(번역) The Feel of Java

- 원문: 1997-06 The Feel of Java by James Gosling

- 의역 많으니 원문도 같이 읽어보세요.

The Feel of Java

Java is a blue collar language. It’s not PhD thesis material but a language for a job. Java feels very familiar to many different programmers because we preferred tried-and-tested things.

Java는 블루칼라 언어입니다. 박사 논문을 위한 도구가 아니라 직업에 필요한 언어입니다. 우리는 시행착오를 거쳐 검증된 것을 선호합니다. 그래서 우리가 만든 Java는 여러 프로그래머들에게 매우 친숙하게 느껴질 것입니다.

머리말

Java evolved out of a Sun research project started six years ago to look into distributed control of consumer electronics devices. It was not an academic research project studying programming languages: Doing language research was actively an antigoal. For the first three years, I worked on the language and the runtime, and everybody else in the group worked on a variety of different prototype applications, the things that were really the heart of the project. So the drive for changes came from the people who were actually using it and saying “do this, do this, do this.”

6년 전, Sun에서는 가전제품 분산 제어 시스템을 연구하기 위한 프로젝트 하나가 시작됐습니다. Java는 그 프로젝트에서 발전한 언어입니다. 그 프로젝트는 프로그래밍 언어 연구라는 학술적인 목표를 갖고 있지 않았습니다. 완전히 다른 목표를 갖는 프로젝트였죠. 나는 처음 3년간은 언어와 런타임을 연구했습니다. 그리고 그룹의 다른 모든 사람들은 프로젝트의 핵심인 다양한 프로토타입 애플리케이션에 대한 작업을 수행했습니다. 즉, Java 언어가 탄생하게 된 변화는 실제로 그것을 사용하고 "이거 하고, 이것도 해보자, 저것도 할까"라고 말하며 일하던 사람들에게서 나온 것입니다.

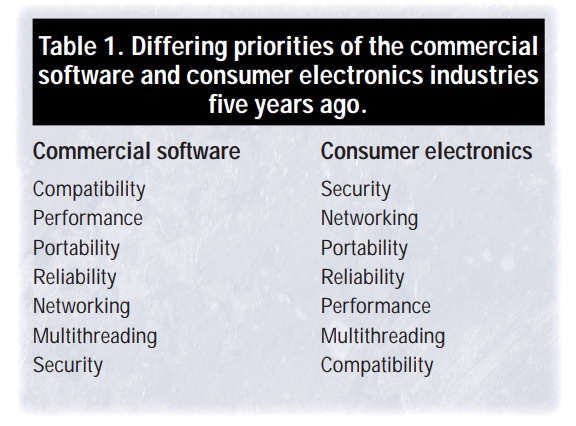

Probably the most important thing I learned in talking to the folks building TVs and VCRs was that their priorities were quite different from ours in the computer industry. Whereas five years ago our mantra was compatibility, the consumer electronics industry considered secure networking, portability, and cost far more important. And when compatibility did become an issue, they limited notions of compatibility to well-defined interfaces— unlike the computer industry where the most ubiquitous interface around, namely DOS, is full of secret back doors that make life extremely difficult.

TV, VCR을 만드는 사람들과 대화하며 내가 배운 가장 중요한 것은 컴퓨터 산업에 속해 있는 우리의 우선순위와 그들의 우선순위가 매우 다르다는 사실이었습니다. 5년 전 기준으로 우리의 핵심 목표는 호환성이었습니다. 그러나 가전제품 업계에서는 안전한 네트워킹, 이식성, 그리고 가격을 훨씬 더 중요하게 여기고 있더군요. 만약 호환성에 문제가 생기면 그들은 인터페이스를 잘 정의해 호환성을 제한하는 방식을 사용하고 있었습니다. 이런 방식은 당시의 컴퓨터 산업에서 가장 널리 사용되던 인터페이스인 DOS가 삶을 어렵게 만드는 수많은 비밀 백도어로 돌아가고 있던 것과는 상반되는 방식이었습니다.

I’ve listed the differing priorities for the commercial software and consumer electronics industries in Table 1. One interesting phenomenon that has occurred over the past five years is that consumer electronics concerns have become mainstream software concerns as the market for software in the home has grown.

표 1은 상용 소프트웨어 업계와 가전제품 업계의 우선순위를 나열해 본 것입니다. 지난 5년 동안 발생한 흥미로운 현상 하나는 가정용 소프트웨어 시장이 성장하면서, 전자제품이 일반 소프트웨어 시장에서 더 중요해졌다는 것입니다.

The buzzwords that have been applied to Java derive directly from this context. In the consumer electronics world, you connect your VCR to a television, your telephone to a network. And the consumer electronics industry wants to make these kinds of networked appliances even more pervasive.

Java의 화두(buzzwords)들은 이러한 컨텍스트에서 도출됐습니다. 전자제품을 다룰 때를 떠올려 봅시다. 우리들은 VCR은 TV에 연결하고 전화기는 네트워크에 연결하죠. 전자제품 업계는 이렇게 서로 연결되는 종류의 네트워크 가전제품을 더 폭넓게 보급하고 싶어합니다.

Architecture neutrality is another issue. In the consumer electronics business, there are dozens of different CPU types and good reasons for all of them in their individual contexts. But developing software for a dozen different platforms just doesn’t scale, and it was this desire for architecture neutrality that broke the C++ mold—not so much C++ the language, but the standard way people built C++ compilers.

이를 위해 아키텍처 중립성도 중요한 이슈가 됩니다. 가전제품 비즈니스에는 다양한 CPU 타입이 수십 가지가 있는데, 그 각각이 각자의 컨텍스트에서 합리적인 근거를 갖고 있습니다. 하지만 소프트웨어 개발은 이렇게 각자 다른 여러 플랫폼에 쉽게 적용할 수 있는 작업이 아니죠. C++라는 틀(C++ 언어가 아니라 사람들이 C++ 컴파일러를 빌드하는 표준 방식)을 깨게 된 것은 아키텍처 중립성에 대한 이러한 필요가 있었기 때문입니다.

BLUE COLLAR LANGUAGE

Java is a blue collar language. It’s not PhD thesis material but a language for a job. Java feels very familiar to many different programmers because I had a very strong tendency to prefer things that had been used a lot over things that just sounded like a good idea. And so Java ended up as this fusion of four different kinds of programming.

Java는 블루칼라 언어입니다. 박사 논문을 위한 도구가 아니라 직업에 필요한 언어입니다. 나는 좋은 이론들보다 실제로 사람들에게 사용된 것을 선호합니다. 그래서 Java는 여러 프로그래머들에게 매우 친숙하게 느껴질 것입니다. Java는 검증된 4가지 종류의 프로그래밍 형태를 융합시킨 결과이기도 합니다.

- It has an object-oriented flavor that derives from a number of languages—Simula, C/C++, Objective C, Cedar/Mesa, Modula, and Smalltalk.

- Another one of my favorite areas is numeric programming. One of the things that’s different about Java is that we say what 2 + 2 means. When C came out there were so many different ways of computing 2 + 2 that you couldn’t lay down any kind of rule. But today, the IEEE 754 standard for floating-point arithmetic has won, and the world owes William Kahan and the other folks who worked on it a real debt, because it removes much of the complexity and clutter in numerical programming.

- Java also has a systems programming flavor inherited from C that has proven useful over the years.

- But the one way in which Java is unique is its distributed nature—it feels like there aren’t boundaries between machines. People can have pieces of behavior squirt back and forth across the network, picked up here, landed over there. And they just don’t care. The network, by and large, starts to behave like a sea of computation on which you can go rafting.

- Java는 Simula, C/C++, Objective C, Cedar/Mesa, Modula, Smalltalk 같은 여러 언어에서 파생된 객체지향적 특징이 있습니다.

- 내가 좋아하는 특징 하나는 숫자 프로그래밍입니다.

Java가 다른 언어와 다른 점은,

2 + 2가 무엇을 의미하는지 분명히 말해준다는 것입니다. C 언어에서는2 + 2를 계산하는 방법이 너무 다양해서 어떤 규칙도 확정해서 적용할 수가 없었습니다. 하지만 오늘날엔 부동소수점 연산을 위한 IEEE 754 표준이 채택되었으므로 숫자 프로그래밍의 복잡성과 혼란함이 상당히 제거되었죠. William Kahan과 그 연구진들에게 빚을 지고 있다고 할 수 있습니다. - Java는 오랫동안 유용성이 입증된 C 언어로부터 물려받은 시스템 프로그래밍 형태를 갖추고 있습니다.

- Java는 분산 특성을 갖고 있습니다. 즉, 여러 머신들 사이에 경계가 없는 것처럼 느껴진다는 것입니다. 사람들은 Java를 통해 네트워크를 가로질러 다양한 활동을 할 수 있습니다. 이곳에서 자료를 얻고, 저곳에서 착륙하고 그럴 수 있죠. 이런 작업들이 손쉽게 이루어지기에 네트워크는 여러분이 래프팅을 할 수 있는 계산의 바다처럼 작동하게 됩니다.

Distributed objects on the Web

In this particular environment, one of the key design requirements was to create quanta of behavior that could be shipped from place to place. Oddly enough, classes provide a nice encapsulation boundary for defining what one of these quantum particles is.

이러한 환경에서 비롯된 핵심 설계 요구사항은, 이곳저곳으로 이동할 수 있는 행위의 퀀텀을 만드는 것이었습니다. 클래스는 훌륭한 캡슐화 경제를 제공하므로, 이러한 퀀텀 파티클을 정의할 수 있게 해줍니다.

We also wanted to keep these quanta of behavior separate from data, which at the time was a real departure. General Magic was doing a very similar thing, except it was putting the code and the data together. In some cases this has a real advantage, but what if you’re shipping around JPEG images? You end up in an untenable situation if every JPEG image has to have its own JPEG decompressor: You load a page with 20 images and end up with 20 JPEG decompressors at 100 Kbytes each.

우리는 또한 행위들을 데이터와 분리하고 싶었는데, General Magic은 코드와 데이터를 함께 몰아놓는다는 것을 제외하고는 이와 매우 유사했습니다. 이렇게 모아놓으면 경우에 따라 장점이 있기는 합니다. 그러나 만약 JPEG 이미지를 여러개 전송한다고 생각해 봅시다. 모든 JPEG 이미지가 각각의 JPEG 디코더를 가지고 있다면 어떻게 될까요? 20개의 이미지가 포함된 페이지를 로드하고 나면 각각 100 Kbyte 용량을 가진 JPEG 디코더가 20개나 생성될 것입니다.

So we worked hard to make sure that data and implementation were separate, but that the data could have tags that say, “I’m a bag of bytes that’s understood by this type.” And if the client doesn’t understand the component’s data type, it would be able to turn around and say, “Gee Mr. Server, do you have the implementation for this particular type?” and reach out across the Internet, grab the implementation, and do some checking to make sure that it won’t turn the disk drive into a puddle of ash.

따라서 우리는 데이터와 구현을 최대한 분리하려 노력했고, 데이터는 "저는 이 타입으로 해석될 수 있는 byte 덩어리입니다" 라는 태그를 가지고 있게 됐습니다. 그리고 만약 클라이언트가 컴포넌트의 데이터 타입을 인식하지 못한다면, 컴포넌트의 구현을 얻기 위해 인터넷을 가로질러 서버를 불러서 "저기 서버 선생님, 이 타입에 대한 구현체를 갖고 계신가요?"라고 물어볼 수 있습니다.

Thin clients

You can think of this as the client learning something. It now understands a new data type that it didn’t understand before, and it obtained that knowledge from some remote repository. You can start building systems that are much more lean, that feel as though there’s this core that understands the basic business of the application.

이런 방식을 클라이언트가 무언가를 배운다는 것으로도 생각할 수 있습니다. 클라이언트는 예전에 알지 못했던 새로운 데이터 타입을 원격 저장소에서 얻어 이해하게 되는 것입니다. 이제 여러분은 애플리케이션의 기본적인 비즈니스를 이해하는 코어가 있다고 전제하고 훨씬 더 lean 한 시스템 구축을 시작할 수 있습니다.

A Web browser is a good example. It’s a simple loop—a set of interfaces to networking standards, document format standards, image format standards, and so on. And other components can plug into this browser until you have this huge brick of code around which you wrap a big steel band. That’s your application, and it does everything. But what’s lost in this pile of support code is the essence of a Web browser.

웹 브라우저가 이런 방식의 좋은 예시입니다. 웹 브라우저는 네트워킹 표준, 문서 형식 표준, 이미지 형식 표준 등의 인터페이스를 갖고 있는 단순한 반복문입니다. 그리고 다른 컴포넌트를 브라우저에 연결하는 것도 가능하며, 큰 코드 블럭을 둘러싼 다른 컴포넌트들도 있습니다. 이런 방식으로 웹 브라우저는 바로 여러분의 애플리케이션이 되며 여러분이 원하는 모든 작업을 수행하게 되는데, 그 결과 웹 브라우저는 본질을 잃는다고도 할 수 있습니다.

Similarly, the support code itself tends to lose its boundaries because people start getting sloppy. They start saying, “Well gee, there’s this global variable over there that HTML was using, but I could use that creatively with my HTTP driver.” It always bites you in the end, even though short term it feels good. With Java, we tended to do things that promoted up-front pain and long-term health, one of those funny religious principles.

이와 비슷하게 지원 코드 자체도 사람들이 엉성해지면서 그 경계를 잃는 경향이 있습니다. 그들은 "HTML이 저쪽에서 사용하고 있었던 전역 변수가 있긴 해요, 하지만 나는 HTTP 드라이버를 써서 그 전역변수를 창의적으로 사용할 수 있습니다" 이렇게 하면 당장은 기분이 좋겠지만, 결국엔 자신의 발등을 찍게 됩니다. Java와 함께 하면서, 우리는 재미있는 종교적 원칙 중 하나인 향상된 up-front pain과 long-term health를 지원하는 방식으로 일을 해왔습니다.

Architecture neutral

Much of Java was driven by the Internet, and there’s a series of deductive steps that follow from that starting point. The Internet has a diverse population, some companies’ aspirations to the contrary. If you need to avoid doing different versions for different platforms, then you need some way of distributing software that is architecturally neutral. C, by and large, has been very portable, apart from a few gotchas like what does int mean. So we pushed for a uniform feeling and a deterministic semantics, so that you know what 2 + 2 means and what kind of evaluation order you have.

Java는 많은 부분이 인터넷을 의식하고 개발됐습니다.

그리고 그러한 시작점부터 이어져 내려오는 연역적 단계들이 있습니다.

인터넷에는 다양한 사람들의 욕구가 있는데, 몇몇 기업들이 하고자 하는 바는 이와 반대되기도 합니다.

만약 각각의 플랫폼마다 다른 버전을 적용하는 것이 싫다면, 구조적으로 중립적인 소프트웨어 배포 방법이 필요하게 된 것입니다.

C 언어의 경우 매우 이식성이 뛰어나지만, int의 의미 같은 몇 가지 이상한 문제들이 있죠.

그래서 우리는 일관적인 느낌과 결정적인 의미를 전달할 수 있도록 작업했습니다.

예를 들어 2 + 2가 무엇을 의미하는지, 어떤 평가 우선순위를 갖고 있는지를 어느 플랫폼에서도 알 수 있게끔.

JAVA VIRTUAL MACHINE

At the same time, I made the mistake of going to school too long and actually getting a PhD, so I couldn’t avoid doing a little bit of theoretical stuff. And besides, when you have people like Bill Joy (Sun cofounder and VP for Research) and Guy Steele (Sun Microsystems Distinguished Engineer) peering over your shoulder and wagging their fingers at you, things become a lot cleaner than the initial hacks one is tempted to commit in the spirit of expediency. And the theoretical work that went into Java really did add a lot of cohesiveness and cleanliness to it. Most of those things are under the covers in the way the virtual machine works. Things like the verifier, which is this minidataflow program prover that determines whether or not programs follow the game rules. But by and large, this kind of innovation was relatively rare in Java.

한편, 나는 학교를 너무 오래 다니다 보니 진짜로 박사학위를 받는 실수를 저지른 사람이어서 그만 이론적인 작업을 조금 해버리고 말았습니다. Bill Joy(Sun의 공동창업자 겸 연구부문 부사장)라던가 Guy Steele(Sun Microsystems의 뛰어난 기술자)같은 사람들이 어깨 너머로 훈수를 두고 있다고 생각해 보세요. 상쾌한 마음으로 해킹을 하게 됩니다. 그래서 Java에 적용한 이론적인 작업들은 상당히 응집력이 있고 깨끗한 편입니다. 이런 것들 대부분은 가상 머신이 작동하는 방식에 내부적으로 숨겨져 있습니다. 가령 verifier 같은 미니 데이터 플로우 프로그램은 프로그램이 게임 규칙에 따라 제대로 작동하는지를 확인합니다. 하지만 이런 종류의 혁신적인 작업들은 Java에서는 비교적 드문 편이었습니다.

We use a very old technique where the compiler generates some bytecoded instructions for this abstract virtual machine that’s based largely on work from Smalltalk and Pascal-P machines. I put a lot of effort into making it very easy to interpret and verify bytecode before it was compiled into machine code, using both an interpreter and a machine code generator to make sure that generating machine code was pretty straightforward.

우리는 컴파일러가 추상적 가상 머신에서 가동할 바이트 코드 명령을 생성하는 방식의 오래된 기술을 사용합니다. Smalltalk와 Pascal-P 머신의 작업들에서 사용되던 것이죠. 나는 바이트코드가 기계어로 컴파일되기 전에 바이트코드를 쉽게 해석하고 검증할 수 있도록 많은 노력을 했습니다. 그리고 기계어 코드 생성이 간단한지 확인하기 위해 인터프리터와 기계어 생성기를 사용했습니다.

Compile-time checking

The Java compiler does a lot of compile-time checking that people aren’t used to, and some have complained about the compiler’s attitude, that it essentially has no warnings. For example, “used-before-set” is a fatal compilation error rather than just a warning. These may feel like restrictions, but it’s rare that the compiler gives an error message without a very good reason. In all cases, we would try something and see how many bugs came out of the woodwork.

Java 컴파일러는 컴파일 타임에 그동안 사람들이 크게 신경쓰지 않았던 종류의 다양한 검사를 합니다. 그래서 몇몇 사람들은 경고가 없는(no warnings) 컴파일러의 행동에 대해 불평했습니다. 예를 들어 "used-before-set"의 경우 치명적인 컴파일 에러가 되며, 단순 경고만 보여주고 지나가지 않았기 때문입니다. 이런 것들이 제약으로 느껴질 수 있겠지만, 컴파일러가 에러 메시지를 표시하는 것은 대부분 나름의 이유가 있기 때문입니다. 모든 경우에 대해, 우리는 다양한 시도를 했을 때 우리의 작업물에서 얼마나 많은 버그가 기어나오는지를 확인할 수 있었죠.

One of the interesting cases was name hiding. It’s pretty traditional in languages to allow nested scopes to have names that are the same as names in the outer scope, and that’s certainly the way it was in Java early on. But people had nasty experiences where they forgot they named a variable i in an outer scope, then declared an i in an inner scope thinking they were referring to the outer scope, and it would get caught by the inner scope. So we disallowed name hiding, and it was amazing how many errors were eliminated. Granted, it is sometimes an aggravation, but statistically speaking, people get burned a lot by doing that, and we’re trying to avoid people getting burned.

흥미로운 사례들 중 하나는 이름 숨기기였습니다.

중첩된 스코프에서 바깥쪽 스코프에 있는 이름과 같은 이름을 가질 수 있도록 허용하는 것은 전통적인 프로그래밍 언어 방식이며, 초기 Java에서도 그러했습니다.

그러나 사람들은 이와 관련된 불쾌한 경험을 겪곤 했습니다. 바깥쪽 스코프에서 변수 i를 선언한 것을 잊고 안쪽 스코프에서 다시 i를 선언하면서 바깥쪽 i를 참조한다고 생각했던 것입니다. 물론 그렇게 하면 안쪽 스코프에 걸리게 되어 있죠.

그래서 우리는 이름 숨기기를 허용하지 않았습니다. 그러자 놀랍게도 대단히 많은 에러가 사라졌습니다.

물론 이런 제약이 좋지 않은 것일 수도 있겠지만, 어떤 활동 때문에 통계적으로 많은 사람들이 화상을 입곤 한다면 우리는 사람들이 화상을 입지 않도록 노력할 것입니다.

Garbage collection

Another thing that’s essential for reliability, oddly enough, is garbage collection. Garbage collection has a long and honorable history, starting out in the Lisp community, but it acquired a bad reputation because it tended to take more time than was necessary. Garbage collection gained the reputation of being used by lazy programmers who didn’t want to call malloc and free. But in actual fact, there are a lot of other ways to justify it. And to my mind, one of the ways that works well when you’re talking to some hard-nosed engineer is that it helps make systems more reliable. You don’t have memory leaks or dangling pointers, and you cut your software maintenance budget in half by not having to chase them. With Java, you never need to worry about pointers off into hyperspace, pointers to one element beyond the end of your array.

이상하게 들릴 수 있겠지만, 신뢰성을 확보하기 위해 필수적인 것은 쓰레기 수집입니다. 가비지 컬렉션은 Lisp 커뮤니티에서 시작된 오래되고 훌륭한 역사를 갖고 있습니다. 다만 시간이 너무 오래 걸린다는 문제가 있어 좋지 못한 평가를 받고 있었죠. 그러나 가비지 컬렉터의 사용을 정당화하는 방법은 많이 있습니다. 내 생각에, 냉철한 엔지니어와 대화할 때 그들을 설득하는 방법 중 하나는 시스템을 더 신뢰할 수 있게 만드는 데 도움이 된다고 말하는 것입니다. 메모리 누수나 댕글링 포인터가 사라지게 되어 추적하지 않아도 된다고 생각해 보세요. 소프트웨어 유지보수 예산도 절반으로 줄일 수 있을 겁니다. Java를 사용하면 배열의 끝을 넘어서는 포인터를 걱정하지 않아도 됩니다.

Pointer restrictions

This also relates to restrictions on pointers and pointer arithmetic, which can lead to interface integrity problems. We in the engineering world have become accustomed to taking back doors into an object’s private space to solve problems in the short term. In C, there’s a standard cliché I’ve used frequently—

((int *) p) [n]—where you take some pointer, cast it to a pointer or to an integer, subscript it, and are then able to get anything as anything. The world is your oyster.

이 문제는 인터페이스 무결성 문제들과 관련된 포인터 및 포인터 연산에 대한 제한과 관련이 있습니다.

엔지니어링 업계에서 일하고 있는 우리는 문제를 빠르게 해결하기 위해 각 객체의 private 영역으로 백도어를 가져오는 방식으로 일을 처리하곤 했습니다.

가령, C 언어에서 나는 ((int *) p) [n]같은 흔한 코드를 자주 사용했습니다.

포인터를 가져다가 포인터나 integer로 캐스팅하고 첨자를 붙이면 어떤 값이든 마음대로 가져올 수 있죠.

세상 모든 것이 내 마음대로인 것입니다.

But long term, this practice always bites you. It creates a tremendous versioning problem, and systems become incredibly fragile. Having one little private variable can make the whole system fall apart. If you look at what often happens in commercial systems, you’ll find they end up not using object-oriented programming because of these back doors. They end up doing it in a way that hides all the stuff, so that it’s much more obscure.

하지만 장기적인 관점에서 보면 이런 습관은 발등을 찍게 됩니다. 이런 방식은 버전 문제가 발생할 수 있으며 시스템 또한 엄청나게 취약해집니다. 심각하게는 private 변수 하나로 전체 시스템이 붕괴할 수도 있는 것입니다. 상용 시스템에서 이런 문제는 자주 일어나는 편이며, 이런 백도어를 방지하기 위해 객체지향 프로그래밍이 선택되지 않기도 합니다. 결국 모든 것을 숨기는 방향으로 작업이 진행되며 결과적으로 모든 것이 모호해지는 결과를 낳게 됩니다.

Exception handling

The exception model that we picked up pretty much straight out of Modula 3 has been, I think, a real success. Initially, I was somewhat anxious about it, because the whole notion of having a rigorous proof that an exception will get tossed can be something of a burden. But in the end, that is a good burden to have. When you aren’t testing for exceptions, the code is going to break at some time in any real environment where surprising things always happen. Ariane 5 provides a vivid lesson on how important exception handling is.

우리가 선택한 Modula 3의 예외 모델은 실제로 성공적이었다고 생각합니다. 처음에는 예외가 던져질 것이라는 증거가 있다는 개념이 부담스럽지 않을까 생각했습니다. 하지만 그건 좋은 의미의 부담스러움이었습니다. 만약 예외를 테스트하지 않는다면 실제 환경에서 예상하지 못한 상황이 되었을 때 코드는 깨지게 될 것입니다. 예외 처리가 얼마나 중요한지에 대에서는 Ariane 5로부터 교훈을 얻은 바 있습니다.

Although exception handling makes Java feel somewhat clumsy because it forces you to think about something you’d rather ignore, your applications are ultimately much more solid and reliable.

무시하고 싶은 것을 억지로 생각하게 만드는 Java의 예외 처리 방식 때문에 Java가 좀 서투른 언어처럼 느껴질 수 있습니다. 하지만 그로 인해 Java로 개발한 애플리케이션들은 실제로 더 견고할 것이고, 더 신뢰할 수 있을 것입니다.

OBJECT-ORIENTED EXTENSIBILITY

One of the things about Java that I pushed on pretty hard was allowing for future change. Much of that comes from Java’s Lisp-like late binding, where methods are looked up on the fly at the very end. But there’s a lot of optimization that gets done to rewrite the instructions so that method calls are fast and the various code generators turn them into the obvious threeinstruction sequence.

Java에 대해 내가 열심히 밀어붙인 것 하나는 미래의 변화를 허용하는 것이었습니다. 그리고 그것과 관련된 많은 부분이 Lisp과 같은 방식의 Java의 late binding에 적용되었습니다. 이러한 late binding으로 인해 메소드들은 실제로 실행되기 직전에 탐색됩니다. 여기에는 상당한 양의 최적화가 적용되어서, 메소드 호출은 빠르게 작동하며 코드 생성기가 이를 명시적인 3개의 명령어 시퀀스로 변환합니다.

Thus, you can add methods almost fearlessly and can add and remove private variables with total impunity. You have to make sure of a few things—for example, that you don’t remove methods that aren’t being used, or if you want to remove or change them, you at least leave another method in there whose type signature is the same. As long as you practice this relatively simple discipline, you can change classes pretty readily without having to worry about how this breaks all of your subclasses and the applications based on them.

따라서 여러분은 메소드를 추가로 정의하거나, private 변수를 추가하고 제거할 때 걱정하지 않아도 됩니다. 물론 사용하지 않는 메소드를 제거하지 않거나, 제거/변경하는 등의 작업을 할 때 적어도 타입 시그니처가 같은 메소드를 남겨둬야 한다는 것은 인지하고 있어야 합니다. 이런 간단한 원칙들을 연습한다면, 모든 서브 클래스와 그런 것들을 토대로 굴러가는 애플리케이션들이 망가질 것을 걱정하지 않고 클래스를 쉽게 변경할 수 있을 것입니다.

What I found most interesting in watching people use Java was that they used it in a way similar to rapid prototyping languages. They just whacked something together. I was initially surprised by that, because Java is a very strongly typed system, and dynamic typing is often considered one of the real requirements of a rapid prototyping environment. But after watching people for a while and doing it myself and thinking “Why does this feel this way to me,” I decided that probably the most important thing was that in a typical rapid prototyping language like Smalltalk, you find out about it fast when something goes wrong. There aren’t these mysterious memory smashes. Java does a pretty good job of avoiding situations where mysterious alpha particles come in from hyperspace and blow up your system, where you spend four days to discover that you had a for-loop clearing an array that went one element too far, and where that fact isn’t discovered until thousands of instructions later when some other memory block is being accessed.

내가 사람들이 Java를 사용하는 것을 관찰해 오면서 느낀 흥미로운 점 한 가지는, 사람들이 빠른 프로토타입 언어와 비슷한 방식으로 Java를 사용했다는 것입니다. 사람들은 바로바로 무언가를 때려넣었습니다. 동적 타이핑은 신속한 프로토타이핑 환경의 요구 사항으로 요구되는 것이었던 반면, Java는 매우 강력한 타입 시스템이었으므로 나는 처음에는 꽤 놀랍게 느꼈습니다. 한동안 사람들을 관찰하고 나서 나는 "이 방법이 왜 놀라운 느낌이 드는 걸까?"같은 생각을 했습니다. 나는 아마 Smalltalk 같은 빠른 프로토타이핑 언어에서는 뭔가 잘못됐을 때 빨리 발견할 수 있는 것이 중요하다는 생각을 하게 됐습니다. Java는 원인을 알 수 없는 미스테리한 메모리 충돌이 없습니다. Java는 초공간에서 알 수 없는 알파 입자가 들어와 시스템을 날려버리는 상황을 아주 잘 방지합니다. 배열을 지우는 for 루프를 돌렸지만 원소 하나가 너무 멀리 떨어져 있었다는 사실을 발견할 때까지 나흘이나 걸린다던가 하는 상황 말이죠. 사실 이런 경우는 수천개의 명령이 실행되어 다른 메모리 블록에 엑세스하기 전까지는 발견하지 못합니다.

Dynamic linking

Another important aspect of Java is that it’s dynamic. Dynamic linking—where classes come in and have their links snapped very late—lets you adapt to change. Change not only in the versioning problem from one generation of software to the next, but also in the sense of being able to load handlers for new data types. It lets the system defer a lot of decisions—principally object layout—to the runtime.

Java의 또다른 중요한 측면은 동적으로 작동한다는 것입니다. Dynamic linking(클래스를 추가하면, 늦게 링크되는 방식)은 여러분이 변화에 적응할 수 있도록 도와줍니다. 변화는 단순히 버전 문제 이상을 의미합니다. 새로운 데이터 타입에 대한 처리기를 로드할 수 있다는 의미도 갖고 있습니다. 이 방법을 통해 시스템은 많은 결정(주로 객체 레이아웃)을 런타임에 지연 적용할 수 있습니다.

We had a longstanding debate, particularly with people from the Objective C crowd, about factories versus constructors. A factory is a static method on a type—that is, you would say

type.newrather thannew Type. I was not totally persuaded by the factory argument because there was always the problem of who, in the end, creates the object. So Java stayed with the C++ way of sayingnew Type.

우리는 특히 Objective C 쪽의 사람들과 팩토리와 생성자에 대해 오랫동안 논쟁을 벌어기도 했습니다.

팩토리는 특정 타입에 대한 정적 메소드입니다. new Type 보다 type.new를 사용하는 방식이죠.

이 방식은 최종적으로는 누군가가 객체를 생성해야 한다는 문제가 있었으므로 나는 팩토리 방식에 수긍하지 못했습니다.

그래서 Java는 new Type 처럼 표현하는 C++의 방식을 고수하게 되었습니다.

But factories are used as a style in places where you don’t know exactly what you want or if you need a new object. If you want a font, for example, you don’t necessarily want to create it and might prefer to look it up. Java’s dynamic behavior is often fed by this style of using static factory methods to allocate objects rather than call the constructor directly.

하지만, 팩토리는 우리가 어떤 것을 생성해야 할 지 정확히 알지 못하는 상황을 해결하기 위한 스타일이기도 합니다. 예를 들어 폰트를 생성해야 한다면 폰트를 직접 만들지 않고 이미 만들어져 있는 것을 찾아보는 것이 좋겠죠. Java의 동적인 작동 방식은 종종 생성자를 직접 호출하는 것이 아니라 정적 팩토리 메소드를 사용하여 객체를 할당하는, 이런 스타일을 통해 제공되기도 합니다.

One way this is used is in this short cliché of doing new on a string name, where you start by calling a static method on a class called

forName, which takes the string as a parameter and gives you a class object that happens to have that name. Where this becomes interesting is when the string parameter toforNameis something that you compute by concatenating strings together. You use a method on a class object calledmakeInstance, which calls the default constructor:Class c = Class.forName("foo."+x); Thing b = (Thing) c.makeInstance();

문자열로 주어진 클래스 이름에 대해 new를 실행해주는 짧고 흔한 방식이 바로 이 기법을 사용하는 방법 중 하나라 할 수 있습니다.

이 방법은 클래스의 forName이라 부르는 정적 메소드를 호출하며, 문자열을 파라미터로 받아 해당 이름을 가진 클래스 객체를 돌려주게 됩니다.

여기에서 흥미로운 점은 forName에 제공한 문자열 파라미터가 여러 문자열을 연결해 만들 수 있다는 것입니다.

그리고 그렇게 얻은 클래스 객체의 makeInstance 메소드를 호출하면 기본 생성자가 호출되게 됩니다.

These two things together interact with these objects in Java called class loaders, which are responsible for taking a class name and finding an actual class implementation for it. This is the central cliché for achieving this quanta of behavior where we take the MIME type, for instance, do a little bit of string mushing to turn the MIME type into a class name, and say

Class.forName, which causes all sorts of HTTP searches to happen. And then magically you’ve got a handler for that type that’s been installed dynamically.

이 방법을 사용하면 이 객체들은 클래스 로더라고 부르는 것과 상호작용을 하게 됩니다. 클래스 로더는 클래스 이름에 해당하는 실제 클래스 구현을 찾는 것을 담당합니다.

이것은 MIME 타입을 얻기 위해 MIME 타입을 클래스 이름으로 변환하기 위한 것과 흡사한 핵심적인 클리셰입니다.

예를 들어, MIME 타입을 클래스 이름으로 바꾸기 위해서 문자열을 좀 조작하고, Class.forName이라 불러서 HTTP 검색이 발생하게 하는 거죠.

그러면 여러분은 마치 마법같이 동적으로 설치된 해당 타입에 대한 핸들러를 갖게 되는 것입니다.

Another stylized way we use this is for adapters. Adapters are interfaces that are designed for achieving portability. Say you have an interface to some networking abstraction or file system, and you want to provide both a consistent superclass with a consistent interface and an appropriate subclass that is dependent upon the actual operating system you’re using. Adapter objects are often looked up by using a factory rather than a normal constructor. We then use the previous cliché fed by a property inquiry like

system.getPropertyofos.name, as shown in Figure 1, which returns a string like Solaris or Win32. If you’re trying to find an implementation of this abstract class Spam and you have a SpamSolaris, a SpamWin32, and a SpamMac class, you can go through this sequence to obtain the appropriate “spamming” class for your machine. And it ends up being completely portable.System.getProperty("os.name") abstract class Spam {...} class SpamSolaris extends Spam {...} class SpamWin32 extends Spam {...} Class c = Class.forName("Spam" + System.getProperty("os.name"));

이와 관련된 다른 기법은 어댑터에 대한 것입니다.

어댑터는 이식성을 위해 설계된 인터페이스라 할 수 있습니다.

네트워킹 추상화나 파일 시스템을 표현하는 인터페이스가 하나 있다고 가정해 봅시다.

그리고 이 둘을 모두 지원하는 실제 운영 체제에 종속되는 적당한 하위 클래스를 제공하기 바란다고 생각해 봅시다.

어댑터 객체는 주로 생성자가 아닌 팩토리를 사용하여 찾습니다.

그런 다음, 코드 1과 같이 os.name의 system.getProperty와 같은 속성 조회 클리셰를 사용합니다.

이렇게 하면 Solaris나 Win32 같은 문자열을 리턴하게 되죠.

만약 여러분이 abstract class Spam의 구현체를 찾으려 할 때 SpamSolaris, SpamWin32, SpamMac 같은 클래스가 있다면, 이 방법으로 운영 체제에 맞는 적당한 하위 클래스를 찾을 수 있습니다.

이를 통해 이식성이 확보됩니다.

PERFORMANCE

We were working on a prototype just-in-time compiler from the very beginning, as I felt strongly that Java had to feel fast. I wanted something comparable to C in performance. This feeling came from watching what people did with previous scripting languages I had written, where they always pushed them way beyond what I expected.

우리는 처음부터 just-in-time 컴파일러를 만들고 있었는데, Java가 빠르게 작동해야 한다고 강력하게 생각하고 있었기 때문입니다. 나는 성능 측면에서는 Java가 C에 맞먹을 수 있기를 바랐습니다. 이런 생각은 내가 예전에 만들었던 스크립트 언어들을 사람들이 어떻게 사용하는지를 보았기 때문입니다. 사람들은 항상 내가 생각했던 것 이상의 성능을 바라고 있었습니다.

Much of Java’s semantics and that of the virtual machine were driven by a couple of canonical examples. Namely, I wanted to get

a = b + cto be one instruction, andp.mof something to be about three instructions. It currently tends to be four or five, which is still a pretty small number. That goal pretty much dictated that the system be statically typed. Many languages infer a fair amount of this type information or they’ll compile it, assume a type, and then do checks, but that adds a huge amount of complexity. Strong typing simplifies the translation process tremendously and picks up a lot of programming errors as well.

Java와 가상 머신의 시맨틱 대부분은 몇 가지 표준적인 예제에 의해 도출된 것입니다.

나는 a = b + c가 하나의 명령이 되길 원했고, p.m의 경우 3개의 명령이 되길 바랐습니다.

지금은 4~5개 정도 되는데, 이것도 꽤 작은 수이긴 합니다.

아무튼 이 목표로 인해 시스템은 정적 타입을 제공하는 방향을 갖게 됐습니다.

많은 언어들이 상당한 양의 타입 정보에 대해 추론하거나, 컴파일하고 타입을 추론하고, 타입을 체크하는데, 이는 상당히 복잡도가 높은 일입니다.

강력한 타이핑을 사용하면 이러한 번역 프로세스를 상당히 단순화하며, 많은 프로그래밍 에러도 잡아낼 수 있습니다.

Java 1.0 was tuned far more for portability than for performance, but I think it still performed reasonably well. Today, there are a number of JIT compilers on the market that are not quite up there with C but are getting awfully close. It’s pretty interesting to have a language that has a scripting feel without the usual scripting language performance. Furthermore, rewriting the interpreter in assembly would give us at least a factor of three speedup, and actual machine code generators would give us a factor of 10 or 20. There is now enough demand for Java to justify all that platform-dependent work, if only because it makes other people’s jobs easier.

Java 1.0은 성능보다 이식성을 위해 조정된 버전이었지만, 그럼에도 그 정도면 합리적인 성능이었다고 생각합니다. 오늘날 업계에서는 C 언어 만큼은 아니지만 그에 거의 근접한 JIT 컴파일러가 많이 있습니다. 스크립트 언어 느낌이 나면서 그와 동시에 스크립트 언어를 넘어선 성능의 언어를 사용하는 것은 흥미로운 일입니다. 또한, 어셈블리어를 사용해 인터프리터를 재작성하면 속도가 적어도 3배 빨라지고, 실제 기계어 생성기는 10~20배 정도 빨라질 것입니다. 이제 Java는 플랫폼 의존적인 모든 작업을 정당화할 수 있으며 사람들의 일자리를 더 쉽게 만들어 주게 되었습니다. 따라서 충분한 수요를 갖게 되었습니다.

Another important thing about Java is its rich class library. Java itself, as a language, is pretty simple, as are most languages. The real action is in the libraries, and we tried hard to have a fairly large class library straight out of the box. That was pretty easy for us because we wrote buckets of code for these prototype consumer electronics applications. This gives the environment a very rich feeling, although it’s clear we have a long way to go. This is probably where we’re working the hardest right now.

Java의 또다른 중요한 점은 풍부한 클래스 라이브러리입니다. Java 자체는 다른 언어들과 마찬가지로 꽤 단순한 프로그래밍 언어입니다. 실제 작업은 라이브러리에 있습니다. 우리는 Java가 상당한 규모의 클래스 라이브러리를 갖게 하기 위해 열심히 노력했습니다. 이런 작업은 꽤 쉬운 편이었는데, 우리가 프로토타입 가전제품 애플리케이션용 코드 버킷들을 작성해 둔 적이 있었기 때문입니다. 아직 갈 길이 멀기는 하지만, 이런 작업들로 인해 꽤 풍부한 느낌이 드는 환경을 만들 수 있었습니다. 아마 지금이 우리가 가장 열심히 일하고 있는 지점일 것입니다.

마무리

So, how does Java feel? Java feels playful and flexible. You can build things with it that are themselves flexible. Java feels deterministic. You feel like it’s going to do what you ask it to do. It feels fairly nonthreatening in that you can just try something and you’ll quickly get an error message if it’s crazy. It feels pretty rich. We tried hard to have a fairly large class library straight out of the box. By and large, it feels like you can just sit down and write code.

자, Java의 느낌이 어떻습니까? Java는 재미있고 유연한 느낌이 있습니다. 여러분은 Java를 사용해 유연한 것들을 만들 수 있습니다. Java는 결정적인 느낌도 갖습니다. 여러분이 생각한대로 작동할 것 같은 느낌도 있을 것입니다. 그저 뭔가를 시도할 수 있으므로 무섭지도 않습니다. 뭔가 잘못되면 빠르게 에러 메시지를 받을 수도 있습니다. Java는 풍부한 느낌도 듭니다. 우리는 뚜껑을 열자마자 상당히 큰 클래스 라이브러리가 튀어나오도록 하기 위해 열심히 노력했습니다. 여러분은 그냥 자리에 앉아서 코딩만 하시면 됩니다.

참고문헌

- 1997-06 The Feel of Java by James Gosling