페이지 캐시의 데이터를 애플리케이션 버퍼로 복사합니다.

- (3) 애플리케이션 버퍼를 다른 커널 버퍼로 복사합니다.

- (4) 커널 버퍼를 소켓으로 전송합니다.

이로 인해 4번의 데이터 복사와 2번의 시스템 호출이 발생합니다. Linux와 다른 Unix 운영체제에서는 파일 채널에서 소켓 채널로 바이트를 직접 전송할 수 있는 sendfile API가 있습니다. 이것을 사용하면 일반적으로 (2)와 (3) 단계에서 소개된 2개의 복사와 1개의 시스템 호출을 피할 수 있습니다. Kafka는 sendfile API를 사용하여 브로커에서 컨슈머로 로그 세그먼트 파일의 바이트를 효율적으로 전달합니다.

Stateless broker

Stateless broker: Unlike most other messaging systems, in Kafka, the information about how much each consumer has consumed is not maintained by the broker, but by the consumer itself. Such a design reduces a lot of the complexity and the overhead on the broker. However, this makes it tricky to delete a message, since a broker doesn’t know whether all subscribers have consumed the message. Kafka solves this problem by using a simple time-based SLA for the retention policy. A message is automatically deleted if it has been retained in the broker longer than a certain period, typically 7 days. This solution works well in practice. Most consumers, including the offline ones, finish consuming either daily, hourly, or in real-time. The fact that the performance of Kafka doesn’t degrade with a larger data size makes this long retention feasible.

상태 없는 브로커: 대부분의 여타 메시징 시스템들과 달리, Kafka에서는 각 컨슈머가 얼마나 소비했는지에 대한 정보가 브로커가 아니라 컨슈머 자체에 의해 유지됩니다. 이러한 설계로 인해 브로커의 복잡성과 오버헤드가 많이 줄어듭니다. 그러나 이로 인해 모든 구독자가 메시지를 소비했는지를 브로커가 알 수 없으므로, 메시지를 삭제하는 것이 까다로워집니다.

Kafka는 간단한 시간 기반 SLA를 사용하여 보존 정책을 해결합니다. 특정 기간 이상 브로커에 보관된 메시지는 자동으로 삭제됩니다. 이 기간은 일반적으로는 7일 입니다. 이 솔루션은 실제로 잘 작동합니다. 오프라인 컨슈머를 포함한 대부분의 컨슈머는 매일, 매 시간마다, 또는 실시간으로 소비를 완료합니다. Kafka의 성능이 더 큰 데이터 크기에서도 저하되지 않는다는 사실로 인해, 이러한 긴 보존 기간이 가능해집니다.

There is an important side benefit of this design. A consumer can deliberately rewind back to an old offset and re-consume data. This violates the common contract of a queue, but proves to be an essential feature for many consumers. For example, when there is an error in application logic in the consumer, the application can re-play certain messages after the error is fixed. This is particularly important to ETL data loads into our data warehouse or Hadoop system. As another example, the consumed data may be flushed to a persistent store only periodically (e.g, a full-text indexer). If the consumer crashes, the unflushed data is lost. In this case, the consumer can checkpoint the smallest offset of the unflushed messages and re-consume from that offset when it’s restarted. We note that rewinding a consumer is much easier to support in the pull model than the push model.

이 설계에는 중요한 부가적인 장점이 있습니다. 컨슈머는 의도적으로 이전의 오프셋으로 되돌아가서 데이터를 다시 소비할 수 있습니다. 이것은 일반적으로는 queue 데이터 구조의 계약을 위반하지만, 많은 컨슈머에게는 필수적인 기능으로 입증된 것입니다. 예를 들어, 컨슈머의 애플리케이션 로직에 오류가 있을 때, 오류가 수정된 후 특정 메시지를 다시 재생할 수 있습니다. 이것은 특히 데이터 웨어하우스나 하둡 시스템으로의 ETL 데이터 로드에 중요합니다.

또 다른 예를 들어 보자면, 소비된 데이터는 주기적으로만 영구 저장소로 플러시될 수 있습니다(예: 전문 검색 인덱서) . 만약 컨슈머가 크래시되면, 플러시되지 않은 데이터는 손실될 것입니다. 이러한 경우에 컨슈머는 플러시되지 않은 메시지의 가장 작은 오프셋을 체크포인트로 남기고, 재시작할 때 그 오프셋부터 다시 소비할 수 있습니다. 우리는 컨슈머를 되돌리는 것이 pull 모델에서는 push 모델보다 훨씬 더 지원하기 쉽다는 점에 착안했습니다.

3.2 Distributed Coordination

3.2 분산 조정

We now describe how the producers and the consumers behave in a distributed setting. Each producer can publish a message to either a randomly selected partition or a partition semantically determined by a partitioning key and a partitioning function. We will focus on how the consumers interact with the brokers.

이제 분산 환경에서 프로듀서와 컨슈머가 어떻게 동작하는지 설명합니다. 각 프로듀서는 메시지를 '랜덤하게 선택된 파티션' 또는 '파티셔닝 키와 파티션 함수에 의해 의미론적으로 결정된 파티션'에 게시할 수 있습니다. 우리는 컨슈머가 브로커와 어떻게 상호작용하는지에 대해 초점을 맞출 것입니다.

Kafka has the concept of consumer groups. Each consumer group consists of one or more consumers that jointly consume a set of subscribed topics, i.e., each message is delivered to only one of the consumers within the group. Different consumer groups each independently consume the full set of subscribed messages and no coordination is needed across consumer groups. The consumers within the same group can be in different processes or on different machines. Our goal is to divide the messages stored in the brokers evenly among the consumers, without introducing too much coordination overhead.

Kafka는 컨슈머 그룹이라는 개념을 가지고 있습니다. 각각의 컨슈머 그룹은 하나 이상의 컨슈머로 구성되며, 이들은 함께 구독하고 있는 토픽들을 소비합니다. 즉, 각각의 메시지는 그룹 내의 컨슈머 중 하나에게만 전달됩니다. 서로 다른 컨슈머 그룹은 각각 독립적으로 전체 구독된 메시지를 소비하며, 컨슈머 그룹 간에는 조정이 필요하지 않습니다. 같은 그룹 내의 컨슈머는 다른 프로세스 또는 다른 머신에 있을 수 있습니다. 우리의 목표는 브로커에 저장된 메시지를 컨슈머들 사이에 고르게 나누면서도, 이를 위한 조정 오버헤드가 너무 많이 발생하지 않도록 하는 것입니다.

Our first decision is to make a partition within a topic the smallest unit of parallelism. This means that at any given time, all messages from one partition are consumed only by a single consumer within each consumer group. Had we allowed multiple consumers to simultaneously consume a single partition, they would have to coordinate who consumes what messages, which necessitates locking and state maintenance overhead. In contrast, in our design consuming processes only need co-ordinate when the consumers rebalance the load, an infrequent event. In order for the load to be truly balanced, we require many more partitions in a topic than the consumers in each group. We can easily achieve this by over partitioning a topic.

우리의 첫 번째 결정은 토픽 내의 파티션을 병렬 처리의 최소 단위로 만드는 것입니다. 이는 어떤 주어진 시점에도, 각 컨슈머 그룹 내에서 하나의 파티션의 모든 메시지가 하나의 컨슈머에 의해서만 소비된다는 것을 의미합니다. 만약 여러 컨슈머가 동시에 단일 파티션을 소비할 수 있도록 허용했다면, 누가 어떤 메시지를 소비할지를 조정해야 했을 텐데, 이는 락킹(locking)과 상태 유지 오버헤드를 필요로 합니다. 반면, 우리의 설계에서 누가 소비할지를 지정하는 프로세스는 컨슈머가 부하를 재분배하는 것을 조정할 때만 필요한 일입니다. 이는 드문 일입니다. 부하의 균형을 맞추기 위해서는, 각 그룹의 컨슈머보다 토픽의 파티션 수가 훨씬 많아야 합니다. 이는 토픽을 과도하게 파티션화함으로써 쉽게 달성할 수 있습니다.

The second decision that we made is to not have a central “master” node, but instead let consumers coordinate among themselves in a decentralized fashion. Adding a master can complicate the system since we have to further worry about master failures. To facilitate the coordination, we employ a highly available consensus service Zookeeper [10]. Zookeeper has a very simple, file system like API. One can create a path, set the value of a path, read the value of a path, delete a path, and list the children of a path. It does a few more interesting things: (a) one can register a watcher on a path and get notified when the children of a path or the value of a path has changed; (b) a path can be created as ephemeral (as oppose to persistent), which means that if the creating client is gone, the path is automatically removed by the Zookeeper server; (c) zookeeper replicates its data to multiple servers, which makes the data highly reliable and available.

우리의 두 번째 결정은 중앙의 "마스터" 노드를 갖지 않고, 대신 컨슈머들이 분산된 방식으로 서로간에 조정하도록 하는 것입니다. 마스터를 추가하면 마스터 장애에 대한 걱정이 생겨서 시스템이 복잡해질 수 있습니다. 조정을 용이하게 하기 위해서, 우리는 고가용성 합의 서비스인 Zookeeper를 사용합니다.

Zookeeper는 매우 간단한 파일 시스템같은 API를 가지고 있습니다. Zookeeper는 path를 생성하고, path의 값을 설정하고, path의 값을 읽고, path를 삭제하고, path의 자식들을 나열할 수 있습니다. 그리고 몇 가지 더 흥미로운 기능들도 가지고 있습니다.

- (a) path에 watcher를 등록할 수 있고, path의 자식들이나 path의 값이 변경되었을 때 알림을 받을 수 있습니다.

- (b) path를 일시적(ephemeral, persistent와 반대)으로 생성할 수 있습니다. 이는 생성한 클라이언트가 사라지면 Zookeeper 서버가 자동으로 path를 제거한다는 것을 의미합니다.

- (c) zookeeper는 데이터를 여러 서버에 복제하여 데이터가 높은 신뢰성과 가용성을 가지도록 합니다.

Kafka uses Zookeeper for the following tasks: (1) detecting the addition and the removal of brokers and consumers, (2) triggering a rebalance process in each consumer when the above events happen, and (3) maintaining the consumption relationship and keeping track of the consumed offset of each partition. Specifically, when each broker or consumer starts up, it stores its information in a broker or consumer registry in Zookeeper. The broker registry contains the broker’s host name and port, and the set of topics and partitions stored on it. The consumer registry includes the consumer group to which a consumer belongs and the set of topics that it subscribes to. Each consumer group is associated with an ownership registry and an offset registry in Zookeeper. The ownership registry has one path for every subscribed partition and the path value is the id of the consumer currently consuming from this partition (we use the terminology that the consumer owns this partition). The offset registry stores for each subscribed partition, the offset of the last consumed message in the partition.

Kafka는 Zookeeper를 다음과 같은 작업에 사용합니다.

- (1) 브로커와 컨슈머의 추가와 제거를 감지합니다.

- (2) 위의 이벤트가 발생할 때, 각 컨슈머의 재분배 프로세스를 트리거합니다.

- (3) 소비 관계를 유지하고 각 파티션의 소비된 오프셋을 추적합니다.

구체적으로, 각 브로커나 컨슈머가 시작될 때 자신의 정보를 Zookeeper의 브로커 레지스트리나 컨슈머 레지스트리에 저장합니다. 브로커 레지스트리에는 브로커의 호스트 이름과 포트, 그리고 그 브로커에 저장된 토픽과 파티션의 집합이 포함됩니다. 컨슈머 레지스트리에는 컨슈머가 속한 컨슈머 그룹과 그 컨슈머가 구독하는 토픽의 집합이 포함됩니다. 각 컨슈머 그룹은 Zookeeper의 소유권 레지스트리와 오프셋 레지스트리와 연관됩니다. 소유권 레지스트리는 구독한 파티션마다 하나의 path를 가지고 있고, path의 값은 현재 이 파티션을 소비하는 컨슈머의 id입니다. (우리는 이 컨슈머가 이 파티션을 소유한다는 용어를 써서 표현합니다.) 오프셋 레지스트리는 각각의 구독되는 파티션에 대해 마지막으로 소비된 메시지의 오프셋을 저장합니다.

The paths created in Zookeeper are ephemeral for the broker registry, the consumer registry and the ownership registry, and persistent for the offset registry. If a broker fails, all partitions on it are automatically removed from the broker registry. The failure of a consumer causes it to lose its entry in the consumer registry and all partitions that it owns in the ownership registry. Each consumer registers a Zookeeper watcher on both the broker registry and the consumer registry, and will be notified whenever a change in the broker set or the consumer group occurs.

Zookeeper에서 생성된 path는 브로커 레지스트리, 컨슈머 레지스트리, 소유권 레지스트리에 대해서는 일시적이고, 오프셋 레지스트리에 대해서는 영구적입니다. 만약 브로커에 오류가 발생하면, 그 브로커에 있는 모든 파티션은 자동으로 브로커 레지스트리에서 제거됩니다. 그리고 컨슈머에 오류가 발생하면, 컨슈머 레지스트리에서 그 컨슈머의 엔트리가 사라지고, 소유권 레지스트리에서 그 컨슈머가 소유한 모든 파티션을 잃게 됩니다. 각 컨슈머는 브로커 레지스트리와 컨슈머 레지스트리에 대해 Zookeeper watcher를 등록하고, 브로커 집합이나 컨슈머 그룹이 변경될 때마다 알림을 받습니다.

During the initial startup of a consumer or when the consumer is notified about a broker/consumer change through the watcher, the consumer initiates a rebalance process to determine the new subset of partitions that it should consume from. The process is described in Algorithm 1. By reading the broker and the consumer registry from Zookeeper, the consumer first computes the set (PT) of partitions available for each subscribed topic T and the set (CT) of consumers subscribing to T. It then range-partitions PT into |CT| chunks and deterministically picks one chunk to own. For each partition the consumer picks, it writes itself as the new owner of the partition in the ownership registry. Finally, the consumer begins a thread to pull data from each owned partition, starting from the offset stored in the offset registry. As messages get pulled from a partition, the consumer periodically updates the latest consumed offset in the offset registry.

컨슈머가 초기 시작할 때 또는 watcher를 통해 브로커/컨슈머 변경에 대해 알림을 받을 때, 컨슈머는 새로운 파티션 하위 집합을 결정하기 위해 리밸런싱 프로세스를 시작합니다. 이 프로세스는 Algorithm 1에 설명되어 있습니다.

컨슈머는 먼저 Zookeeper에서 브로커와 컨슈머 레지스트리를 읽어서, 각 구독된 토픽 T에 대해 사용 가능한 파티션의 집합 (PT)과 T를 구독하는 컨슈머의 집합 (CT)을 계산합니다. 그런 다음 PT를 |CT|개의 청크로 범위-분할하고, 그 중 하나를 소유하도록 결정합니다. 컨슈머가 선택한 각 파티션에 대해 컨슈머는 소유권 레지스트리에 파티션의 새 소유자로 자신을 기록합니다. 마지막으로 컨슈머는 오프셋 레지스트리에 저장된 오프셋에서 시작하여 각 소유된 파티션에서 데이터를 가져오는 스레드를 시작합니다. 파티션에서 메시지를 가져오면, 컨슈머는 주기적으로 오프셋 레지스트리에 최신으로 소비된 오프셋을 업데이트합니다.

Algorithm 1: rebalance process for consumer \(C_i\) in group G

For each topic T that \(C_i\) subscribes to {

\(\space\) remove partitions owned by Ci from the ownership registry

\(\space\) read the broker and the consumer registries from Zookeeper

\(\space\) compute \(P_T\) = partitions available in all brokers under topic T

\(\space\) compute \(C_T\) = all consumers in G that subscribe to topic T

\(\space\) sort \(P_T\) and \(C_T\)

\(\space\) let j be the index position of \(C_i\) in \(C_T\) and let \(N = | P_T |/| C_T |\)

\(\space\) assign partitions from \(j*N\) to \((j+1)*N - 1\) in \(P_T\) to consumer \(C_i\)

\(\space\) for each assigned partition p {

\(\quad\) set the owner of p to \(C_i\) in the ownership registry

\(\quad\) let \(O_p\) = the offset of partition p stored in the offset registry

\(\quad\) invoke a thread to pull data in partition p from offset \(O_p\)

\(\space\) }

}

알고리즘 1: 그룹 G의 컨슈머 Ci에 대한 리밸런싱 프로세스

for \(C_i\)가 구독하는 각 topic T에 대해 순회한다 {

\(\space\) 소유권 레지스트리에서 \(C_i\)가 소유한 파티션들을 제거한다.

\(\space\) Zookeeper에서 브로커와 컨슈머 레지스트리를 읽는다.

\(\space\) \(P_T\) = 모든 브로커에서 topic T에 대해 사용 가능한 파티션들

\(\space\) \(C_T\) = G에 있는 모든 컨슈머 중 topic T를 구독하는 컨슈머들

\(\space\) \(P_T\)와 \(C_T\)를 정렬한다.

\(\space\) j = \(C_T\)에서 찾은 \(C_i\)의 인덱스 위치.

\(\space\) \(N = | P_T |/| C_T |\).

\(\space\) \(P_T\)에 있는 파티션들 중 \(j*N\)에서 \((j+1)*N - 1\)까지의 파티션을 컨슈머 \(C_i\)에게 할당한다.

\(\space\) for 할당된 각 파티션 p에 대해 순회한다. {

\(\quad\) 소유권 레지스트리에서 파티션 p의 소유자를 \(C_i\)로 설정한다.

\(\quad\) \(O_p\) = 오프셋 레지스트리에 저장된 파티션 p의 오프셋

\(\quad\) 파티션 p에서 오프셋 \(O_p\)부터 데이터를 가져오는 스레드를 실행한다.

\(\space\) }

}

When there are multiple consumers within a group, each of them will be notified of a broker or a consumer change. However, the notification may come at slightly different times at the consumers. So, it is possible that one consumer tries to take ownership of a partition still owned by another consumer. When this happens, the first consumer simply releases all the partitions that it currently owns, waits a bit and retries the rebalance process. In practice, the rebalance process often stabilizes after only a few retries.

그룹 내에 여러 컨슈머가 있을 때, 각 컨슈머는 브로커 또는 컨슈머 변경에 대해 알림을 받습니다. 그러나 알림은 컨슈머들에게 약간 다른 시간에 도착할 수 있습니다. 그래서 한 컨슈머가 다른 컨슈머가 소유한 파티션의 소유권을 취하려고 할 수도 있습니다. 이런 일이 발생하면, 첫 번째 컨슈머는 현재 소유한 모든 파티션을 해제하고 잠시 기다린 다음 리밸런싱 프로세스를 다시 시도합니다. 실제로 리밸런싱 프로세스는 몇 번의 재시도 후에 대부분 안정화됩니다.

When a new consumer group is created, no offsets are available in the offset registry. In this case, the consumers will begin with either the smallest or the largest offset (depending on a configuration) available on each subscribed partition, using an API that we provide on the brokers.

새로운 컨슈머 그룹이 생성되면 오프셋 레지스트리에 오프셋이 없습니다. 이러한 경우, 컨슈머들은 각 구독한 파티션에서 사용 가능한 가장 작은 오프셋 또는 가장 큰 오프셋(구성에 따라 다름)을 사용해 시작하며, 이를 위해 브로커에 제공하는 API를 사용합니다.

3.3 Delivery Guarantees

3.3 전달 보장

In general, Kafka only guarantees at-least-once delivery. Exactlyonce delivery typically requires two-phase commits and is not necessary for our applications. Most of the time, a message is delivered exactly once to each consumer group. However, in the case when a consumer process crashes without a clean shutdown, the consumer process that takes over those partitions owned by the failed consumer may get some duplicate messages that are after the last offset successfully committed to zookeeper. If an application cares about duplicates, it must add its own deduplication logic, either using the offsets that we return to the consumer or some unique key within the message. This is usually a more cost-effective approach than using two-phase commits.

일반적으로 카프카는 적어도 한 번의 전달만을 보장합니다. '정확히 한 번의 전달'은 일반적으로 2단계 커밋을 필요로 하며, 이는 우리의 애플리케이션에는 필수적이지 않습니다. 대부분의 경우, 각 컨슈머 그룹에 메시지가 정확히 한 번 전달됩니다. 그러나 컨슈머 프로세스가 정상적으로 종료되지 않고 크래시가 나는 경우, 실패한 컨슈머가 소유했던 파티션을 이어받는 컨슈머 프로세스는 마지막으로 성공적으로 커밋된 오프셋 이후의 중복 메시지를 얻을 수 있습니다. 애플리케이션에서 중복을 신경쓰는 경우, 컨슈머에게 반환된 오프셋을 사용하거나 메시지 내의 고유 키를 사용하여 자체 중복 제거 로직을 추가해야 합니다. 이는 일반적으로 2단계 커밋을 사용하는 것보다 비용 면에서 효율적인 접근 방식입니다.

Kafka guarantees that messages from a single partition are delivered to a consumer in order. However, there is no guarantee on the ordering of messages coming from different partitions.

Kafka는 단일 파티션에서 온 메시지가 순서대로 컨슈머에게 전달된다는 것을 보장합니다. 그러나 다른 파티션에서 온 메시지의 순서에 대한 보장은 없습니다.

To avoid log corruption, Kafka stores a CRC for each message in the log. If there is any I/O error on the broker, Kafka runs a recovery process to remove those messages with inconsistent CRCs. Having the CRC at the message level also allows us to check network errors after a message is produced or consumed.

로그 손상을 방지하기 위해, Kafka는 각 메시지에 대한 CRC를 저장합니다. 브로커에서 I/O 에러가 발생하면, Kafka는 일관성이 없는 CRC를 가진 메시지들을 제거하는 복구 프로세스를 실행합니다. 메시지 레벨에서 CRC를 갖고 있으므로, 메시지가 생성되거나 소비된 이후에도 네트워크 에러를 확인할 수 있습니다.

If a broker goes down, any message stored on it not yet consumed becomes unavailable. If the storage system on a broker is permanently damaged, any unconsumed message is lost forever. In the future, we plan to add built-in replication in Kafka to redundantly store each message on multiple brokers.

만약 브로커가 다운되면, 브로커에 저장된 아직 소비되지 않은 메시지는 사용할 수 없게 됩니다. 브로커의 저장 시스템에 영구적인 손상이 발생했다면, 소비되지 않은 메시지는 영원히 잃게 됩니다. 앞으로 Kafka에 빌트인 복제(replication) 기능을 추가하여 각 메시지를 여러 브로커에 중복으로 저장할 계획입니다.

4. Kafka Usage at LinkedIn

4. LinkedIn에서 Kafka를 사용하는 방법

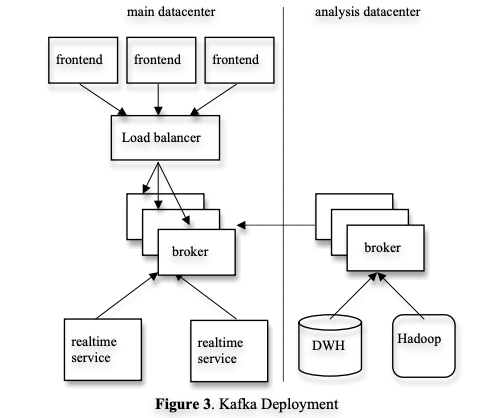

In this section, we describe how we use Kafka at LinkedIn. Figure 3 shows a simplified version of our deployment. We have one Kafka cluster co-located with each datacenter where our userfacing services run. The frontend services generate various kinds of log data and publish it to the local Kafka brokers in batches. We rely on a hardware load-balancer to distribute the publish requests to the set of Kafka brokers evenly. The online consumers of Kafka run in services within the same datacenter.

이 섹션에서는 LinkedIn에서 Kafka를 사용하는 방법에 대해 설명합니다.

Figure 3은 우리의 배포의 단순화된 버전을 보여줍니다.

사용자와 대면하는 서비스가 실행되는 각 데이터 센터에는 하나의 Kafka 클러스터가 있습니다. 프론트엔드 서비스는 다양한 종류의 로그 데이터를 생성하고, 이를 로컬 Kafka 브로커에 배치로 전송합니다. 하드웨어 로드밸런서를 사용하여, Kafka 브로커 집합에 고르게 전송 요청을 분배합니다. Kafka의 온라인 컨슈머는 동일한 데이터 센터 내의 서비스에서 실행됩니다.

We also deploy a cluster of Kafka in a separate datacenter for offline analysis, located geographically close to our Hadoop cluster and other data warehouse infrastructure. This instance of Kafka runs a set of embedded consumers to pull data from the Kafka instances in the live datacenters. We then run data load jobs to pull data from this replica cluster of Kafka into Hadoop and our data warehouse, where we run various reporting jobs and analytical process on the data. We also use this Kafka cluster for prototyping and have the ability to run simple scripts against the raw event streams for ad hoc querying. Without too much tuning, the end-to-end latency for the complete pipeline is about 10 seconds on average, good enough for our requirements.

우리는 또한 오프라인 분석을 위해 별도의 데이터 센터에 Kafka 클러스터를 배포합니다. 이 클러스터는 Hadoop 클러스터와 기타 데이터 웨어하우스 인프라에 지리적으로 가까이 있습니다. 이 Kafka 인스턴스는 실시간 데이터 센터의 Kafka 인스턴스에서 데이터를 가져오기 위해 내장된 컨슈머 집합을 실행합니다. 그런 다음, 이 '복제 Kafka 클러스터에서 데이터를 가져오기 위한 데이터 로드 작업'을 Hadoop 및 데이터 웨어하우스에서 실행하고, 이 데이터를 통해 다양한 리포팅 작업과 분석 프로세스를 실행합니다. 또한, 이 Kafka 클러스터를 프로토타이핑에 사용하고, ad hoc 쿼리를 위해 원시 이벤트 스트림에 대해 간단한 스크립트를 실행할 수 있는 기능도 갖추고 있습니다. 너무 많은 튜닝을 하지 않아도 전체 파이프라인의 엔드 투 엔드 지연 시간은 평균적으로 10초 정도로, 우리의 요구 사항에 충분합니다.

Currently, Kafka accumulates hundreds of gigabytes of data and close to a billion messages per day, which we expect will grow significantly as we finish converting legacy systems to take advantage of Kafka. More types of messages will be added in the future. The rebalance process is able to automatically redirect the consumption when the operation staffs start or stop brokers for software or hardware maintenance.

현재 Kafka는 하루에 수백 기가 바이트의 데이터와 10억 건에 가까운 메시지를 누적하고 있습니다. 이는 Kafka를 활용하도록 기존의 시스템을 전환하는 것이 완료되면 급격히 증가할 것으로 예상합니다. 앞으로 더 많은 종류의 메시지가 추가될 것입니다. 운영 직원이 소프트웨어 또는 하드웨어 유지 보수를 위해 브로커를 시작하거나 중지할 때, 리밸런스 프로세스가 자동으로 소비를 리디렉션할 수 있습니다.

Our tracking also includes an auditing system to verify that there is no data loss along the whole pipeline. To facilitate that, each message carries the timestamp and the server name when they are generated. We instrument each producer such that it periodically generates a monitoring event, which records the number of messages published by that producer for each topic within a fixed time window. The producer publishes the monitoring events to Kafka in a separate topic. The consumers can then count the number of messages that they have received from a given topic and validate those counts with the monitoring events to validate the correctness of data.

전체 파이프라인에서 데이터 손실이 없는지 확인하기 위한 감사(auditing) 시스템도 포함되어 있습니다. 이를 위해, 각 메시지는 생성될 때 타임스탬프와 서버 이름을 포함합니다. 우리는 각 프로듀서를 측정해서, 고정된 시간 윈도우 내에서 해당 생산자가 각 토픽에 게시한 메시지 수를 기록하는 모니터링 이벤트를 주기적으로 생성하도록 합니다. 프로듀서는 별도의 토픽에 모니터링 이벤트를 발행합니다. 그런 다음, 컨슈머는 특정 토픽에서 수신한 메시지 수를 계산하고, 모니터링 이벤트와 비교하여 데이터의 정확성을 확인할 수 있습니다.

Loading into the Hadoop cluster is accomplished by implementing a special Kafka input format that allows MapReduce jobs to directly read data from Kafka. A MapReduce job loads the raw data and then groups and compresses it for efficient processing in the future. The stateless broker and client-side storage of message offsets again come into play here, allowing the MapReduce task management (which allows tasks to fail and be restarted) to handle the data load in a natural way without duplicating or losing messages in the event of a task restart. Both data and offsets are stored in HDFS only on the successful completion of the job.

Hadoop 클러스터에 데이터를 로드하는 것은 Kafka에서 데이터를 직접 읽을 수 있는 MapReduce 작업에다가 특별한 Kafka 입력 형식을 구현하는 방식으로 수행됩니다. MapReduce 작업은 원시 데이터를 로드한 다음, 그룹화하고 압축하여 미래에 효율적인 처리를 가능하게 해둡니다. '상태없는 브로커와 클라이언트 측 메시지 오프셋 저장'은 여기에서도 작동합니다. 작업 재시작 시 메시지를 중복하거나 손실하지 않고, MapReduce 작업 관리(작업이 실패해도 재시작되도록 허용)가 데이터 로드를 자연스럽게 처리할 수 있도록 해줍니다. 작업이 성공적으로 완료되면 데이터와 오프셋은 HDFS에 저장됩니다.

We chose to use Avro [2] as our serialization protocol since it is efficient and supports schema evolution. For each message, we store the id of its Avro schema and the serialized bytes in the payload. This schema allows us to enforce a contract to ensure compatibility between data producers and consumers. We use a lightweight schema registry service to map the schema id to the actual schema. When a consumer gets a message, it looks up in the schema registry to retrieve the schema, which is used to decode the bytes into an object (this lookup need only be done once per schema, since the values are immutable).

우리는 직렬화 프로토콜로 Avro를 선택했는데, Avro는 효율적이고 스키마의 변화를 지원하기 때문입니다. 각 메시지에는 Avro 스키마의 id와 페이로드의 직렬화된 바이트를 저장합니다. 이런 스키마를 사용하면 데이터 프로듀서와 컨슈머 사이의 호환성을 보장하기 위한 계약을 강제할 수 있습니다. 우리는 스키마 id를 실제 스키마에 매핑하는 가벼운 스키마 레지스트리 서비스를 사용합니다. 컨슈머가 메시지를 하나 받으면, 컨슈머는 스키마 레지스트리에서 스키마를 검색해서 바이트를 객체로 디코딩하는데 사용합니다(불변값을 사용하기 때문에 이 검색은 스키마당 한 번씩만 수행하면 됩니다).

5. Experimental Results

5. 실험 결과

We conducted an experimental study, comparing the performance of Kafka with Apache ActiveMQ v5.4 [1], a popular open-source implementation of JMS, and RabbitMQ v2.4 [16], a message system known for its performance. We used ActiveMQ’s default persistent message store KahaDB. Although not presented here, we also tested an alternative AMQ message store and found its performance very similar to that of KahaDB. Whenever possible, we tried to use comparable settings in all systems.

우리는 Kafka의 성능을 'Apache ActiveMQ v5.4', '인기 있는 오픈 소스 JMS 구현체', '뛰어난 성능으로 유명한 메시지 시스템 RabbitMQ v2.4' 와 비교하는 실험적 연구를 수행했습니다. 우리는 ActiveMQ의 기본 메시지 저장소인 KahaDB를 사용했습니다. 여기서는 표시하지 않았지만, 우리는 대안으로 AMQ 메시지 저장소도 테스트했고 그 성능이 KahaDB와 매우 유사하다는 것도 알게 되었습니다. 가능한 한, 우리는 모든 시스템에서 비슷한 설정을 사용하려고 노력했습니다.

We ran our experiments on 2 Linux machines, each with 8 2GHz cores, 16GB of memory, 6 disks with RAID 10. The two machines are connected with a 1Gb network link. One of the machines was used as the broker and the other machine was used as the producer or the consumer.

우리는 각각 8개의 2GHz 코어, 16GB 메모리, RAID 10을 사용하는 6개의 디스크를 가진 2개의 리눅스 머신에서 실험을 수행했습니다. 두 머신은 1Gb 네트워크 링크로 연결되어 있습니다. 한 대의 머신은 브로커로 사용되고, 다른 머신은 프로듀서 또는 컨슈머로 사용되었습니다.

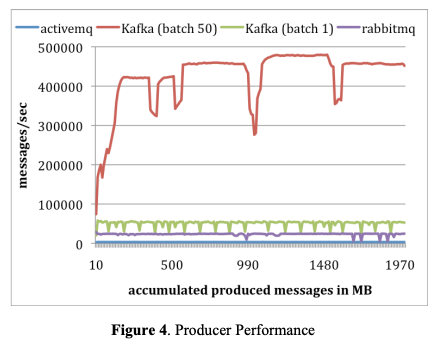

Producer Test

Producer Test: We configured the broker in all systems to asynchronously flush messages to its persistence store. For each system, we ran a single producer to publish a total of 10 million messages, each of 200 bytes. We configured the Kafka producer to send messages in batches of size 1 and 50. ActiveMQ and RabbitMQ don’t seem to have an easy way to batch messages and we assume that it used a batch size of 1. The results are shown in Figure 4. The x-axis represents the amount of data sent to the broker over time in MB, and the y-axis corresponds to the producer throughput in messages per second. On average, Kafka can publish messages at the rate of 50,000 and 400,000 messages per second for batch size of 1 and 50, respectively. These numbers are orders of magnitude higher than that of ActiveMQ, and at least 2 times higher than RabbitMQ.

프로듀서 테스트: 우리는 모든 시스템의 브로커를 비동기적으로 메시지를 영속성 저장소에 쓰도록 설정했습니다. 각 시스템에 대해, 우리는 총 천만 개의 메시지를 발행하는 한 개의 프로듀서를 실행했고, 각 메시지 사이즈는 200바이트였습니다. Kafka 프로듀서는 메시지를 1개와 50개 규모로 배치로 보내도록 설정했습니다. ActiveMQ와 RabbitMQ는 메시지를 배치로 보내는 쉬운 방법이 없는 것으로 보여서, 우리는 배치 사이즈를 1개로 사용한다고 가정했습니다.

결과는 Figure 4에 나와있습니다.

x축은 시간의 흐름에 따라 브로커에 전송된 데이터 양을 MB로 나타내고, y축은 프로듀서의 처리량을 초당 메시지 수로 표시합니다. 평균적으로, Kafka는 배치 사이즈가 1일 때 초당 5만 개의 메시지를, 배치 사이즈가 50일 때 초당 40만 개의 메시지를 발행할 수 있습니다. 이 숫자는 ActiveMQ보다 훨씬 높고, RabbitMQ보다 적어도 2배 이상 높습니다.

There are a few reasons why Kafka performed much better. First, the Kafka producer currently doesn’t wait for acknowledgements from the broker and sends messages as faster as the broker can handle. This significantly increased the throughput of the publisher. With a batch size of 50, a single Kafka producer almost saturated the 1Gb link between the producer and the broker. This is a valid optimization for the log aggregation case, as data must be sent asynchronously to avoid introducing any latency into the live serving of traffic. We note that without acknowledging the producer, there is no guarantee that every published message is actually received by the broker. For many types of log data, it is desirable to trade durability for throughput, as long as the number of dropped messages is relatively small. However, we do plan to address the durability issue for more critical data in the future.

Kafka가 훨씬 더 좋은 성능을 보인 이유는 다음과 같습니다.

첫째, Kafka 프로듀서는 현재 브로커로부터 확인 응답을 기다리지 않고, 브로커가 처리할 수 있는 최대한 빠르게 메시지를 보냅니다. 이는 퍼블리셔의 처리량을 크게 증가시켰습니다. 배치 사이즈가 50일 때, 한 개의 Kafka 프로듀서는 프로듀서와 브로커 사이의 1Gb 링크를 거의 포화 상태로 만들었습니다. 이것은 로그 집계의 경우에는 유효한 최적화이며, 실시간 트래픽 처리에 지연을 발생시키지 않기 위해 데이터를 비동기적으로 전송해야 합니다.

프로듀서의 확인 응답을 받지 않는다면, 발행된 모든 메시지가 실제로 브로커에 전달되는 것을 보장할 수 없다는 점에 주의해야 합니다. 많은 종류의 로그 데이터의 경우, 손실된 메시지의 수가 상대적으로 적은 편이라면 처리율을 위해 내구성을 희생하는 것이 바람직합니다. 그러나, 우리는 앞으로 더 중요한 데이터에 대한 내구성 문제를 해결할 계획이 있습니다.

Second, Kafka has a more efficient storage format. On average, each message had an overhead of 9 bytes in Kafka, versus 144 bytes in ActiveMQ. This means that ActiveMQ was using 70% more space than Kafka to store the same set of 10 million messages. One overhead in ActiveMQ came from the heavy message header, required by JMS. Another overhead was the cost of maintaining various indexing structures. We observed that one of the busiest threads in ActiveMQ spent most of its time accessing a B-Tree to maintain message metadata and state. Finally, batching greatly improved the throughput by amortizing the RPC overhead. In Kafka, a batch size of 50 messages improved the throughput by almost an order of magnitude.

둘째, Kafka는 더 효율적인 저장 포맷을 가지고 있습니다. 평균적으로, Kafka에서 각 메시지의 오버헤드는 9 바이트였고, ActiveMQ에서는 144 바이트였습니다. 이는 ActiveMQ가 똑같은 1000만 개의 메시지 집합을 저장하는 데 있어 Kafka보다 70% 더 많은 공간을 사용하고 있다는 것을 의미합니다. ActiveMQ의 오버헤드 중 하나는, JMS에서 요구하는 무거운 메시지 헤더입니다. 또 다른 오버헤드는 다양한 인덱싱 구조를 유지하는 데 드는 비용입니다. 우리는 관찰 결과 ActiveMQ에서 가장 바쁜 스레드 중 하나가 메시지 메타데이터와 메시지의 상태를 관리하기 위해 B-Tree에 접근하는 데 거의 모든 시간을 소비한다는 것을 알게 됐습니다.

그리고 마지막으로, 배치는 RPC 오버헤드를 분산시켜 처리량을 크게 향상시켰습니다. Kafka에서 배치 사이즈가 50인 경우, 처리율을 거의 한 자릿수 향상시켰습니다.

Consumer Test

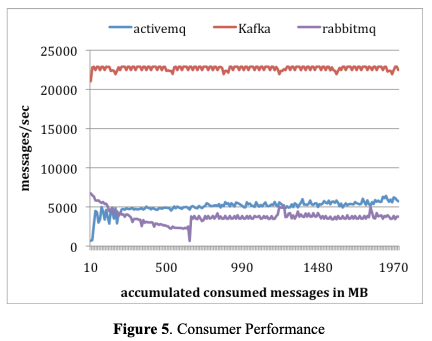

Consumer Test: In the second experiment, we tested the performance of the consumer. Again, for all systems, we used a single consumer to retrieve a total of 10 millions messages. We configured all systems so that each pull request should prefetch approximately the same amount data—up to 1000 messages or about 200KB. For both ActiveMQ and RabbitMQ, we set the consumer acknowledge mode to be automatic. Since all messages fit in memory, all systems were serving data from the page cache of the underlying file system or some in-memory buffers. The results are presented in Figure 5.

컨슈머 테스트: 두 번째 실험에서는 컨슈머의 성능을 테스트했습니다. 앞에서와 같이, 모든 시스템에서 한 개의 컨슈머를 사용해 총 천만 개의 메시지를 가져오도록 했습니다. 우리가 구성한 모든 시스템은 각각의 풀 요청이 최대 1000개의 메시지 또는 약 200KB의 데이터를 가져오도록 했습니다. ActiveMQ와 RabbitMQ는 컨슈머 확인 모드를 자동으로 설정했습니다. 모든 메시지가 메모리에 들어갈 만큼 작기 때문에, 모든 시스템은 기본 파일 시스템의 페이지 캐시 또는 메모리 버퍼에서 데이터를 제공했습니다. 결과는 Figure 5에 나와 있습니다.

On average, Kafka consumed 22,000 messages per second, more than 4 times that of ActiveMQ and RabbitMQ. We can think of several reasons. First, since Kafka has a more efficient storage format, fewer bytes were transferred from the broker to the consumer in Kafka. Second, the broker in both ActiveMQ and RabbitMQ had to maintain the delivery state of every message. We observed that one of the ActiveMQ threads was busy writing KahaDB pages to disks during this test. In contrast, there were no disk write activities on the Kafka broker. Finally, by using the sendfile API, Kafka reduces the transmission overhead.

Kafka는 평균적으로 초당 22,000개의 메시지를 소비하여, 이는 ActiveMQ와 RabbitMQ보다 4배 이상 더 많은 것입니다. 우리는 그 이유를 다음과 같이 생각했습니다.

첫째, Kafka가 더 효율적인 저장 포맷을 가지고 있기 때문에, Kafka에서 브로커에서 컨슈머로 전송되는 바이트 수가 적었습니다.

둘째, ActiveMQ와 RabbitMQ의 브로커는 모든 메시지의 전달 상태를 유지해야 했습니다. 우리는 이 테스트 중에 ActiveMQ의 스레드 중 하나가 KahaDB 페이지를 디스크에 쓰는 작업을 하느라 바쁘다는 것을 관찰했습니다. 반면, Kafka 브로커에서는 디스크 쓰기 활동이 없었습니다.

마지막으로, Kafka는 sendfile API를 사용하여 전송 오버헤드를 줄입니다.

We close the section by noting that the purpose of the experiment is not to show that other messaging systems are inferior to Kafka. After all, both ActiveMQ and RabbitMQ have more features than Kafka. The main point is to illustrate the potential performance gain that can be achieved by a specialized system.

우리는 이 섹션을 마무리하면서, 이 실험의 목적이 다른 메시징 시스템이 Kafka보다 더 나쁜 것을 보여주는 것이 아니라는 점을 언급하고자 합니다. 종합적으로 봤을 때, ActiveMQ와 RabbitMQ는 Kafka보다 더 많은 기능을 가지고 있습니다. 주요 포인트는 특수화된 시스템으로 달성할 수 있는 잠재적인 성능 향상을 보여주는 것이었습니다.

6. Conclusion and Future Works

We present a novel system called Kafka for processing huge volume of log data streams. Like a messaging system, Kafka employs a pull-based consumption model that allows an application to consume data at its own rate and rewind the consumption whenever needed. By focusing on log processing applications, Kafka achieves much higher throughput than conventional messaging systems. It also provides integrated distributed support and can scale out. We have been using Kafka successfully at LinkedIn for both offline and online applications.

우리는 로그 데이터 스트림의 대량 처리를 위한 새로운 시스템인 Kafka를 소개했습니다. 메시징 시스템처럼, Kafka는 애플리케이션이 자신의 속도로 데이터를 소비하고 필요할 때 소비를 되감을 수 있는 pull 기반의 소비 모델을 사용합니다. 로그 처리 애플리케이션에 집중함으로써, Kafka는 전통적인 메시징 시스템보다 훨씬 높은 처리량을 달성합니다. 또한, Kafka는 통합된 분산 지원을 제공하며 scale out도 가능합니다. 우리는 LinkedIn에서 오프라인과 온라인 애플리케이션 모두에 대해 Kafka를 성공적으로 사용하고 있습니다.

There are a number of directions that we’d like to pursue in the future. First, we plan to add built-in replication of messages across multiple brokers to allow durability and data availability guarantees even in the case of unrecoverable machine failures. We’d like to support both asynchronous and synchronous replication models to allow some tradeoff between producer latency and the strength of the guarantees provided. An application can choose the right level of redundancy based on its requirement on durability, availability and throughput. Second, we want to add some stream processing capability in Kafka. After retrieving messages from Kafka, real time applications often perform similar operations such as window-based counting and joining each message with records in a secondary store or with messages in another stream. At the lowest level this is supported by semantically partitioning messages on the join key during publishing so that all messages sent with a particular key go to the same partition and hence arrive at a single consumer process. This provides the foundation for processing distributed streams across a cluster of consumer machines. On top of this we feel a library of helpful stream utilities, such as different windowing functions or join techniques will be beneficial to this kind of applications.

우리가 앞으로 추진하고자 하는 방향은 다음과 같습니다.

첫째, 여러 브로커간에 메시지를 복제하는 빌트인 기능을 추가하여, 회복할 수 없는 머신 장애가 발생하는 경우에도 데이터 내구성과 가용성을 보장하고자 합니다. 비동기식 및 동기식 복제 모델을 모두 지원하여 프로듀서의 지연 시간과 제공되는 보장 강도 사이의 균형을 맞출 수 있도록 하고자 합니다. 애플리케이션은 내구성, 가용성 및 처리율에 따라 적절한 중복 수준을 선택할 수 있습니다.

둘째, 우리는 Kafka에 스트림 처리 기능을 추가하고자 합니다. Kafka에서 메시지를 가져온 후, 실시간 애플리케이션은 종종 윈도우 기반 카운팅과 같은 유사한 작업을 수행하며, 각 메시지를 두 번째 저장소 또는 다른 스트림의 메시지와 결합합니다. 이 방법은 가장 낮은 레벨에서 지원되며, 특정 키로 전송된 모든 메시지가 동일한 파티션으로 전송되고, 따라서 단일 컨슈머 프로세스로 도착하도록 공급자가 조인 키를 기준으로 메시지를 파티션으로 나누는 것을 의미합니다. 이를 통해 컨슈머 머신의 클러스터 전체에서 분산된 스트림을 처리하는 기반을 제공하게 됩니다. 이를 기반으로 다양한 윈도우 기능이나 조인 기술과 같은 유용한 스트림 유틸리티 라이브러리가 이러한 애플리케이션에 유용할 것이라고 생각합니다.

7. REFERENCES

- [1] http://activemq.apache.org/

- [2] http://avro.apache.org/

- [3] Cloudera’s Flume, https://github.com/cloudera/flume

- [4] http://developer.yahoo.com/blogs/hadoop/posts/2010/06/enabling_hadoop_batch_processi_1/

- [5] Efficient data transfer through zero copy: https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/linux/library/jzerocopy/

- [6] Facebook’s Scribe, http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=32008268919

- [7] IBM Websphere MQ: http://www01.ibm.com/software/integration/wmq/

- [8] http://hadoop.apache.org/

- [9] http://hadoop.apache.org/hdfs/

- [10] http://hadoop.apache.org/zookeeper/

- [11] http://www.slideshare.net/cloudera/hw09-hadoop-baseddata-mining-platform-for-the-telecom-industry

- [12] http://www.slideshare.net/prasadc/hive-percona-2009

- [13] https://issues.apache.org/jira/browse/ZOOKEEPER-775

- [14] JAVA Message Service: http://download.oracle.com/javaee/1.3/jms/tutorial/1_3_1-fcs/doc/jms_tutorialTOC.html.

- [15] Oracle Enterprise Messaging Service: http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/middleware/ias/index093455.html

- [16] http://www.rabbitmq.com/

- [17] TIBCO Enterprise Message Service: http://www.tibco.com/products/soa/messaging/

- [18] Kafka, http://sna-projects.com/kafka/